Investigation Reveals FDA Was ‘Lax’ In Approving Blood Thinner Pradaxa

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration was “lax” and “permissive” in its approval of a widely prescribed blood thinner known as Pradaxa, according to an independent investigation of the agency’s review process. The analysis suggests the FDA rubber-stamped the drug on the basis of a single poorly designed clinical trial that overlooked safety concerns.

The investigation, conducted by the nonpartisan Project on Government Oversight (POGO), concludes that in the agency’s dealings with Pradaxa’s maker Boehringer Ingelheim it deferred its own concerns about proper trial design and safety labeling to the company’s wishes. Those findings and others were presented in a report released Thursday that highlights flaws at virtually every stage of the FDA’s approval process for Pradaxa. The nonprofit watchdog organization says the agency practiced poor oversight and supported inadequate marketing claims for the medicine.

POGO’s damning report comes at a time when Congress is considering the 21st Century Cures Act, a measure that would hasten the FDA’s drug approval process and increase the agency’s workload. POGO says the case of Pradaxa is a “cautionary tale” for the proposed legislation. The Senate will vote on the bill sometime this fall but faces pushback from critics that say it will lead to a flood of new treatments that are not properly vetted. The act introduces flexible forms of clinical trial design that some have argued are too subjective. The FDA’s Science Board has also pointed out that it gives the agency far more work without a sufficient increase in budget.

“We're concerned that it will open doors for things to be made worse rather than better,” Danielle Brian, executive director of POGO, says. “It really looks to us like it's been written by the drug industry. We hope this report will help educate Congress that this is not the way to go.”

Unstoppable Bleeding

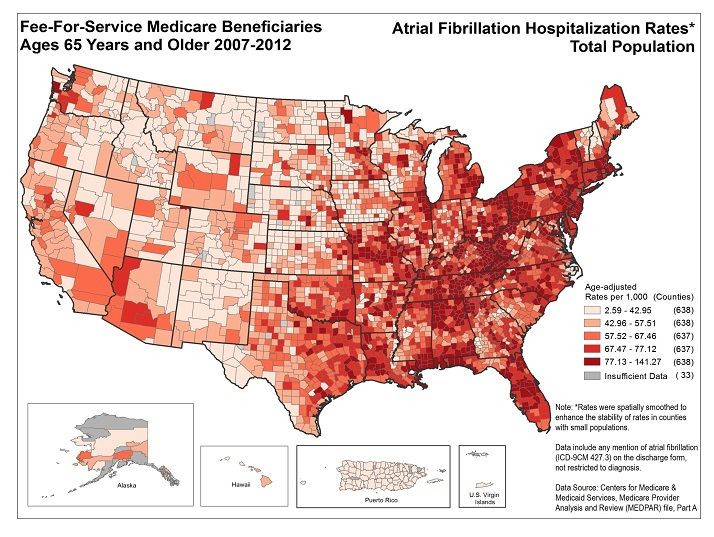

Long before the debate over the Cures Act, the FDA approved Pradaxa in 2010 to prevent blood clots and strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation, which affects between 2.7 million and 6.1 million Americans. Pradaxa had one main advantage over an existing generic competitor called warfarin. Patients on warfarin were supposed to undergo blood tests to ensure that their blood did not become too thick or too thin while on the medicine. Pradaxa required no such tests.

However, there was also a deadly drawback. There is no antidote for Pradaxa that physicians could use to immediately re-thicken a patient’s blood in the case of an emergency. The thinning effects of warfarin can quickly be reversed with a shot of vitamin K but if a patient begins bleeding profusely while on Pradaxa, physicians have no way to stop it.

The POGO report opens with the story of an 81-year-old retired social worker named Sidney Denham who began bleeding profusely from his urinary tract while taking the medicine several weeks after undergoing prostate surgery. When he couldn‘t be replenished with his own blood quickly enough, the doctor who later filled out his death report listed an “uncontrollable hemorrhage from Pradaxa” as a contributing cause.

Dr. Bryan Cotton has witnessed this in his own patients at the University of Texas Medical Center in Houston, Texas. Since Pradaxa’s approval, Cotton estimates that about 25 patients have come to the emergency room with uncontrollable bleeding following an injury while on the drug. He wrote up his observations and published them in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011.

“I'll tell you my first experience with it as a trauma surgeon was seeing these patients come in that were bleeding that we couldn't fix,” he says. “The most frustrating thing is going out and telling the family that the patient died or that they're bleeding uncontrollably. None of these patients know that the drug is irreversible.”

Boehringer Ingelheim is now seeking approval for an antidote, five years after the drug was first approved. Despite that omission, the drug was an immediate success -- sales reached $1.4 billion by 2012 and by 2014, around 935,000 people had received a prescription for it.

However, patients soon began to file complaints about spontaneous or uncontrollable bleeding that they suspected occurred as a result of the drug. POGO says that Pradaxa was cited more than any other drug in adverse event reports submitted to the FDA in both 2011 and 2012, which are sent by patients or physicians to alert the agency to a side effect from a drug that is already on the market. In addition, Boehringer Ingelheim settled 4,000 claims related to Pradaxa for $650 million in May 2014.

The FDA has maintained that the drug does reduce patients’ risk of stroke and that this benefit outweighs any additional risks. Last year, the agency published an update on the drug’s safety from ongoing studies conducted in Medicare patients that showed the medicine reduces risk of stroke and death compared with warfarin but heightens patients’ risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

“As we’ve previously noted, Pradaxa provides an important health benefit when used as directed,” Sandy Walsh, an FDA press officer, says.

Re-Examining Pradaxa

As part of POGO's investigation, eight of the organization's employees sorted through thousands of pages of files obtained through court cases and open records requests over the span of two years to trace the trajectory of the drug’s approval in light of those claims. The group’s work shows that Pradaxa was approved on the merits of a single clinical trial that was not blinded, which means that researchers knew which patients were taking Pradaxa versus warfarin. An FDA review cited in the report found that researchers even removed patients who were on Pradaxa from the clinical trial if they suffered early side effects that may have turned more serious, thus skewing results in favor of the new drug.

Though the FDA originally urged Boehringer Ingelheim to use a blinded trial, the agency accepted the company’s unblinded results. “The FDA has to stick to their guns,” Brian says. “The FDA needs to have more strength in their convictions, that they're not going to lower their standards and accept pressure just because the industry wants them to do it.”

The original trial was riddled with problems. Boehringer Ingelheim did not define what success would mean until after the trial was completed. Typically, companies must settle these terms before a trial begins to ensure that they do not set them in a way that makes a drug look better than it actually is. But the Statistical Analysis Plan for Pradaxa was finalized on May 8, 2009, which is two months after the trial ended.

Furthermore, an FDA review found that the manner in which the trial was conducted did appear to improve the performance of Pradaxa over warfarin. Patients on warfarin were not regularly tested to ensure that their blood remained within the recommended range of thickness. Because of this oversight, those patients on warfarin may have performed worse than real-world patients who took the drug and were properly monitored.

Due to such biases, POGO calls the clinical trial process for Pradaxa “a sausage factory.” Lauren Murphy, a spokeswoman with Boehringer Ingelheim which is based in Ingelheim, Germany, provided a statement that says the company discussed their clinical trial design with POGO in 2013. “We found the article to be biased and misleading for patients and providers. The points raised have been previously addressed publicly and found to be baseless,” the company says.

A Shaky Redaction

Another set of documents suggested the agency bowed to the company’s wish to make advertising claims that Pradaxa was superior to warfarin. In the trial, 3.4 percent of patients on warfarin suffered a stroke compared with 2.2 percent on Pradaxa, but flaws in trial design gave Pradaxa a clear advantage.

At least one FDA leader insisted that a superiority claim was inappropriate due to these flaws and would lead patients on warfarin to believe that they should switch to Pradaxa when it wasn’t clear that they would benefit from doing so. However, his statement was hidden from public view until the POGO report was released.

In 2010, Ellis Unger, the deputy director of the Office of New Drugs at the time, posted a memo to the FDA’s website explaining the agency’s rationale for approving Pradaxa, which is also known by its scientific name dabigatran. The FDA originally redacted a portion of Unger’s statement and said the redaction was intended to protect trade secrets. But the deleted section of Unger’s memo, obtained by POGO, appears to have little to do with trade secrets. Instead, it casts into question the FDA’s decision to eventually allow Boehringer Ingelheim to make superiority claims for Pradaxa.

The redacted section of Unger’s memo reads, “It is important, therefore, not to provide dabigatran with a superiority claim to warfarin, because it would imply that even those well-treated with warfarin should be switched to dabigatran. Clearly, that is not the case.”

Internal emails obtained from Boehringer Ingelheim also show that at least two company scientists who called for establishing a “therapeutic range” within which Pradaxa would be most effective were silenced by concerns that doing so would compromise its ability to compete with warfarin. The creation of such a range would require patients to be regularly tested, and thus erase the drug’s primary competitive advantage.

Boehringer Ingelheim disputes these claims and the implication that warfarin may be just as good or better for some patients than Pradaxa. “Patient care and the evaluation of medicines are best left in the hands of medical experts. The article is irresponsible as it places in danger patients who may erroneously change their medication or behavior without speaking to a healthcare professional,” the company says. “We take offense to anyone or any organization who would question our integrity. ”

To Cotton, the FDA’s willingness to approve a blood thinner without an antidote represents a gross miscalculation. He is similarly offended by the fact that so few primary care physicians seem to inform their patients about the risks of Pradaxa.

“I am frustrated but I am still a little bit in the dark as to how the hell it happened,” he says. “I just know the real-world consequences of having a blood thinner without an antidote. It just freaks me out.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.