Japanese Space Debris Collector, JAXA’s Kounotori6, Fails To Deploy Junk-Fishing Net

Six decades of space exploration has produced a wealth of knowledge for humankind, allowing us to penetrate the mysteries of the universe and our place in it. And while we may still have a very long way to go in the field, spacecraft are leaving a distinct human print in, well, space.

If it were just flags or rovers on the moon, or another planet, it would have not been a great cause of concern. But the space debris locked in orbit around Earth is. Formed by spent rocket parts, disused satellites and spacecraft parts, over 500,000 pieces of debris — each larger than a marble — are currently tracked as they orbit Earth. And moving at speeds of as much as 17,500 miles an hour, even a small piece is potentially dangerous for any spacecraft, such as the International Space Station (ISS), it hits.

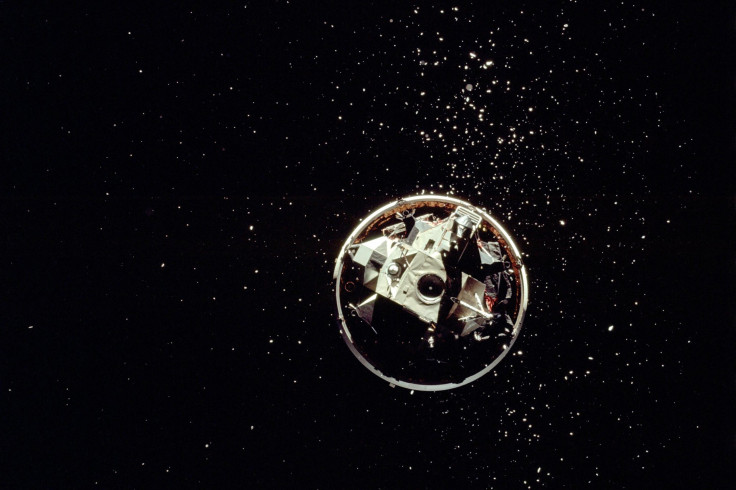

To tackle this problem and to alleviate the risk it poses, Japan’s space agency JAXA tried an experiment, which was launched aboard a cargo spacecraft that was headed for the ISS. Kounotori6 took off from Earth on Dec. 10, and after completing its delivery at the space station, it was supposed to use a novel method to rein in some of the debris in orbit.

The spacecraft (kounotori means stork in Japanese) left ISS Jan. 28 and began its way back to Earth. Its design included a 700-meter (about 3,000 feet) long electrodynamic tether made of aluminum and steel. The tether was made in collaboration with a Japanese fishing net manufacturer Nitto Seimo, and once deployed, it was supposed to have generated electricity using Earth’s magnetic field to slow down and push debris into lower orbit, where it would burn up in the atmosphere during reentry.

However, the tether failed to deploy in the eight days it took for Kounotori6 to reenter the atmosphere early Monday morning, where it burnt up somewhere over the Pacific Ocean, ending its mission.

Koichi Inoue, who headed the tether experiment team, told reporters: “We believe the tether did not get released. … It is certainly disappointing that we ended the mission without completing one of the main objectives.”

Hopefully, the advent of resuable rockets, such as those used by SpaceX, will reduce the increase in the amount of space junk. The U.S. Air Force is working on a new radar system, expected to come online in 2019, to track space debris, and a team of Swiss researchers is trying to make a spacecraft that will swallow tiny pieces of junk, like a space-faring Pac-Man.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.