Jupiter Space Mission: Juno Probe Data Captures Ghostly Sounds From Planet's Auroras

As NASA's Juno spacecraft made its first full orbit around Jupiter, flying 2,600 miles above the gas-giant planet’s swirling clouds, an instrument on board was carefully listening to noises emitted from the planet’s auroras—bursts of light created when electrically charged particles in the atmosphere of a planet collide. The University of Iowa recording device, called Waves, captured radio emissions that were later converted into sound files by engineers from the university. The result: ghostly-sounding transmissions coming from above the planet.

The auroras on Jupiter, the largest planet in our solar system, are similar to those on Earth—the northern and southern lights—except they are more extreme. Jupiter’s auroras are larger in size, are “ hundreds of times more energetic ,” and never come to an end. Scientists have known since the 1950s of the emissions from Jupiter’s auroras. But, according to NASA, they never had up-close samples or the opportunity to analyze them from close proximity. That is, until data came in from Perijove 1—the Aug. 27 mission where the spacecraft, which entered orbit on July 5, closely flew by Jupiter.

"Jupiter is talking to us in a way only gas-giant worlds can," said Bill Kurth, research scientist at the UI and co-investigator for Waves, in a statement. "Waves detected the signature emissions of the energetic particles that generate the massive auroras that encircle Jupiter's north pole. These emissions are the strongest in the solar system. Now we are going to try to figure out where the electrons that are generating them come from."

The next step is for the Waves tool, which presents data as audio stream and color animation, is to gather samples from plasma waves in the magnetic field lines with each future orbit around the planet. The idea is for the scientists to learn more about how electrons and ions move along the magnetic field lines and collide with the atmosphere—this collision is what creates the light show.

What exactly are plasma waves? Kurth drew comparisons to a stringed instrument like a violin.

"If you pluck a string on a violin, the string vibrates," said Kurth. "The vibrating string is like the plasma itself; in the plasma it is the charged particles that are moving."

In their natural setting, the radio waves emitted from the auroras cannot be heard. In order to hear sounds, Kurth said the waves need to be “downshifted” to a specific audio range and then compressed to turn hours of noise into a condensed version.

"We like to listen to them,” said Kurth. “We figure if we like to listen to them, others will too.”

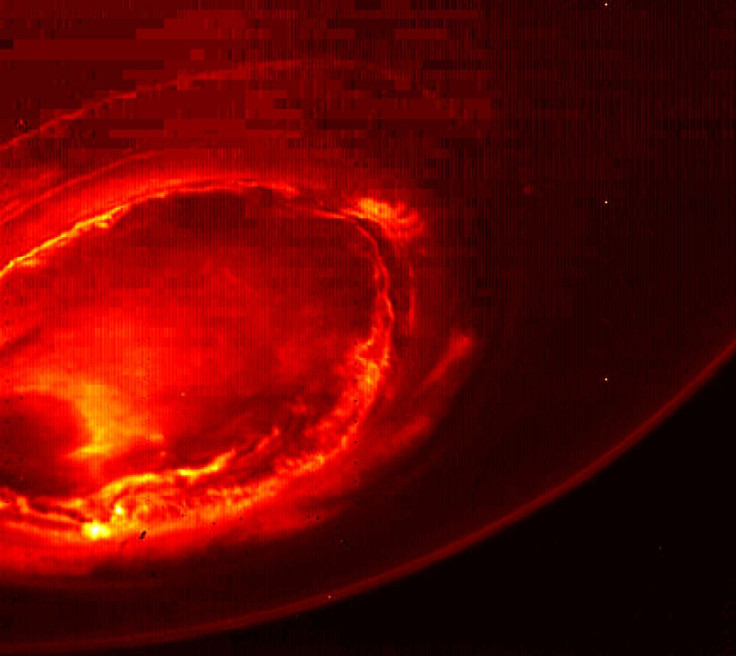

Earlier this year, Juno sent back the first-ever images of Jupiter's north pole from the same flyby mission. Scientists were alarmed by the first views, saying it looked unlike anything they had seen before.

“First glimpse of Jupiter’s north pole, and it looks like nothing we have seen or imagined before,” said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, at the time. “It’s bluer in color up there than other parts of the planet, and there are a lot of storms. There is no sign of the latitudinal bands or zone and belts that we are used to -- this image is hardly recognizable as Jupiter. We’re seeing signs that the clouds have shadows, possibly indicating that the clouds are at a higher altitude than other features.”

The Juno spacecraft, part of NASA's New Frontiers Program, launched on Aug. 5, 2011 from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Perijove 1 was the first of 36 flybys planned, which will take continue until Feb. 2018. But the one earlier this summer, the first, is the closest the spacecraft will get to the planet. The next set of data will be gathered on Nov. 2.

"It just kind of whets our appetite for what to expect," Kurth said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.