Karate Hoping To Land Killer Tokyo Blow Before Olympic Knockout

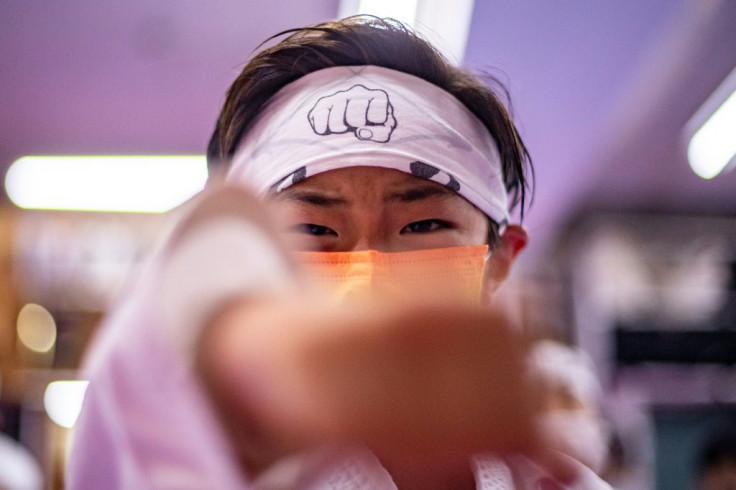

From Cobra Kai to Chuck Norris, karate is known around the world -- but practitioners of the Japanese martial art are hoping the Tokyo Olympics can bring an even wider audience.

After decades of campaigning, karate finally chops its way onto the Olympic stage in Japan as one of four sports making a Games debut.

But the International Olympic Committee's decision to drop it from the 2024 Paris Games means it only has one shot to make an impact.

In Japan -- birthplace of the high-kicking, hard-punching martial art -- practitioners young and old want the sport to leave a lasting impression on global viewers.

"I watch the athletes who are going to be at the Olympics and I think they're so cool," nine-year-old Yusei Iwai told AFP at a Tokyo karate dojo, after going through a series of warm-up exercises with around 30 classmates.

"Karate becoming an Olympic sport means lots of different people will learn about its culture and history and find out what's so good about it."

Karate arrived in mainland Japan from the southern Okinawa islands in the early 20th century, and quickly became popular as a form of self-defence.

But its true essence goes far beyond just punching and kicking, becoming a part of everyday life for those who practise it.

"You don't have to wear karate gear to practise," said 72-year-old Yukimitsu Ono, who has been doing karate for around 55 years.

"When I'm on the phone, I stand on one leg. When I'm chopping something in the kitchen, I stand with my legs spread apart and braced. It's become natural for me."

Olympic karate is split into two competitions -- kumite and kata.

Kumite involves two fighters trying to land blows on each other in bouts of up to three minutes, while kata sees athletes perform choreographed moves for the judges to score.

Karate officials have been pushing for the sport to be included in the Olympics since the 1970s, and the athletes taking part this summer are excited to finally be there.

"It feels significant that the first time karate is appearing at the Olympics is in Tokyo," said Mayumi Someya, who will represent Japan in the women's 61kg kumite competition.

"I think it's important that we convey the appeal of karate when we appear at the Games."

Karate's image took a body-blow earlier this year though, when a Japanese official was forced to resign after being accused of bullying by former world champion Ayumi Uekusa.

Uekusa, who will compete at the Tokyo Games, said Masao Kagawa hit her in the face with a bamboo sword in training, leaving her with a bruised eye.

But karate afficionados insist the sport has become much safer over the years, and are hoping the Games can help it shed its stern image.

"Before karate got into the Olympics, parents used to enrol their kids because they wanted to toughen them up -- kids who were quiet or who would cry a lot," said Tomokatsu Okano, who owns a chain of karate dojos in Japan and the United States.

"Nowadays, it's become bigger, and kids want to do it as a sport. A lot of the kids join because they themselves want to do it."

Okano still preaches the non-sporting benefits of karate, saying it "fills the gaps that schools leave".

"You learn etiquette," he said. "Some people don't like to make eye contact. Schools don't teach kids how to speak properly.

"We want to teach them things that they can use in their everyday lives."

The World Karate Federation has simplified competition rules leading up to the Tokyo Games, but Okano worries they might still be too complicated for casual viewers.

"Anyone watching needs to be able to tell for themselves who has won and who has lost," he said.

Olympic fever is certainly rising among his students, who warm up by hopping around cones and tip-toeing over wooden poles at his cramped dojo.

"I'd like to compete in the Olympics and become famous," said 11-year-old Yua Nose.

"But I'd also like to show everyone how hard I've worked and how strong I've become."

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.