Mental Health In US Prisons: Local And State Governments Make First Nationwide Pledge To Improve Options For Inmates

Local governments and a leading psychiatric association are launching a program to keep convicted criminals with mental illness from landing behind bars and beef up the services offered to current inmates in state prisons and county jails.

Two million Americans with serious mental illness are locked up in county jails each year and many others occupy cells in state and federal prisons. Experts agree that prisons and jails are no place to treat mental illness, but these facilities have become the de facto mental hospitals throughout most of the U.S. Oftentimes, advocates say, mentally ill inmates do not pose a threat to others and could receive better treatment from within the community.

While legislation introduced to Congress in April would address mental illness within the prison system at the federal level, this new alliance called the Stepping Up Initiative is the first nationwide collaboration between local and state governments to focus on the issue, says Renee Binder, president of the American Psychiatric Association which is a partner in the new program.

“The basic issue is that people with severe mental illness do not belong in the criminal justice system and they do very poorly once they are in jail,” Binder says. “The vast majority of people can be treated in the community facilities under community supervision.”

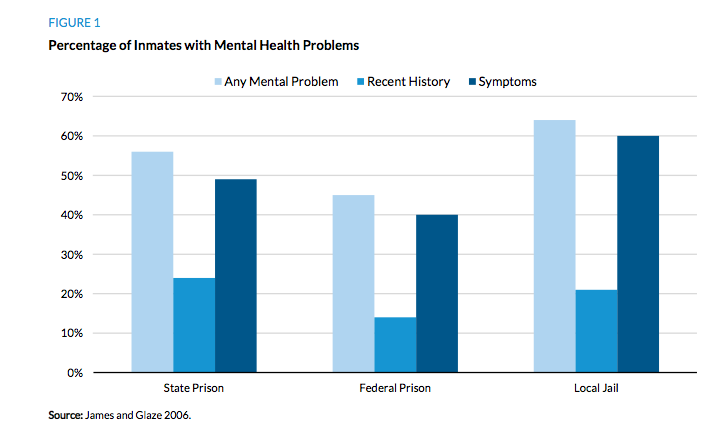

The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated in 2006 that 56 percent of prisoners in state prisons and 64 percent of inmates in local jails suffer from some form of mental illness. Those who are released are far more likely to return to jail or prison in the future than inmates without mental health problems.

The leaders of Stepping Up say that the chronic incarceration of the mentally ill “does nothing to improve public safety, stresses already strained budgets and hurts people with mental illnesses and their loved ones.”

Through the new program, county and state governments that manage prisons and jails will share strategies that have proven to cut the number of mentally ill inmates within a prison system, or reduce recidivism among those undergoing treatment. Stepping Up requires government leaders who join to first survey the instance of mental illness in area jails and pledge to develop an evidence-based plan with metrics for reducing that rate. The program launched in early May and so far, about 30 counties from Sandoval County, New Mexico to Lake County, Ohio have signed up. There are roughly 3,000 counties in the U.S.

Many government employees or nonprofits that come to the aid of mentally ill people who face charges simply point them in the direction of existing social services which may or may not be well-adapted to serve the mentally ill. Program leaders point to an NYC-based program called the Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services (CASES) as exemplary of the community-based approach that they hope participants will implement.

When CASES was founded in 1989, employees built their own service department with a full staff of case workers, substance abuse counselors and psychologists. CASES staff therefore control more aspects of a client’s treatment and provide extra support while they navigate these services. The CASES staff also advocates on clients' behalf for probation and community service or a stint at rehabilitation rather than jail time. Employees fully support clients throughout sentencing, probation and beyond and report back to the court on their progress.

“If everything is ok, they continue on in the community but if they’re not doing what the judge and court expect, they’re at risk of losing their liberties,” Ann-Marie Louison who directs adult behavioral programs for CASES, says.

In addition to highlighting succesful programs such as CASES, Stepping Up will also advise county and state governments on how to build a budget that includes mental health services or alternatives to incarceration. This approach can save money -- one sheriff in Michigan has said that it costs $31,000 a year to house an inmate with mental illness but only $10,000 a year to treat that same person through a community-based group.

The three partners behind the initiative are the National Association of Counties, the Council of State Governments and the American Psychiatric Foundation which is the philanthropic arm of the American Psychiatric Association.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.