Mystery Of Spanish Flu Pandemic Solved? ‘Missing’ Link Shows Why 1918 Virus Targeted Young Adults

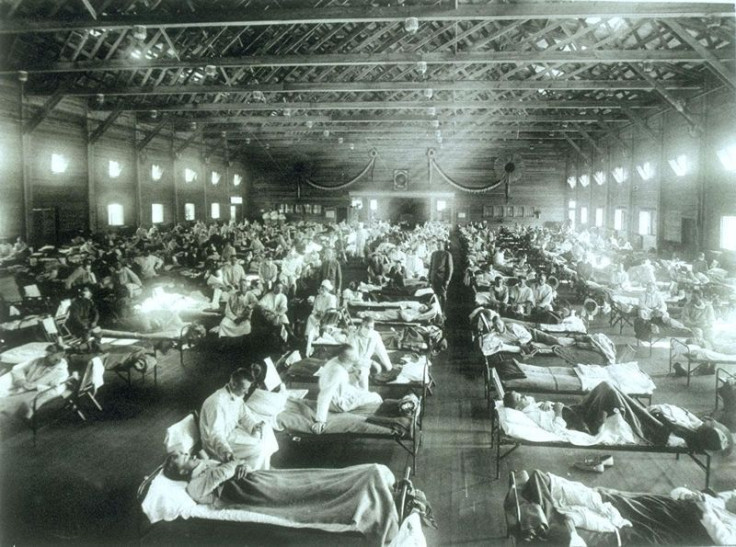

The Spanish flu pandemic, also called the 1918 flu pandemic, is one of history’s greatest biomedical conundrums, primarily because of whom the virus targeted. But new research is helping lay some of the mystery surrounding the world’s deadliest flu pandemic to rest.

Researchers from the University of Arizona announced Monday that they may have an answer to why the early 20th-century pandemic that killed 50 million people -- 3 percent of the world’s population -- disproportionately infected young, healthy adults, a question that has had scientists scratching their heads for decades.

The reason, scientists say, has to do with the nature of the influenza virus. The 1918 flu virus was a hybrid virus that consisted of genetic material from an already circulating human H1 virus and a bird flu virus. Older people had a natural defense against the strain; they had been exposed to similar strains before.

People born after 1889 had not developed partial immunity to these strains because they were not exposed as children to the kind of flu virus that struck in 1918, leaving them particularly vulnerable to its effects.

In short, the dominant strains of influenza in the early 20th century were different than they were a generation earlier.

"It sounds like a modest little detail, but it may be the missing piece of the puzzle," Michael Woroby, a professor in the University of Arizona Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and lead author of the study, said in a statement. "Once you have that clue, many other lines of evidence that have been around since 1918 fall into place."

In 1917, the life expectancy for someone living in the U.S. was roughly 51 years. A year later, U.S. life expectancy plummeted to just 39, Time noted.

That’s because the 1918 flu pandemic killed 650,000 people in the U.S. alone, and many of the victims were men and women in their 20s and 30s.

"You have the most deadly flu pandemic in history essentially leaving the elderly, its most frequent victims, completely alone," Woroby told National Geographic.

The study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, looked at how seasonal flu strains evolved differently and at different speeds in people, birds and pigs. Creating historical models that accounted for these nuances gave researchers a better idea of exactly what strain of influenza virus fueled the Spanish flu pandemic.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.