'Northern Lights' In Space: This Comet Has Its Own Ultraviolet Aurora

KEY POINTS

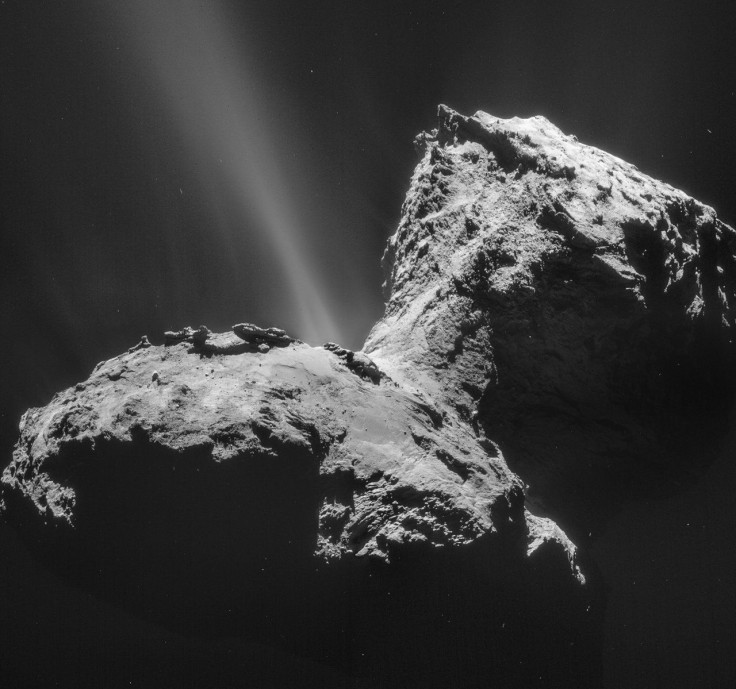

- Researchers using Rosetta data found that comet 67P/C-G has its own aurora

- It is the first detection of an ultraviolet aurora on a comet

- Rosetta mission had already ended but it continues to provide valuable data

Observations from the Rosetta spacecraft revealed that comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (C-G) actually has its own aurora, making it the first comet to be observed with far ultraviolet auroral emissions.

Auroras on Earth happen when charged particles from the sun interact with the planet’s magnetic field, forming the colorful ribbons of light in the northern (aurora borealis) or southern (aurora australis) regions. Although they are some of the most spectacular phenomena on Earth, they're not exactly unique to our planet because other celestial bodies such as moons and other planets can display auroras as well.

But in a new study, a team of researchers is reporting the discovery of an aurora that has not been observed before: a far ultraviolet aurora at a comet.

In the study, published in the journal Nature Astronomy, the team described their observations of comet 67P/C-G using data from NASA and Southwestern Research Institute (SwRI) instruments aboard the European Space Agency's (ESA) Rosetta spacecraft. They found that the UV emissions that were previously thought of as mere "dayglow" were actually the comet's own aurora in far-ultraviolet light.

"We were amazed to discover that the UV emissions are aurora, driven not by photons, but by electrons in the solar wind that break apart water and other molecules in the coma and have been accelerated in the comet's nearby environment. The resulting excited atoms make this distinctive light," study co-author Dr. Joel Parker who leads one of the instruments used in the study said in a SwRI press release.

Comets have auroras too! ☄ Our instruments aboard the @ESA_Rosetta spacecraft have helped reveal that a comet has its own far-ultraviolet aurora. About this first-ever finding on a celestial object other than a planet or moon: https://t.co/BAwlgGD16A pic.twitter.com/34llumwE7t

— NASA (@NASA) September 22, 2020

Simply put, when the gas around the comet, called a "coma," gets excited by solar particles, the high-energy process results in a distinctive ultraviolet glow, thereby creating an aurora.

"The resulting glow is one of a kind," study lead Marina Galand of Imperial College of London further explained in a news release from the University of Bern. "It's caused by a mix of processes, some seen at Jupiter's moons Ganymede and Europa and others at Earth and Mars."

Although the comet's aurora is not visible to the naked eye because, as a NASA news release explains, far-ultraviolet has the shortest wavelengths of radiation in the ultraviolet spectrum, the discovery is actually an interesting first.

"It is the first time such electromagnetic emissions in the far-ultraviolet have been documented on a celestial object other than a planet or moon," the NASA news release said.

Although the ESA's Rosetta spacecraft had ended its mission in 2016 when it landed on comet 67P/C-G, the data that it captured continues to provide valuable information. For instance, earlier this year, a team of scientists were also able to explain why comet 67P/C-G appears to have changed in color from red to blue, then back to red again from January 2015 to 2016 using previously acquired Rosetta data.

"Rosetta is the gift that keeps on giving," study co-author Paul Feldman of Johns Hopkins University said in the NASA news release. "The treasure trove of data it returned over its two-year visit to the comet have allowed us to rewrite the book on these most exotic inhabitants of our solar system – and by all accounts there is much more to come."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.