Outbreaks Spread Four Times Faster From Black Death To Great Plague

KEY POINTS

- Plague outbreaks spread much faster in the 17th century than in the 14th century

- A team of researchers tried to find possible reasons behind the increased speed

- Scientists said the mode of transmission might have changed over time

Just how fast did the plagues spread? A team of researchers found that plague outbreaks in London spread much faster in the 17th century than they did in the 14th century.

Both the Black Death and the Great Plague are infamous moments in history that took many lives. In a new study, a team of researchers analyzed historical records and found a pattern of plague transmission, which was much faster in the latter period compared to the former.

The researchers found that the plague transmission in the 14th century doubled every 46 days. By comparison, the transmission doubled every 11 days in the 17th century, a news release from the McMaster University explains.

This means that within a period of 300 years, the plague transmission in London became four times faster. Their findings were also consistent with the available death counts.

"It is an astounding difference in how fast plague epidemics grew," study lead David Earn, of McMaster University, said in the news release.

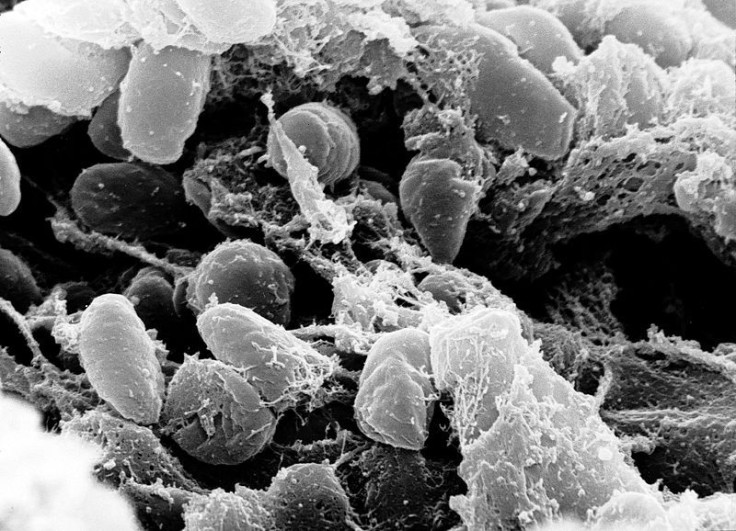

What's interesting is that the strain that caused these epidemics, the Yersinia pestis, did not change much during the time, the researchers said. And even today, how it was actually transmitted remains a mystery.

So how did the spread of the disease accelerate at such a pace?

It's possible that the mode of transmission may have changed, with the earlier, slower epidemic having spread through infected fleas (bubonic plague) bites while the latter epidemic being spread from human to human (pneumonic plague), which is believed to be a much faster way of spreading. But this, too, is difficult to prove as both the epidemics are more consistent with the bubonic plague rather than pneumonic plague, the researchers note.

The researchers also considered the population density and living conditions during those periods. Between the earlier and later epidemics, population size and density in London "increased enormously" and this would have affected the density of the rat and flea populations.

"In addition, higher rat densities make it more likely that fleas departing dying rats end up on susceptible rat hosts," the researchers wrote.

The climate also changed between the 14th and 17th centuries, with the 17th century being the coldest period of the Little Ice Age. This may have contributed to the changes in plague transmission.

These are, however, mere possibilities and what really caused the substantial acceleration in the spread of the disease remains a mystery.

"Why the later plague epidemics were faster than the earlier ones is not clear," the researchers wrote.

The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.