Planet Nine Might Not Be Responsible For Bizarre Orbits Of Distant Objects

Scientists have witnessed a bunch of "detached" celestial bodies with weird orbits in the outer edges of our solar system. These objects look separated from the rest of the neighborhood, something that many think could be the outcome of the gravitational pull of another massive planet, famously called Planet Nine, hiding somewhere beyond Neptune.

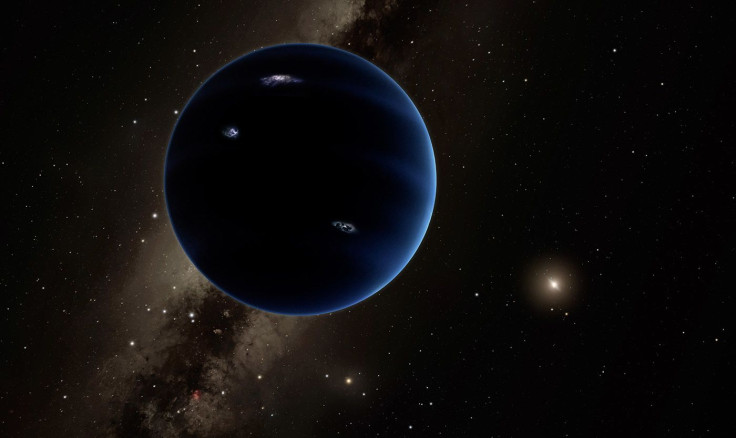

Though no evidence suggests a ghostly planet exists in our stellar system, theories of the hypothetical planet, which is said to be 10 times the size of Earth, have been doing rounds for almost two years. The theories further got fanned with the orbital explanation. However, a new study exploring the interaction between icy trans-Neptunian objects sitting in the outer parts of our solar system hints that the collective gravity from these objects, and not Planet Nine, might be responsible for the strange orbits of the detached objects.

“There are so many of these bodies out there. What does their collective gravity do?” Ann-Marie Madigan, from University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder), said in a statement. “We can solve a lot of these problems by just taking into account that question.”

Madigan and team weren’t exactly looking to explain the strange orbits of these bodies, but when Jacob Fleisig, the lead author of the study, ran a series of simulations to study the dynamics of these bodies, they were totally surprised.

“He came into my office one day and says, ‘I’m seeing some really cool stuff here,’” Madigan said.

The work revealed that icy objects beyond Neptune move around the sun just like the hands of a clock, with smaller bodies moving quickly than bigger ones such as Sedna — a minor planet that takes 11,000 years to complete a single orbit around the sun.

“You see a pileup of the orbits of smaller objects to one side of the sun,” Fleisig said in the statement, explaining the point when the two hands meet. “These orbits crash into the bigger body, and what happens is those interactions will change its orbit from an oval shape to a more circular shape.”

Put simply, the collective gravity from the smaller objects should have kicked up the orbit of the bigger ones, taking them into the odd category of detached objects. This explains the oddball behavior of Sedna, which is a little smaller than Pluto but follows a massive, circular orbital path to circumnavigate the sun, just like other detached objects. Sedna circles the sun at a distance of nearly 8 billion miles and doesn’t even come near solar system’s giant planets.

More importantly, the work could also shed some light on the catastrophic demise of dinosaurs on Earth. According to the researchers, the interaction between space debris and bigger objects in the outer solar system could have triggered repeated orbital changes, which in turn, could have shot comets toward the inner part of the neighborhood, including Earth. “While we’re not able to say that this pattern killed the dinosaurs,” Fleisig added, “it’s tantalizing.”

The work explaining the collective gravity theory was presented at a press briefing at the 232nd meeting of the American Astronomical Society, which runs from June 3-7 in Denver.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.