Saturn’s Moons May Be Much Younger Than Previously Thought

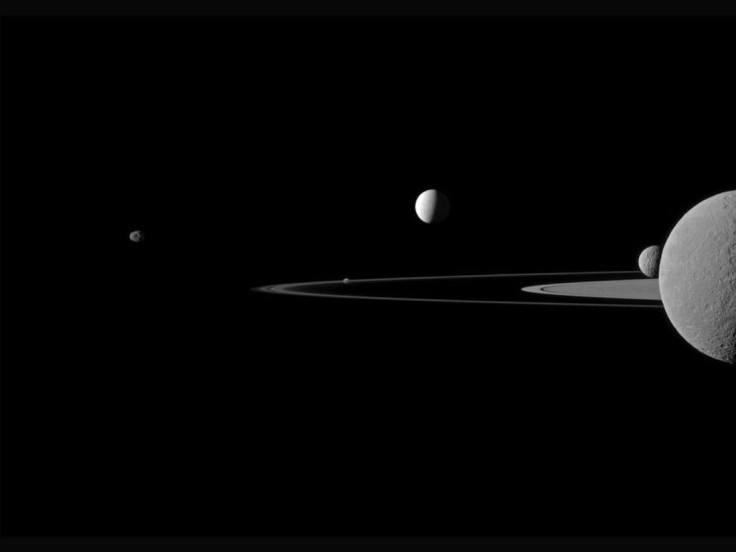

Saturn — the second-largest planet in the solar system — has at least 62 confirmed moons, of which 53 have been officially named. Analysis of fresh data gathered by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft now suggests that these moons may be much younger than previously believed.

In a study published in the latest edition of the journal Icarus, researchers from Cornell University and a Europe-based scientific team Encelade used measurements of what’s known as the Love number to determine that the gas giant’s moons were moving away from the planet faster than previous estimates indicated.

Most moons slowly move away from the planets they are orbiting because of the gravitational pull exerted by tidal bulges. Earth’s moon, for instance, is currently moving away at a rate of roughly 1.5 inches per year.

While Saturn does not have any oceans on its surface, it is suspected to possess a rocky core beneath its thick atmosphere of hydrogen and helium. And, much like Earth’s oceans respond to Moon’s tiny but persistent pull by bulging outward, this core also responds to the pull exerted by Saturn’s many moons.

For this particular study, the researchers used century-old photographic images of Saturn and recent observations made by the Cassini spacecraft to calculate Saturn’s Love number — a quantity that, among other things, describes the rigidity of a planet’s tidal bulge. They also found, upon examining the motion of four tiny Saturnian moons — Telesto, Calypso, Helene and Polydeuces — that the orbits of these objects were being disturbed by the gas giant’s tidal bulges.

“By monitoring these disturbances, we managed to obtain the first measurement of Saturn’s Love number and distinguish it from the planet’s dissipation factor,” study co-author Radwan Tajeddine, an astronomy research associate at Cornell, said in a statement. “The moons are migrating away much faster than expected.”

The researchers then used this rate of the moons’ migration to estimate that if they had actually formed 4.5 billion years ago, as previously believed, they would by now have been much farther away.

This finding bolsters a theory that posits that far from being objects captured by Saturn’s gravity at the beginning of the solar system, these moons formed when material from the planet’s rings clumped together — a process that may still be going on.

“All of these Cassini mission measurements are changing our view of the Saturnian system, as it turns our old theories upside down,” Tajeddine said. “It takes one good spacecraft to tell us how wrong we were in the past.”

The Cassini space probe, which has been orbiting Saturn since 2004, is currently in the midst of ring-grazing orbits — the first phase of what NASA calls the mission “endgame.” Once these ring-grazing experiments are done, Cassini will begin its “grand finale,” during which it will pass just over 1,000 miles above the thick clouds that enshroud Saturn. This would then be followed by a fatal plunge through the planet’s atmosphere on Sept. 15

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.