Stephen Hawking Memoir ‘My Brief History’: Acclaimed Physicist With ALS Opens Up, Sort Of

Anyone who slacked off in college may be comforted to read Stephen Hawking’s admission that, by his calculations, he did about an hour of work a day in his three undergraduate years at the University of Oxford.

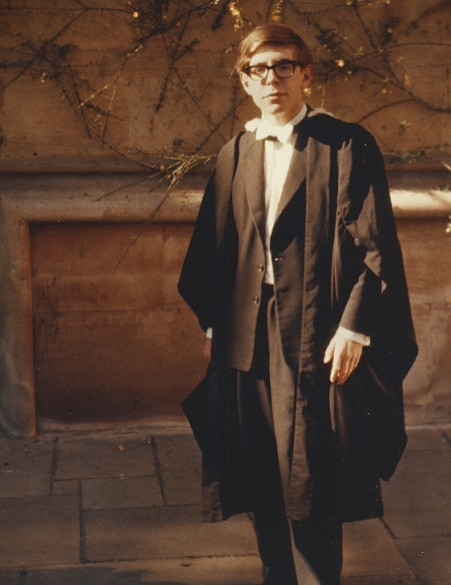

These and other biographical tidbits are sprinkled throughout Hawking’s new memoir, “My Brief History,” a short and occasionally illuminating account of the most recognizable scientist since Albert Einstein. Hawking -- currently the director of research at the Center for Theoretical Cosmology at the University of Cambridge -- has peeked at the origin of the universe and into black holes, while defying medical expectations by living with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, for about a half-century.

“My Brief History” starts at the very beginning, with brief sketches of Hawking’s parents and childhood, and moves forward in a mostly linear fashion through college, graduate school, research and the publication of “A Brief History of Time.” Plodding passages -- “[H]e told me he had originally proposed another candidate for the medal but in the end had decided I was better and had told the academy to award it to me” -- crop up regularly. If you want literary memoir, look to Joan Didion, not Hawking.

Those who thumb past the boilerplate childhood memories will be rewarded with some interesting scientific ruminating later on, including detailed sections on black holes and the possibility of time travel. And, thankfully, Hawking’s dry humor breaks through every now and again.

“I was born on January 8, 1942, exactly three hundred years after the death of Galileo,” Hawking writes. “I estimate, however, that about two hundred thousand other babies were also born that day. I don’t know whether any of them was later interested in astronomy.”

A confessional memoir this is also not. Hawking relates details of his personal life -- most of them already public knowledge -- but doesn’t dwell on them. As a reluctant scientific celebrity, he’s always evinced a keen dislike for the media’s interest in his personal life. But this reluctance carries over into “My Brief History,” infusing the personal parts of the book with flatness.

For instance, Hawking gives his account of how his first wife, born Jane Wilde, installed a man named Jonathan Hellyer Jones in their apartment after she gave birth to Hawking’s third child in 1979. Jones was apparently meant to be a kind of man-in-waiting for when Hawking died. Hawking says he wanted to object, but that he, like everyone else, assumed his disease was about to consume him, and he felt someone had to be ready to look after his children. But by 1990, with Hawking still awkwardly alive, he says he became “unhappy” with the closeness of his wife and Jones. He moved into another house with one of his nurses and eventual second wife, born Elaine Mason, who he divorced in 2007.

This sort of domestic drama could be fodder for a romantic novel all on its own. Hawking covers it in a few paragraphs broken up by a lengthier -- and much more interesting -- description of the various technological measures he has used to communicate after a tracheotomy in 1985 robbed him of the ability to speak.

Meanwhile, Jane Hawking has written not one but two books on her first marriage: “Music to Move the Stars” and “Traveling To Infinity: My Life With Stephen Hawking.” In interviews with the media, she’s frequently voiced her frustration at being described as her husband’s caretaker throughout their marriage, and having her own academic career suppressed by marriage and motherhood. As reported by the Sydney Morning Herald, she speaks three languages, is religious, and wrote her doctoral thesis on medieval Spanish poetry -- details that are not mentioned in “My Brief History.”

The more introspective parts of “My Brief History” come when Hawking discusses his disability, about which he is remarkably upbeat. When he was diagnosed with ALS (called motor neurone disease in the U.K.) in his 20s, it was unclear how quickly the condition would progress, and some doctors gave him just a few years to live. The 71-year-old Hawking, having overshot those estimations by about half a century, doesn’t dwell much on what may have helped him beat the medical odds. When he first learned of his diagnosis, Hawking says he was shocked. But he recounts how that shock was tempered by the sight of a boy of his acquaintance dying of leukemia in the opposite hospital bed.

“Clearly there were people who were worse off than me -- at least my condition didn’t make me feel sick,” Hawking writes. “Whenever I feel inclined to be sorry for myself, I remember that boy.”

Hawking is also frank about the ways that his disability has proved to be an asset. Early on in graduate school, his deteriorating physical condition steered him away from experimental research, since he couldn’t do the more hands-on work required. As a result, he entered the theoretical realms where he’s made his name. His disability also removed the obligation to sit on boring faculty committees or to teach undergraduates, and allowed him to wholly focus on research. He thinks it’s also one of the secrets to his celebrity: “I fit the stereotype of a disabled genius. I can’t disguise myself with a wig and dark glasses -- the wheelchair gives me away.”

Because so much of Hawking’s work concerns the origins of space and time, readers might be looking for some discussion of philosophy or religion. After all, Hawking caused a bit of a stir when he told a California Institute of Technology audience last April that the so-called Big Bang didn’t need any divine intervention to kick-start it, as noted by Space.com. But don't expect to ready about “big picture” implications of cosmology. Unlike more strident atheist-scientists such as Richard Dawkins, Hawking is much more concerned with physics than to metaphysics. For him, God, like the steady-state universe, is just another obsolete theory past its prime.

“My Brief History,” published by Bantam, will be available Sept. 10.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.