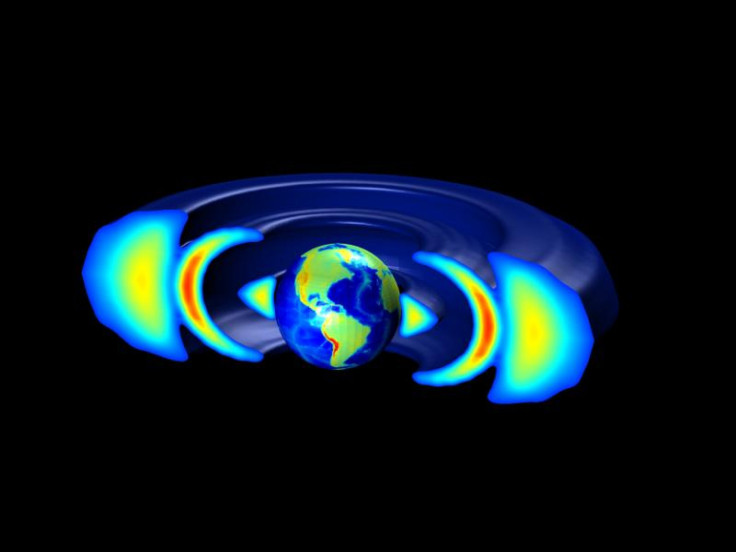

Third Radiation Ring Around Earth Explained, Belt Driven By ‘Very Different Physical Processes’ [PHOTO]

When scientists discovered a third radiation ring that encircled the Earth last year they thought it would resemble the other two. But the ring that persisted for about a month was completely distinct.

New research by scientists at the University of California Los Angles shows that the belt had electrons so energetic they moved nearly at the speed of light.

"In the past, scientists thought that all the electrons in the radiation belts around the Earth obeyed the same physics," Yuri Shprits, a research geophysicist with the UCLA Department of Earth and Space Sciences, said in a statement. "We are finding now that radiation belts consist of different populations that are driven by very different physical processes."

Unlike the two previously discovered Van Allen radiation belts in 1958, the third ring was narrower and comprised of ultra-relativistic electrons – highly energized particles.

"This study shows that completely different populations of particles exist in space that change on different timescales, are driven by different physics and show very different spatial structures," Shprits said.

While the ultra-relativistic electrons exist in the two other radiation rings, these findings show that the Van Allen radiation rings "can no longer be considered as one consistent mass of electrons,” Shprits said.

Shprits and his team found the third radiation belt on Sept. 1, 2012 after plasma waves "whipped out ultra-relativistic electrons in the outer belt almost down to the inner edge of the outer belt." After the storm, a third ring “less compact belt of electrons” formed creating a third “storage ring between the two Van Allen ones. It later decayed and was destroyed by an “powerful interplanetary shockwave,” according to a statement.

“It was so odd looking, I thought there must be something wrong with the instrument,” U-Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics director Dan Baker said in an earlier statement following the third ring’s discovery. “But we saw things identically on each of the spacecraft. We had to come to the conclusion that this was real.”

Scientists remained puzzled why the storm killed the third ring, while the other two reformed. “We have no idea how often this sort of thing happens,” Baker said. “This may occur fairly frequently but we didn’t have the tools to see it.”

While more research needs to be done on the effects of radiation in space, the Van Allen radiation rings may pose a “severe danger to satellites and spacecraft,” Shprits said. The Van Allen rings, found in 1958 by Explorer I, the first U.S. satellite that traveled to space occupy a space ranging from about 1,000 to 50,000 kilometers above the Earth's surface.

"I believe that, with this study, we have uncovered the tip of the iceberg," Shprits said. "We still need to fully understand how these electrons are accelerated, where they originate and how the dynamics of the belts is different for different storms."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.