Tiny Ancient Reptile Escaped Predators By Losing Its Tail, Lizard-Style

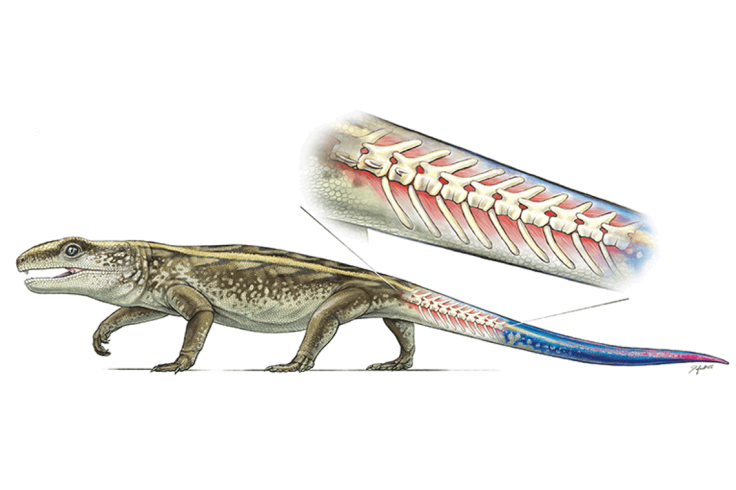

About 289 million years ago, our planet was populated with tiny reptiles possessing some unusual abilities to evade falling prey to carnivorous creatures. Scientists say these prehistoric creatures, called Captorhinus, were capable of ripping themselves apart to avoid predators.

The ancient reptiles lived during the Early Permian period and could “detach their tails to escape the grasp of predators.” A new study suggests this is the oldest known example of such behavior among animals.

Captorhinus are considered the distant relatives of modern reptiles. These tiny creatures weighed less than two kilograms. Captorhinus and their relatives were both omnivores and herbivores and were faced with foraging for food while attempting to avoid being eaten by meat-eating amphibians and ancient relatives of modern mammals.

“One of the ways captorhinids could do this was by having breakable tail vertebrae ,” Aaron LeBlanc, a PhD student at the University of Toronto and lead author of the new study, said in a statement. “Like many present-day lizard species, such as skinks, that can detach their tails to escape or distract a predator, the middle of many tail vertebrae had cracks in them."

“If a predator grabbed hold of one of these reptiles, the vertebra would break at the crack and the tail would drop off, allowing the captorhinid to escape relatively unharmed,” said Robert Reisz , a professor of biology at University of Toronto and co-author of the new study said.

As part of their study, the researchers analyzed a treasure trove of fossils found at cave deposits near Richards Spur, Oklahoma. Using various paleontological and histological techniques, the researchers discovered that the cracks found on the ancient reptile’s body formed naturally, during the development of the creature’s vertebrae.

The researchers also discovered that the cracks were well-formed in young captorhinid, while the cracks observed in the adults were apt to merge. This is likely because the young required this particular feature more than adults, in order to defend and protect themselves.

Over 70 tail vertebrae of both young and adult reptiles, as well as partial tail skeletal remains, were examined by the researchers. When researchers compared these skeletons to those of other relatives of captorhinids, they found that only the captorhinids in the Permian period had this unique tail-detaching escape feature.

The study also indicates that captorhinids were the most common reptiles and by the end of the Permian period, about 250 million years ago, these ancient reptiles had even spread across the ancient supercontinent of Pangaea. Researchers believe their unique escape strategy may likely have played a major role in their successful survival. However, this particular trait disappeared from fossil records when these ancient reptiles eventually died out, re-evolving into lizards, around 70 million years ago.

The findings of the new study have been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.