Trial Of Accused 9/11 Mastermind Resumes, Days Before 20th Anniversary

The trial of five men accused in the September 11 attacks restarted Tuesday just days before the 20th anniversary but quickly ground to a halt on technical issues, underscoring that victims of the Al-Qaeda plot could wait much longer for justice.

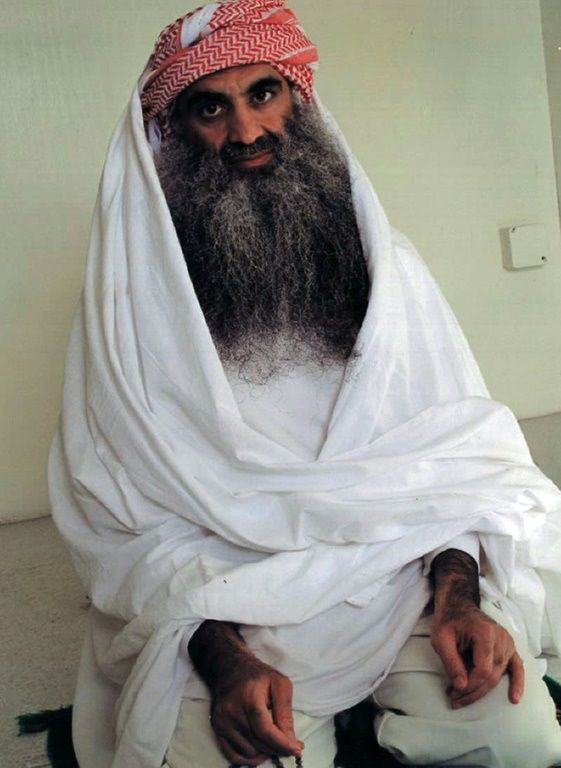

Accused September 11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four others appeared in the military commissions court at the US naval base in Guantanamo, Cuba for the first time in more than 18 months after the death-penalty case emerged from a coronavirus-forced pause.

But the stress of nine years of pretrial battling surfaced almost immediately as the new judge, the eighth assigned to the case, was forced to suspend the hearing after two-and-a-half hours to deal with issues arising from his appointment.

And a military appeals court's new ruling supporting the destruction of a CIA black site where some of the defendants may have been tortured before they came to Guantanamo immediately turned the case back to its central issue: can men who underwent methodical torture be tried fairly with the due process promised by US law?

Tuesday's session began with alleged 9/11 "architect" Mohammed, with a dense, greying red beard, striding into the courtroom with a military escort, followed one by one with his alleged co-conspirators Ammar al-Baluchi, Walid bin Attash, Ramzi bin al-Shibh and Mustafa al-Hawsawi.

The court was packed with military prosecutors, interpreters, military security and five defense teams, one for each defendant.

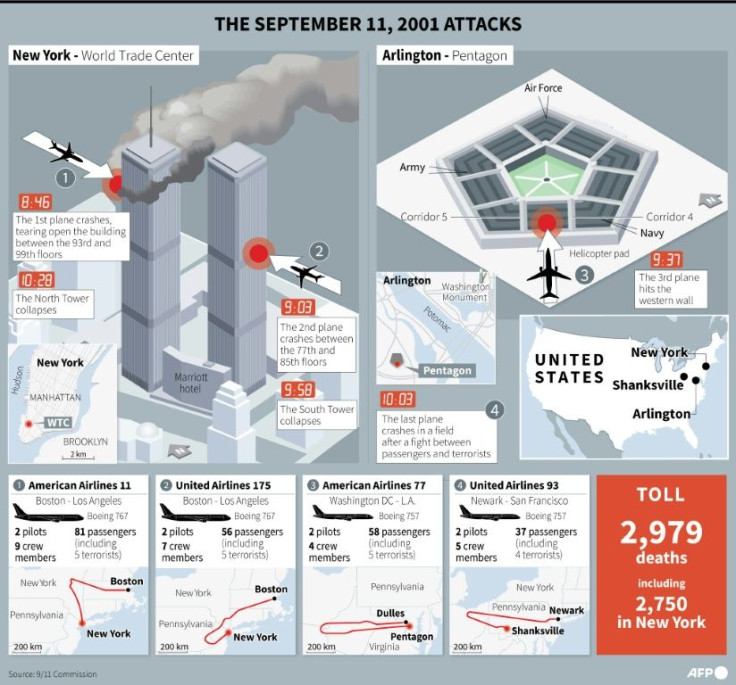

In the public gallery, behind thick glass, were members of the families of the 2,976 people that they are accused of murdering almost exactly 20 years ago.

Mohammed wore a blue turban and matching face mask which he removed to let free a long, flowing beard. He chatted animatedly with bin Attash while leafing through a pile of documents.

Bin Attash, who allegedly helped plan the 9/11 attacks, wore a pink keffiyeh headdress and a military desert camouflage jacket, walking slowly with a prosthetic on one leg he lost in a firefight in Afghanistan in 1996.

Al-Shibh, a member of the "Hamburg Cell" of hijackers, also wore desert camouflage over his white cotton pants, seemingly to reflect his days as an Al-Qaeda jihadist.

Baluchi, also known as Ali Abdul Aziz Ali and the nephew of Mohammed, revealed a short, black beard under his mask and wore a Sindhi cap of his native Balochistan, along with a traditional vest over his white robe. He is accused of handling money transfers in the plot.

The fifth defendant, Hawsawi, who worked together with Baluchi, entered in a Saudi thobe-style white robe. He also carried a pillow which he placed on the hospital chair reserved for him, due to rectal damage his lawyers say was incurred in the abusive interrogations by the CIA.

McCall, who is the eighth to be named to preside, opened by asking each of the defendants if they understood the guidelines for the hearing.

"Yes," each answered, some in English and some in their own languages.

He then launched into a discussion of the need to wear masks when not addressing the court -- though Mohammed and a couple others seemed to ignore it. Some if not all of the defendants have been vaccinated for Covid-19, according to defense attorneys.

Defense attorneys said they were eager to continue where they stopped in February 2019, building a case to discredit the bulk of the prosecution's evidence due to the torture the five endured while in CIA hands between 2002 and 2006.

But immediately an example of their uphill battle to obtain classified evidence surfaced, tied into McCall's appointment.

He was named to preside last year, but it surfaced that he did not yet have the two years experience as a military judge required for the 9/11 case.

In the meantime, before he became qualified last month, another judge was named to temporarily oversee the case.

According to James Connell, an attorney for Baluchi, that judge, acting with Department of Defense support, approved the destruction of one of the CIA black sites used to torture 9/11 detainees, which Connell said was essential evidence.

Connell had appealed, but on Tuesday the military justice system's appeals court ruled in favor of the destruction.

"One of the most important issues in the case is how the torture of these men is going to ultimately affect the trial," said Connell.

"The intentional destruction of evidence takes away from the defense, and really the American people, information about what actually happened," he said.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.