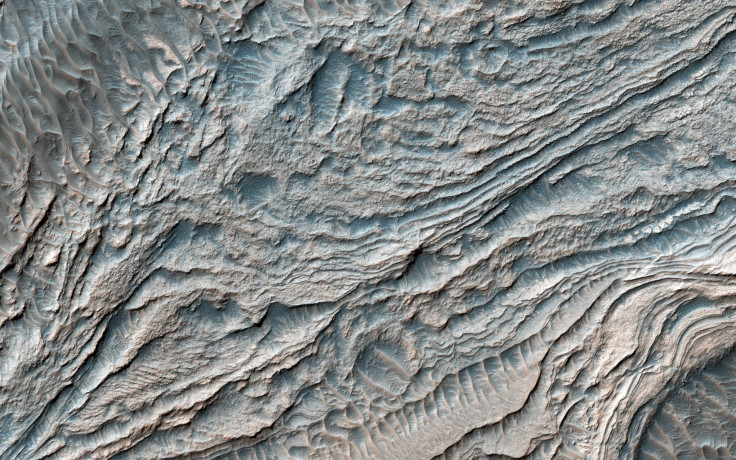

Water On Mars: NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Snaps Image Of Layered Deposits In Melas Basin

In recent years, observations made using NASA’s Curiosity rover and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) have provided ample evidence that water once flowed on Mars’ surface. On Tuesday, the space agency released another image captured by the MRO showing layered deposits of sediments in the Melas Basin.

Scientists believe that the basin, located in the red planet’s southern hemisphere, once had a 1,300-foot-deep lake. According to NASA, the new image, which shows a cluster of steeply inclined light-toned layers bounded above and below by “unconformities,” is indicative of a “break” during which erosion of pre-existing layers was taking place at a higher rate than deposition of new materials.

“The layered deposits in Melas Basin may have been deposited during the growth of a delta complex,” NASA said in a statement accompanying the image. “This depositional sequence likely represents a period where materials were being deposited on the floor of a lake or running river.”

Data previously collected by the MRO and Curiosity has bolstered the theory that roughly 4.3 billion years ago, Mars had enough water to cover its entire surface in a liquid layer about 450 feet deep. Evidence also suggests that long after solar winds stripped the red planet of its atmosphere, turning it into the cold, arid world it is today, lakes of water and snowmelt-fed streams still existed on its surface.

The MRO has been orbiting the red planet since 2006, and has beamed back striking photos of Mars to Earth every month. Last August, NASA published its largest dump of images captured by the MRO’s HiRise camera, releasing a cache of over 1,000 photos that show the Martian surface in all its glory — from dunes and craters to mountains and ice caps.

All the photos in the image dump were taken in May, when Mars experienced its equinox — a period during a planet’s orbit when the sun shines directly on its equator, lighting up both its poles. Coincidentally, as Alfred McEwen, the director of the Planetary Image Research Laboratory, explained to Popular Science at the time, the equinox overlapped with the period when Mars and the sun were on the opposite sides of Earth — a phenomenon that facilitates unobstructed communication between the MRO and ground control.

As a result, the satellite was able to send a hefty amount of data in a short period of time.

The entire collection of images captured so far by the HiRise camera can be viewed here.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.