Welcome to the Embassy of Satan! As Iran's Revolution Turns 35, Former U.S. Embassy In Tehran Remains Popular Rallying Point -- And Tourist Site

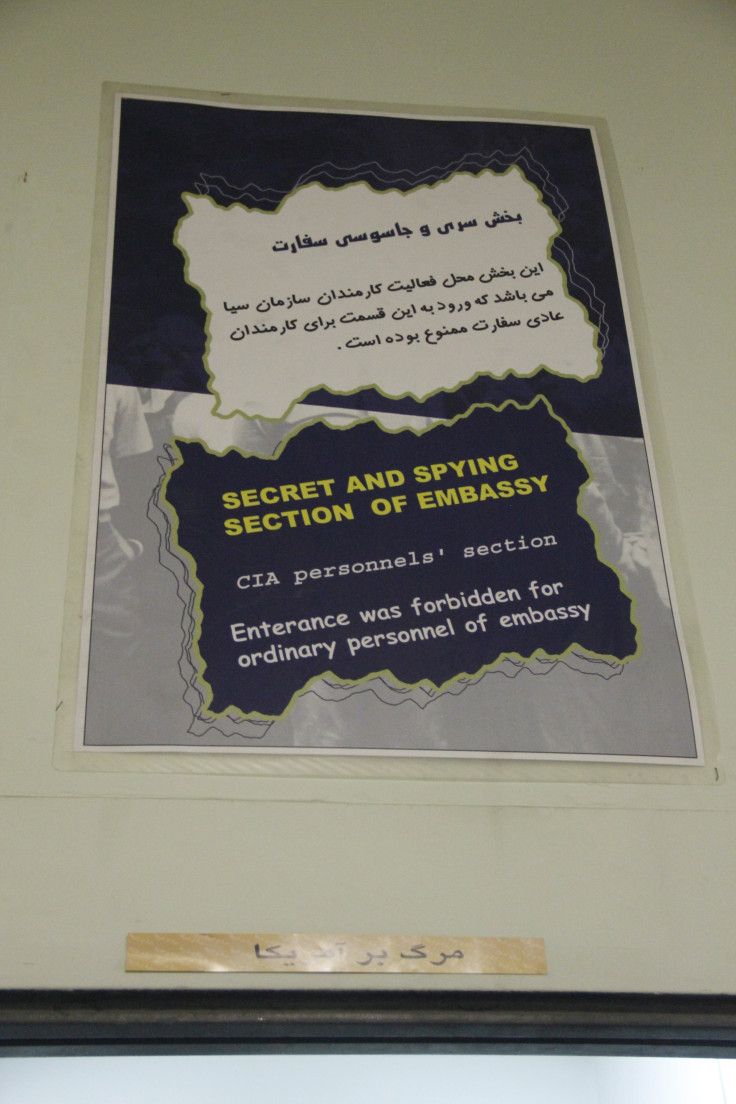

TEHRAN — In black chadors that cover them from head to toe, the women shuffle forth like a procession of nuns, occasionally whispering a few words and furtively taking snapshots with the reverence due a sacred place. They walk past defaced renderings of the Statue of Liberty, a favorite target for smear, her face portrayed as a malign-looking skull with a caption, “The disgusting empire of Satan.” Further on, there is a mock statue of the statue with her entrails revealing prison bars, photos of children who died in Middle East wars, and communications machines that look like props from the original TV series “Mission: Impossible.”

The guide is a tall, neatly dressed man of 29 with a trimmed beard, who asks not to be quoted by name. He confidently leads the group through corridors linked by armored doors with combination locks similar to those at bank vaults, separating one secure, claustrophobia-inducing room from another, furnished with curious appurtenances such as oddly shaped typewriters and computers from a lifetime ago.

All but two of the Iranians touring the former U.S. Embassy in Tehran were born after the popular revolt led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini toppled the last Shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, in 1979. The majority were born to a nation ruled by clerics and by Shariah, Islamic canonic law, where women cover their heads in public and all public statements begin with invocations of the grace of God. They are the children of the revolution that gave birth to the first Islamic Republic in history. For them, a nation ruled by clerics is as normal as instant messaging on the mobile phones they are fiddling with.

If calendars dictate the age we live in, then the Iran of imperial ancestry, theocratic rule and cell phones lives simultaneously in three separate eras. On March 21 it’s Norooz, or New Day, the start of year 1393 since the Hegira, prophet Mohammed’s journey from Mecca to Medina to escape a conspiracy to murder him. Iranians and Afghans go by the solar calendar, whereas most Muslim nations observe the lunar calendar, according to which it is 1435, also acknowledged in Iranian calendars and diaries.

For a couple of years, Iran was governed by the imperial calendar imposed by the last Shah, who in 1976 decreed that 1941, the year his reign began, was to become 2500, marking the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great. Thus, overnight, Iran leapt from the year 1355 to 2535. After the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the country promptly went back to 1357.

While the imperial calendar was a reflection of doomed megalomania, Iranians do not need it to remember that their nation's date of birth is shrouded in darkness, and subject to debate. Iran is one of the very few nations in the world, if not the only one other than China, with uninterrupted statehood punctuated by brief stints of occupations by foreign powers.

Unlike citizens of other former empires, including Japan – arguably the last country nominally ruled by an emperor – Iranians are unapologetic about and proud of their imperial tradition. Even the previous Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, as the head of the republic that deposed the last emperor, took offense at what he saw as deliberate misrepresentations of Iranian history in “300,” a Hollywood movie about the Battle of Thermopylae between Persians and Greeks in 480 B.C. In September 2007, as he was attending the U.N. Assembly in New York, Ahmadinejad said, according to The New Yorker: “When they can’t break our will” – he was referring to the United States – “they try to insult our history… That film claimed that under Darius the Great twenty-seven nations paid tribute to Iran… No, under Darius forty-two nations paid tribute to Iran!”

In a sense, Iran is still such an empire. Like other historical powers such as Russia and Turkey, it has retained imperial attributes – including geography and an ethnically diverse population – under the trappings of a republican order, a state that fought other nations and empires into demise millennia ago.

Nations like these call for monuments that lend them legitimacy, the architecture of might as right. The former U.S. Embassy in Tehran is to the Islamic Republic what the Gate of All Nations, built by Xerxes in the 5th century B.C., was to the Persian Empire. The embassy building in Iran stands as a trophy of the resistance of the ancient empire to the superpower of the day, a fitting birthmark of the Islamic Republic, as the revolution was borne of the tortuous relationship between the two nations.

A Coup, a Cleric and a War

The more distant origins of the events leading up to the Islamic Revolution and the U.S. Embassy takeover date back to the 1950s. The U.S. and Britain were the architects of the 1953 coup against the former prime minister of Iran, Mohammad Mosaddegh, who tried to nationalize the oil industry, which was essentially in British hands. Increasingly frustrated with Mosaddegh, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill convinced the Eisenhower administration that Iran was in danger of falling into the Soviet orbit, which prompted the White House to orchestrate the plot. CIA operative Kermit Roosevelt, grandson of former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, planned the conspiracy to topple Mosaddegh from the U.S. diplomatic headquarters in Tehran.

With the Shah’s secret consent, Mosaddegh was deposed in 1953, but the coup set the ground for radically overturning the order it was trying to prop up. For Iran, playing the role of a vassal in a world divided between two superpowers – the incarnation of empires in the 20th century – was an insult.

As often happens in dictatorial Muslim countries, political dissent that was stifled everywhere else shifted to unassailable space – the mosque – and found its most articulate proponent in an unsmiling cleric in the holy city of Qom, some 80 miles from Tehran. In 1964, Ayatollah Khomeini, who until a few years earlier had restricted his books to treatises on Shariah law and simple manuals on its daily-life applications, repudiated in a speech the agreement the Shah had made with the U.S. regarding diplomatic immunity for its military personnel.

“They have reduced the Iranian people to a level lower than that of an American dog,” Khomeini said (meaning, specifically, a dog owned by an American, though “dog” in conversational Farsi can also be employed as an insult). “If someone runs over a dog belonging to an American, he will be prosecuted… but if an American cook runs over the Shah, the head of state, no one will have the right to interfere with him.”

After his “American dog” speech, Khomeini was expelled from Iran. By then, he already had built a base of reverent followers among university students in Qom. What Khomeini may have lacked in depth in his blunt discourse was more than made up for by the enigmatic charisma of a man who avoided eye contact and frequently sought solitude.

After Iran was swept over by the Islamic Revolution, the U.S. maintained a skeletal staff of 60 at its embassy – compared with more than 1,000 previously – until simmering misgivings were exacerbated by the decision of the Carter administration to allow the exiled Shah to enter the U.S. for cancer treatment. Two weeks after the Shah arrived in New York, on Nov. 4, 1979, distrust turned into rage, when, to the cries of “Marg bar Amrika!” (“Death to America!”), thousands of demonstrators surrounded the U.S. Embassy, demanding that the Shah be handed over to the new Islamic government.

The mob soon overran the building and 52 U.S. diplomats were held hostage for 444 days, which many consider the nadir of the Carter presidency, in part because of a dramatic, failed rescue operation that resulted in the deaths of eight American servicemen and one Iranian civilian and the destruction of two American aircraft. The hostage episode ended after Iran, which had recently been attacked by Iraq, negotiated for the hostages’ release through the arbitration of the nation of Algeria. The hostage release was announced in January 1981, moments after U.S. President Ronald Reagan was sworn into office.

The hostage crisis set in motion successful U.S. efforts to impose economic sanctions on Iran which remain in place, and began 35 years of enmity between the two nations that has played out in multiple proxy wars in the Middle East, starting with the attack by the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein against Iran in 1980, with the open and tacit support of most world powers, including the U.S., intent on containing the unexpected fury of the Islamic Revolution. That war ended in 1988, with a truce mediated by the United Nations, which Khomeini accepted unhappily, comparing it to drinking “a cup of poison.” By then, the regime had firmly established itself, as Iranians had rallied around the government in the face of perceived aggression.

The Former Hostage

A man who identified himself as one of the former hostages visited the former U.S. Embassy on the latest anniversary of the takeover, on Nov. 4 of last year, though he didn’t disclose his name. “He was very old,” the guide of the former embassy – renamed “Den of Espionage” – says. “He looked like Steve Jobs; slender, but with white hair, rimless eyeglasses, and a very sad expression in his eyes, as if he had some profound disillusion,” he says, comparing him to Apple’s late founder.

According to the guide, the former hostage smiled briefly when he looked out into the compound’s courtyard from one of the few open windows on the floor and evoked the days when the embassy staff played volleyball. The guide’s guess is that he was from the intelligence communications department, as there appeared to be a spark of recognition when he saw the old machines displayed. The former hostage “touched the computers and the equipment, caressing the keyboards with a look of nostalgia.”

The Iranian guide pauses for a moment and surveys the room he has seen a thousand times. “We love the American people; we even supported the Occupy Wall Street,” he says. “It’s just the politics,” he adds, and goes on to explain in Farsi now, as we walk by radio communications systems and devices to tap telephone conversations, that this was the intelligence section floor, where the personnel of each department did not know who worked for the other divisions, only exchanging paper correspondence through mail slots in the safe doors. The Glass Room is a self-explanatory conference room for secure conversations and debriefings, now manned by three rather bizarre-looking mannequins wearing démodé suits, sitting around a table.

There are document incinerators and shredders that jammed when they were overfilled, the guide says, stroking one of the machines. “It is just like they showed in Argo!”, he says, in reference to the 2012 Ben Affleck movie about the escape of six U.S. diplomats who managed to flee the embassy and were harbored by the Canadian ambassador to Iran. “Just like in the movie, young people were able to piece together the torn pieces of paper,” the guide says, showing a book that features the reconstructed documents.

Monireh Sadat Jafari, a 22-year-old woman with the delicate poise of a tulip, is visiting the compound for the first time. She mans a stand at the House of Zahra, a religious learning institution, at an exhibition on the Quran in the backyard of the embassy. She is accompanied by Fatemeh Rahmipoor, 28, a Lur, an Iranian ethnic group, who has visited the former embassy several times. Monireh is snapping photos with her mobile phone, wearing half-finger black gloves on which the word “LOVE,” in English, is sewn in silver sequins.

Monireh beams when she is recognized as a descendant of Reza – the Eighth Imam in Twelver Shia Islam and among the more revered, martyred in 818 – indicated by her “Sadat” surname. “I know I am a real Shiite,” she says with a proud smile. Neither she nor Fatemeh remembers Khomeini and the revolution they were born into. They grew up surrounded by stories and sequels of the Iran-Iraq war they never experienced, which left 1 million dead between civilians and soldiers in a conflict that saw extensive use of chemical weapons and myriad other atrocities. Monireh’s father is a handicapped war veteran, as is Fatemeh’s brother, who joined the Basij militia, an armed formation of revolutionary volunteers, at the age of 9, and was promptly dispatched to the front along with thousands of other child soldiers. Fatemeh’s father-in-law fought in the war, too, and she lost two of her cousins in the battlefield.

“We never hear good things about the U.S. in school or anywhere,” Monireh says as we walk to the pavilion where the Quran exhibition is being held, on the former embassy grounds. “What I know is that Americans are nice but not their politicians, who are warmongers.” Fatemeh concurs, adding, “Our goal is to live as the Quran prescribes whereas the U.S. is a self-centered society, which pursues its selfish interests, all that is for its own benefits.” But she adds that she came to see the U.S. in a different light during her career at the Social Sciences Faculty, from which she graduated. “The U.S. is a developed country, and Social Sciences, as a Western product, says generally good things about the West generally… As humans, we are all equals, but…”

She can’t complete her idea, as an unshaven young man walks up briskly to the House of Zahra stand and interrupts her, speaking softly and staring at both of them. He tells them that they can discuss only Quranic matters and to steer clear of politics. Monireh pales and her lips seal into a tight, scared smile. A pall of fear has descended into her large, mellow eyes, and very discreetly she takes her “LOVE” gloves off. Fatemeh reacts with the jaded, tired grin of someone who is familiar with this situation. Monireh stands up, saying she is going to fetch her mother, a school principal who is elsewhere at the exhibition hall. She doesn’t come back.

Friday Prayers

Hossein Pour Abbas remembers as clear as day the takeover of the embassy. He was dispatched two days after the takeover, on Nov. 6, 1979, to guard the compound as part of the militias who patrolled its perimeter. “Before the revolution, I didn’t care about politics, until Imam Khomeini came and opened our eyes,” he says. Soon after, he joined the Basij militia. It is Friday, the week’s holy day in Islam. If the former U.S. Embassy marks the revolution’s baptism of fire, Tehran’s Mosalla – a sprawling religious complex that includes construction in progress – is a monument to its victory. The enormous, stark, concrete minarets are an unintended example of brutalism in the architecture of faith at the half-completed site. Shaped like rockets about to take off, they tower above the Mosalla and its stadium-sized hall where Friday Prayers are held. Tehran’s Friday Prayers are a major event in Iran, during which senior clerics deliver sermons that convey the religious establishment’s views on major national and international issues.

Across the esplanade outside the prayer hall, a group of handicapped men is being wheeled past security checkpoints into a tent where they will undergo special inspection. They are Iraq war veterans, including Abbas, 52, who lost his legs during a mortar attack in the Khoramshahr area, near the Iraqi border in southern Iran, in 1980. “I just heard the hissing sound of the projectile when it was only two yards away. There was nothing I could do,” he says, with an amiable smile, in the characteristic Iranian melodious lilt. The blast severed his right leg instantly and his other limb was amputated afterwards.

After he was injured, another handicapped war veteran introduced him to the woman he married, with whom he had three children, all of them university graduates. “At the time, every Iranian woman wanted to marry soldiers,” he says. Looking back, would he have done anything differently? “If I could go back in time and become a young man again, I would go to war again to defend Iran and Islam,” he says. His gentle, musical voice – in contrast with his life experiences -- conveys a feeling of plenitude, of a man who is at peace with himself.

Cries of “Marg bar Amrika!” (“Death to America!”) come from the prayer hall. A man holding a prosthesis of a left arm and shoulder walks away from the veteran checkup tent, with a grim look in his face. Why are the veterans subjected to body inspections? “A veteran tried to introduce bombs hidden in his wheelchair a couple of years ago,” Abbas explains.

Inside the prayer hall, Ayatollah Sayyid Ahmad Khatami, a conservative member of the Assembly of Experts – one of the religious ruling bodies of Iran, charged with electing Iran’s Supreme Leader, who holds more power than the democratically elected president – is decrying U.S. President Barack Obama. “What Obama said about Iran shows that we are right to follow the third path of Imam Khomeini,” he says. He is talking about Obama’s reference to Iran in his State of the Union message, in which he credited sanctions and diplomacy for preventing Iran from acquiring an atomic bomb.

“How dare Obama say in his speech that the Geneva deal has stopped Iran from achieving the atomic bomb when our Supreme Leader didn’t speak about seeking a bomb?” asked Khatami, who is no relation to former reformist Iranian President Mohammad Khatami. “You Americans bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki after Japan was all but defeated; Hitler had committed suicide and Mussolini had been hanged.”

“Down with America!” he exclaims from the pulpit, a balcony decorated in intricate arabesque patterns in the tradition of Iranian mosque tiles, radiating a polychromy of turquoises, blues and white. A massive chorus of voices responds with the ritual cries of “Death to America, Israel, England, the double-faced!” Yet on closer inspection one could see the fists were mostly going up just in the first row and there was tepid fervor in the crowd. Most attendees were men with balding heads and gray hair. The younger faces were mostly those of groups of soldiers and students bussed in – including a group of children in martial arts uniforms, enjoying the moment as they would a match, who were reciting the lines as mechanically as prayers learned a long time ago. Something about the ceremony felt staged and anachronistic, with an echo of the calcified rituals of the tired Communist parades in the Soviet Union of the later days.

More subtly, yet perhaps more importantly, there was an inflection in the voice of Ayatollah Khatami when he was faulting Obama for disbelieving Iranian intentions about nuclear weapons. The change in Khatami’s tone was subtle, yet noticeable, in the careful wording and the lowered volume. It had the markers of a perfunctory statement. More to the point, the Supreme Leader has not said that Iran was seeking the bomb, as Ayatollah Khatami proclaimed. However, he has not said that Iran is not seeking it, either.

Not for nothing Iran is the country of “taarof,” an untranslatable concept that indicates the widespread etiquette, cultivated over millennia, of highly adorned speech, by which it is rude among Iranians to express intention in a straightforward manner, often including a cab driver’s elusive answers about the fare, with responses such as “Money doesn’t matter; life is transient” and other philosophical musings like it in the chaotic traffic of Tehran. It is also the country of “ketman” or “taqqiya,” terms used interchangeably to denote in Islam a form of religious dissimulation or concealment of personal opinions in adverse circumstances, showing outside conformity while disguising private opposition.

When asked whether there was an element of taqiyya in Iranians' public statements about their nuclear program, an émigré Iranian businessman smiles cunningly and responds with a Persian parable, in the best tradition of taarof: “A child is refusing to say ‘alef,’ the first letter of the alphabet. His teacher beats him, but to no avail. He will not say it. Puzzled, the teacher asks the child why he is refusing. ‘Because if I say 'aleph,' then I will have to say 'be,' 'sin' and 'gin,' and then recite all the alphabet to the end.’”

In other words, once you start, there is no stopping, and no going back.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.