1,500-Year-Old Teeth From German Plague Victims Reveal ‘Repeated Emergence’ Of Deadly Yersinia Pestis Bacteria

Scientists are finding clues about the origin and spread of centuries-old European plagues from the most unusual of places: the dental records of long-forgotten plague victims. Teeth from two casualties of the Plague of Justinian, which tore across the Eastern Roman Empire during the 6th century AD, killing as many as 25 million people worldwide, are revealing links between the Justinian plague and other deadly pandemics in human history.

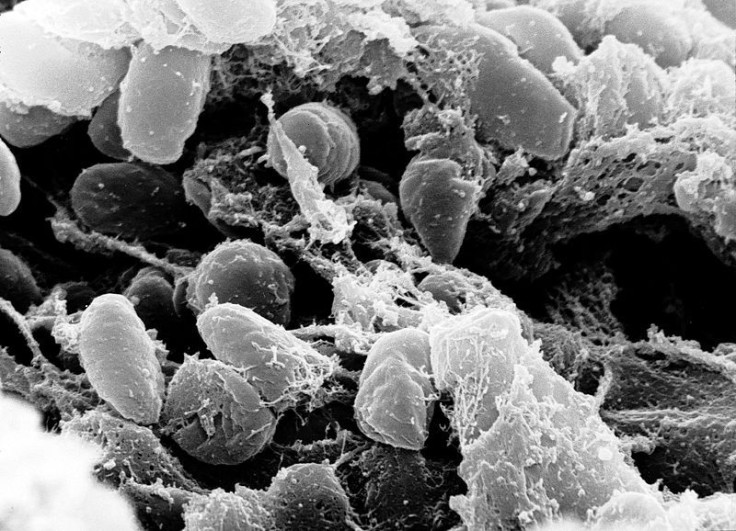

According to scientists from the McMaster University in Canada, the bacterium that caused the Plague of Justinian came from the same pathogen that would later cause the Black Death pandemic in Europe. Both plagues originated from the Yersinia pestis bacterium, first discovered in the late 19th century by a physician from the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

Researchers came to this conclusion after extracting and analyzing bits of DNA from 1,500-year-old teeth, pulled from the remains of two victims buried in Bavaria, Germany, following the deadly Plague of Justinian. By reconstructing the genome of the bacteria found in the 6th-century teeth, researchers discovered that the strain that led to the Justinian plague seems to have gone extinct or is dormant, possibly “unsampled,” or hiding, in rodent populations around the world.

“What this shows is that the plague jumped into humans on several different occasions and has gone on a rampage,” Tom Gilbert, a professor at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, told the Associated Press. “That shows the jump is not that difficult to make and wasn’t a wild fluke.”

The results of the study, published in online version of the journal Lancet Infectious Diseases, suggest that the strain of Yersinia pestis behind the Justinian plague was distinct from the strain responsible for the Black Death, which killed 75 to 200 million people in mid-14th century Europe.

"The strains of Y. pestis in the Plague of Justinian form a novel branch on the Y. pestis phylogeny," the authors wrote.

This means that, while the Justinian plague was certainly an ancestor of the Black Death, it was not the same thing. According to the Los Angeles Times, the main differences between the Justinian outbreak and the Black Death pandemic 800 years later is associated with the bacterium’s ability to spread and kill its host. In fact, the Justinian strain appeared deadlier than the plague that would follow it.

“We know the bacterium Y. pestis has jumped from rodents into humans throughout history, and rodent reservoirs of plague still exist today in many parts of the world," Dave Wagner, an associate professor in the Center for Microbial Genetics and Genomics at Northern Arizona University, told AFP. "If the Justinian plague could erupt in the human population, cause a massive pandemic, and then die out, it suggests it could happen again."

But don’t worry: Wagner said current antibiotics can combat the plague and would lessen the chance of another large-scale plague pandemic. Every year, there are several thousand cases of plague around the world, mostly in central and Eastern Europe, Africa, Asia and parts of the Americas. The last major outbreak of plague in the U.S. occurred in Los Angeles in 1924 and 1925, when flea-infested rodents arrived on steamships from Asia.

"Plague is something that will continue to happen but modern-day antibiotics should be able to stop it," Hendrik Poinar, research leader and director of the Ancient DNA Center at McMaster University in Canada, told the Associated Press. "If we happen to see a massive die-off of rodents somewhere with [the plague], then it would become alarming.”

Previous research has implicated Yersinia pestis as the cause of two recent pandemics – the Black Death and another outbreak in the late-19th and early-20th centuries – but the origin of the pathogen that led to the Justinian plague was up for debate.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.