A 430,000-Year-Old Human Skull With Lethal Wounds Linked To Prehistoric Murder

Scientists have discovered lethal wounds on a fossilized human skull, which could offer evidence of one of the first cases of murder in human history nearly 430,000 years ago. The discovery shows that deadly interpersonal violence is an "ancient human behavior," scientists said in a study, published in the journal PLOS One on Wednesday.

The skull, which was believed to be of a primitive member of the Neanderthal lineage, was found at an archeological site of the Sima de los Huesos, which means the “Pit of the Bones,” in northern Spain. The site is located deep within an underground cave and contains the skeletal remains of at least 28 early humans, who might have existed during the Middle Pleistocene time period.

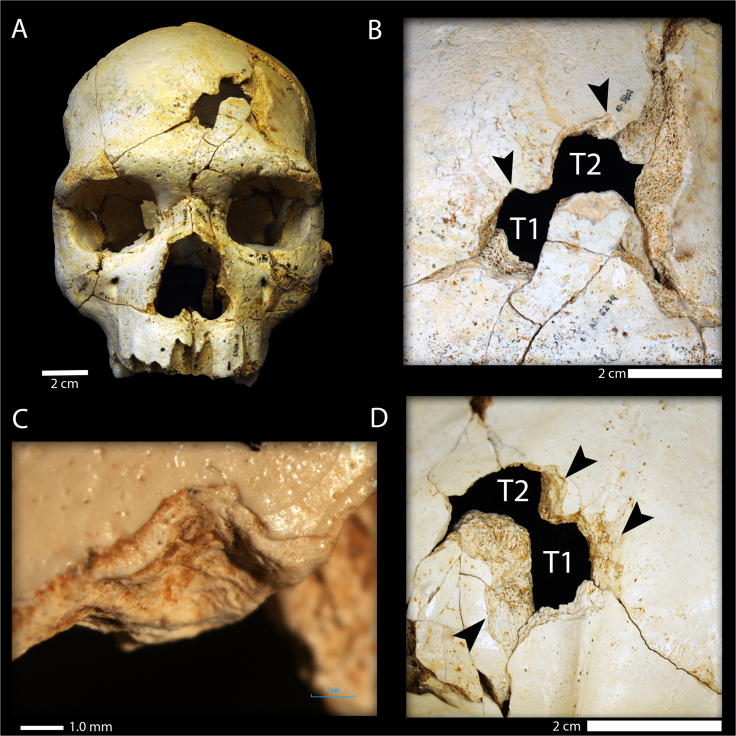

“Evidence for interpersonal violence in the human fossil record is relatively scarce, and this would appear to represent the coldest cold case on record,” Rolf Quam, an anthropologist in New York's Binghamton University, said in a statement, referring to the ancient skull, which shows two penetrating wounds on the frontal bone, above the left eye.

As part of the study, the scientists used modern forensic techniques to determine that both fractures on the skull were inflicted by two separate impacts using the same object, but “with slightly different trajectories around the time of the individual’s death.”

Researchers said that the type of the fractures, their location and the possible involvement of a single weapon to deliver the blows suggest that the injuries are unlikely to be the outcome of an accidental fall down a vertical shaft, but the result of an act of fatal interpersonal aggression.

“This individual was killed in an act of lethal interpersonal violence, providing a window into an often-invisible aspect of the social life of our human ancestors,” Nohemi Sala of Madrid's Centro Mixto UCM-ISCIII de Evolución y Comportamiento Humano, and the study’s co-author, told Reuters.

The only access to the site, where the skull and other human skeletal remains were found, was through a nearly 43-foot deep vertical shaft. Scientists believe that the individuals were already dead before other humans likely carried them to the bottom of the vertical shaft, indicating an early evidence of funerary behavior.

“This is really good evidence for an intentional role for humans in the accumulation of bodies at the bottom of this pit and suggests the hominins from this time period were already engaging in complex cognitive behaviors,” Quam said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.