Alaska’s Chinook Salmons’ Birth, Migration History Revealed By Chemical Tags In Ear Bones

Scientists have identified a chemical signature on the ear bones of Chinook salmon from Alaska’s Bristol Bay region, which helps track the fish’s birth and migration history. In a study, published in the journal Science Advances last week, scientists said that the new findings could tell them where the fish are born and how they spend their first year of life.

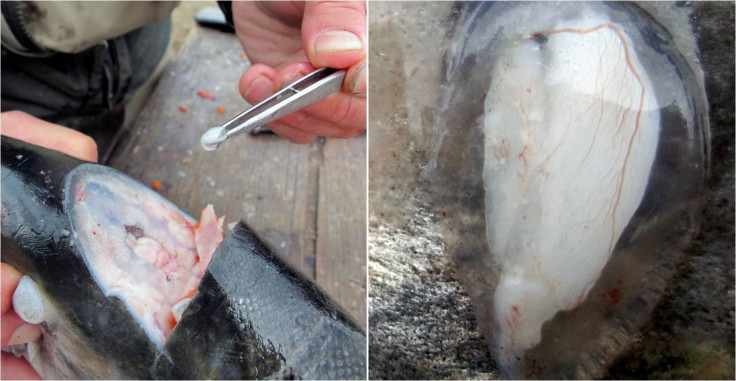

The ear bone, called “otolith,” builds up layers throughout a salmon’s life. Scientists can tell where the fish lived by comparing the chemical signatures of the otolith with those of the water in which it swims. The chemical signature originates from isotopes of strontium, which is found in bedrock. As rushing water comes through the rocks, strontium is dissolved and released into the water. After the dissolved element gets picked up by fish, its ions are deposited onto the otolith, according to the scientists.

“Each fish has this little recorder, and we can reveal the whole life history of the fish from the perspective of the otolith,” Sean Brennan, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, and the study’s lead author, said in a statement. “Each growth ring is a direct reflection of the environment the fish was swimming in at the time it was formed.”

Even after it makes its way from rocks into the otoliths of salmons, the chemical signature remains unchanged, serving as a strong tag that can reveal a fish’s specific location in the river at a specific time.

The study was carried out in the Nushagak River, which hosts about 200,000 Chinook salmons each summer. The fish come from the ocean to spawn in the river’s upper tributaries and streams, and when their eggs hatch in the spring, young Chinook salmons spend the first year of their life in the river, feeding and growing before they migrate to the Bering Sea and the Pacific Ocean.

“This is science responding to a societal issue and need,” Christian Zimmerman, an ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, and the study’s co-author, said in the statement. “Using this approach, we will be able to map salmon productivity and determine how freshwater habitats influence the ultimate number of salmon.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.