An Alien World On Earth: Mexican Underwater Caves Home To Methane-Fueled Ecosystem

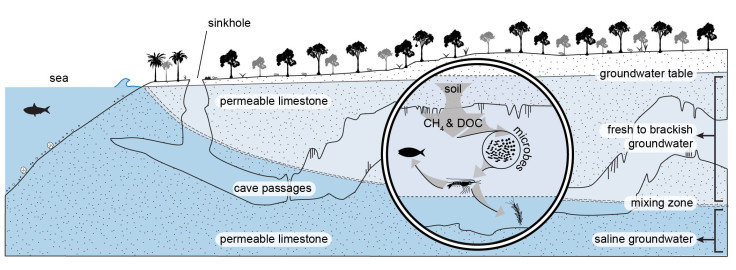

The underground rivers in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, located inside underwater caves, are very unusual in more ways than one. For one, they have two distinct layers of water, one fresh and the other salty, making it look almost like a river within a river. Of course, there is also the fact that there exists in these shallow depths a methane-fueled ecosystem that is otherwise found only in the deep ocean.

Researchers from the United States Geological Survey, Texas A&M University at Galveston, and their collaborators from Mexico, the Netherlands, Switzerland and other U.S. institutions, recently studied a cave network in northeastern Yucatan and found “methane and the bacteria that feed off it forms the lynchpin of an ecosystem that is similar to what has been found in deep ocean cold seeps and some lakes,” according to a USGS statement Tuesday, which also called the system a “cryptic world.”

The Ox Bel Ha cave network studied for the paper, published Tuesday by the researchers, has a layer of freshwater that accumulates due to rainfall and another layer, with a different density, of saltwater that is brought in by the ocean outside. The methane in the caves forms naturally beneath the forest floor nearby. Normally, the gas produced in the soul travels upward, into the atmosphere, but in this case, it migrates downward, deeper into the caves and the water.

Bacteria and other microbes that live in the caves, and form the basis of the local ecosystem, feed off the methane and other organic material carried in by freshwater from the top. Larger organisms, such as a cave-adapted shrimp species, feed off these methanotrophic microbes. This particular shrimp species gets as much as 21 percent of its total diet from methane-eating microbes, in fact, the study found.

“Fatty acid and bulk stable carbon isotope values of cave-adapted shrimp suggest that carbon from methanotrophic bacteria comprises 21% of their diet, on average. These findings reveal a heretofore unrecognized subterranean methane sink and contribute to our understanding of the carbon cycle and ecosystem function of karst subterranean estuaries,” the study said.

David Brankovits, the paper’s lead author who conducted the research during his Ph.D. studies at Texas A&M, said in the statement: “Finding that methane and other forms of mostly invisible dissolved organic matter are the foundation of the food web in these caves explains why cave-adapted animals are able to thrive in the water column in a habitat without visible evidence of food.”

The mechanism of how organisms in such cave ecosystems accessed organic food material was poorly understood till now, with a common assumption being it got there from vegetation and other organic material that made its way into the caves via the sinkholes. But very little debris was found inside the caves.

Scientists involved in the research were also trained in diving, given the nature of the research. The cave system is always underwater, and techniques usually used for studying deep-sea environment by submergence vehicles had to be employed in Yucatan too.

“The processes we are investigating in these stratified groundwater systems are analogous to what is happening in the global ocean, especially in oxygen minimum zones where deoxygenation is a growing concern. Although accessing these systems requires specialized training and strict adherence to cave diving safety protocols, relative to the complexity of an oceanographic expedition, the field programs we organize are simple and economical,” John Pohlman, a co-author of the study and a USGS biogeochemist whose work from the early 90s motivated the research, said in the statement.

Titled “Methane- and dissolved organic carbon-fueled microbial loop supports a tropical subterranean estuary ecosystem,” the open-access paper appeared Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.