Arctic Drilling 2015: Shell Advances Plans To Drill In The Alaskan Arctic Despite Low Oil Prices, Environmental Concerns

Royal Dutch Shell PLC is pushing ahead with a controversial plan to drill for oil in the Alaskan Arctic, despite the recent plunge in oil prices that has forced companies to cut thousands of jobs and slash spending plans for exploration. For Shell, the Alaskan venture still makes financial sense in an era of cheap oil because the project is part of its long-term energy strategy, analysts say.

“Today’s oil price is less relevant to them, other than the fact that it influences how many of these projects they can do,” said Dennis Cassidy, a managing director at AlixPartners, a global consulting firm, and co-head of the oil, gas and chemicals practice. If all goes according to plan for Shell, he said, “Twenty years from now, when [the project is] ready to go full-scale commercial, they’ll have the technology and capability to produce it and make a full return on investment.”

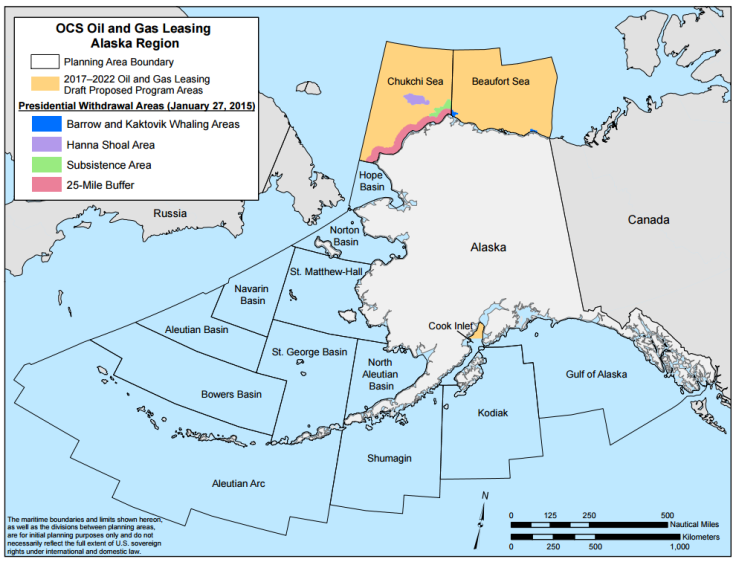

Shell this week came one step closer to tapping reserves in Alaska’s far northern Chukchi Sea after the Obama administration gave Shell conditional approval to drill in the icy waters. The U.S. Interior Department will give its final approval after Shell receives the remaining state and federal drilling permits for the project, including authorizations under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and permits from the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, officials said. If the process goes smoothly, Shell could begin drilling this summer, although the first barrels of oil won’t likely hit the global market for at least a decade after the initial wells are tapped.

Brent crude, a global benchmark, and U.S. crude are both down by about 40 percent compared with their peaks in June 2014, when Brent traded for $112 a barrel and U.S. crude for $105 a barrel.

After Shell’s mishaps, ConocoPhillips and the Norwegian oil giant Statoil ASA suspended their plans to drill in the Alaskan Arctic. The Obama administration also developed the first federal offshore drilling standards for the Chukchi and Beaufort seas, which the White House approved in February. Still, officials are helping to open more parts of Alaska’s waters to drilling. In January, the Interior Department proposed to offer three new leases for Arctic oil and gas drilling, as well as leases in the Gulf of Mexico and, for the first time, along the Atlantic Coast.

Shell has already invested $6 billion in its Alaska drilling program. If the Anglo-Dutch energy giant can successfully extract oil from the region, the payoff could be a huge boon for the company’s revenue in particular and U.S. energy production in general. Shell’s lease for federal Arctic waters is estimated to hold 4.3 billion barrels of recoverable oil, according to the Interior Department’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, which sold Shell a $2 billion lease in 2008. Federal scientists say the entire region could hold as many as 15 billion barrels of oil.

By comparison, the entire state of North Dakota -- the epicenter of America’s shale drilling boom -- has about 7.4 billion barrels of recoverable oil, the U.S. Geological Survey estimates. Alaskan oil development “could cause a huge increase in U.S. supply,” said Brian Scheid, the senior editor of oil news for Platts, an energy information service. Among major oil companies, “there’s always this race to the best plays -- of who can be the first producer to stake its claim in those waters before anybody else,” he said. “But there are still big questions over how it can be developed.”

The Chukchi Sea is extremely remote and prone to icy waters, major storms and waves that can reach 50 feet high. In the event of a spill or accident, the closest Coast Guard resource with the necessary equipment is more than 1,000 miles away. The stretch of Alaskan coast near the drilling area has no roads leading to major cities or ports for hundreds of miles. And the window for drilling is extremely narrow: just a few months during the summer. If federal officials delay Shell’s approval this year, the company would have to wait to drill until the summer of 2016 at the earliest, Scheid noted.

Shell is also banking on the fact that, once the wells are drilled, the cost of actually producing the oil will be economically viable in coming decades. “Part of this is making a leap of faith that science and technology will catch up with your ability to explore and find where the good rocks are,” AlixPartners’ Cassidy said.

For energy giants like Shell, pursuing risky ventures in areas such as the Alaskan Arctic is key to growing their market share, said David Elmes, who heads the Warwick Business School’s Global Energy Research Network in England. “They are very large companies, and so to move the needle in terms of their performance, they have to think of large-build projects that will change the industry over quite a long length of time,” he said.

Elmes said that in recent decades oil majors such as Shell, BP, the Exxon Mobil Corp. and the Chevron Corp. have faced increasing competition from national oil and gas companies, such as the Saudi Arabian Oil Co., and oil-field services firms, such as the Halliburton Co. and Schlumberger Ltd. As a result, the oil and gas giants are investing more in projects where other companies don’t have the budgets or technical expertise to compete. He pointed to Shell’s $70 billion bid for BG Group PLC, a liquefied natural gas company, and recent investments in gas-to-liquids technologies as examples of such a trend.

“Shell’s under pressure to identify what are the big new bets and to prove that they’re the only people who can actually take them on,” Elmes said. “They need big projects to demonstrate their competitive advantage in the industry.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.