Are Dark Matter, Dark Energy Real? New Theory Of Gravity Says No

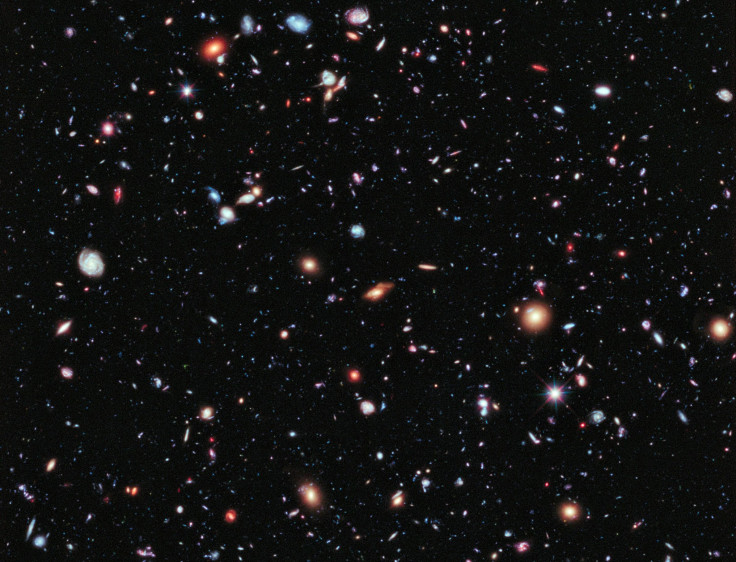

The hunt for dark matter and dark energy — the mysterious stuff that scientists believe make up 95 percent of the universe — has so far been fruitless. But what if this is because dark matter and energy don’t really exist?

This is what Erik Verlinde — a string theorist at the University of Amsterdam and the Delta Institute for Theoretical Physics — posits. In a newly published research paper, Verlinde argues that anomalies in the motion of stars and galaxies — the reason why scientists invoked the presence of dark matter in the first place — can be explained solely through a theory known as “emergent gravity.”

According to this theory, gravity, far from being a fundamental force of nature, is a phenomenon that “emerges” due to the movement of fundamental bits of information stored in the very structure of space-time. This movement changes the entropy — loosely defined as the degree of disorder or randomness of the universe — within that region of space-time, creating a force that acts like gravity.

In the paper, which is available on the preprint server ArXiv.org, Verlinde demonstrated how his theory of gravity accurately predicts the velocities at which stars rotate around the center of the Milky Way, as well as the motion of stars inside other galaxies.

“We have evidence that this new view of gravity actually agrees with the observations,” Verlinde said in a statement. “At large scales, it seems, gravity just doesn’t behave the way Einstein’s theory predicts.”

Einstein’s theory of general relativity tells us that gravity is the result of space-time being warped by the mass of celestial objects. While this theory — its predictions have been verified and observed empirically several times over the past century — works very well in explaining the macroscopic nature of reality, it runs into trouble when we use it to try and understand the behavior of subatomic particles — a realm governed by the laws of quantum mechanics.

One of the biggest extant challenges for theoretical physicists is reconciling relativity with quantum mechanics, and creating, in the process, what has long been known as a “theory of everything.” Verlinde’s theory of entropic gravity, in addition to removing the need for the mysterious dark matter, could also bridge the gap between the two most important theories of 20th century physics.

“Many theoretical physicists like me are working on a revision of the theory, and some major advancements have been made,” Verlinde said. “We might be standing on the brink of a new scientific revolution that will radically change our views on the very nature of space, time and gravity.”

However, it is important to note that Verlinde’s theory still has substantial limitations, as it requires imposing inexplicable constraints to the entropy of a system to match observations, and because it can’t yet be used to explain clustering of galaxies.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.