Argentina Fails To Reach Debt Agreement, Default Looms

(Reuters) - Argentina failed to strike a deal to avert its second default in more than 12 years after talks with holdout creditors ended without a settlement on Wednesday.

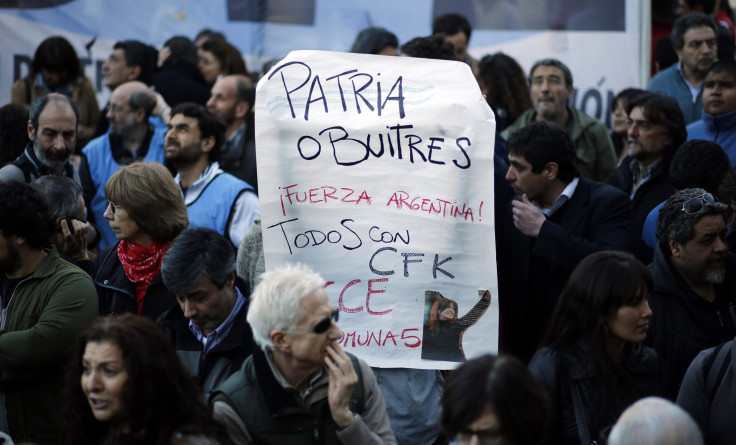

The country's economy minister, Axel Kicillof, speaking at a news conference at the Argentine consulate in New York, repeatedly referred to the holdout hedge funds as "vultures" after two days of talks failed to produce an agreement.

"Unfortunately, no agreement was reached and the Republic of Argentina will imminently be in default," Daniel Pollack, the court-appointed mediator in the case, said in a statement on Wednesday evening.

Kicillof said Argentina offered the holdouts similar terms as other creditors who recently negotiated with the country as it attempts to regain the good graces of international capital markets that it has been frozen out of since its default. Those terms were rejected, Kicillof said.

After defaulting in 2002, Argentina restructured its debt in 2005 and 2010. More than 90 percent of the bondholders agreed to accept new bonds with reduced payments. The holdouts refused the terms, and were awarded $1.33 billion, plus interest, by a U.S. judge.

A fresh default is not expected to affect Argentina's economy as it did more than a decade ago, when dozens were killed in street protests and the authorities froze savers' accounts to halt a run on the banks.

There will still be consequences, however, as it is expected to worsen an economy already in recession, weaken the currency as more Argentines seek to hold dollars, and put pressure on foreign reserves. It could also raise soybean prices, as the country is the world's third-largest soybean exporter.

"The full consequences of default are not predictable, but they certainly are not positive," Pollack said.

He said he planned to return to Argentina after the news conference, saying the country will take all measures needed to face what he called an unfair situation.

The minister reiterated the country's position - that it cannot pay the holdout hedge funds without triggering a clause that would cause it to renegotiate with bondholders who accepted restructured debt agreements after the country defaulted in 2002.

The holdout hedge funds want full repayment on bonds they bought on the cheap after the country defaulted, a demand Argentina has so far rejected.

Latin America's No. 3 economy has for years fought NML Capital, a unit of Elliott Management Corp, and Aurelius Capital Management, the leading U.S. hedge funds that rejected large writedowns.

The Buenos Aires government has pushed hard for a stay of the U.S. court ruling that set Wednesday's deadline.

The country has until midnight Wednesday (0400 GMT on Thursday) to break the deadlock. U.S. District Judge Thomas Griesa in New York was set to prevent Argentina from making the July 30 deadline - representing the end of a 30-day grace period - for a coupon payment on exchanged bonds.

Argentina has consistently argued that a so-called rights upon future offers, or RUFO, clause prohibits it from settling with the holdouts. That clause expires at the end of 2014.

Kicillof said Argentina has already made that payment, as it deposited $539 million in the Buenos Aires account of trustee agent Bank of New York Mellon. As of Tuesday, that money was still there, according to a source at the Argentine central bank.

U.S. ratings agency Standard & Poor's downgraded the country's long- and short-term foreign currency credit rating to "selective default," from triple-C-minus and C, respectively. S&P cited Argentina's failure to make a June 30 coupon payment on its discount bonds due in 2033, which it does not rate. The default rating will remain until Argentina makes a payment, the agency said.

"The making of the payment is not an automatic process - it takes time for that to happen," said Roberto Sifon-Arevalo, managing director at S&P.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.