Arsenal News: After Gunners’ Wage Bill Exceeds Chelsea’s, Is More Success On The Way To The Emirates?

The financial landscape in the English Premier League is shifting. In recent years the competition has been transformed by the unparalleled spending of multi-billionaire owners, chiefly Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich at Chelsea and member of Abu Dhabi’s ruling family Sheikh Mansour al-Nahyan at Manchester City. But the revelation that one of the league’s traditional, much more modestly run powers, Arsenal, now has a higher wage bill than Chelsea's, as reported by the Telegraph, further points toward a leveling of the playing field.

Since flying into Chelsea in 2003, Abramovich has spent in excess of £2 billion ($3.3 billion) on improving the club both on and off the pitch. For his investment Abramovich has garnered 11 major trophies -- more than the total of their previous 98 years of existence -- including three Premier League titles and, most pleasingly to the owner, the Champions League in 2012. Five years after Abramovich changed the face of English soccer, Sheikh Mansour upped the ante. Making an immediate impact when taking over a club known primarily for its propensity to shoot itself in the foot, his massive wave of spending led to a first major trophy in 35 years and made them Premier League champions in two of the last three seasons, at a cost of around £1.2 billion ($2 billion).

Abramovich’s first season was marked by Chelsea’s rival across London, Arsenal, becoming only the second team in history to win England’s top division without losing a game. That they have not won the title since is no coincidence. Suddenly Arsenal were struggling to compete to sign the elite players, while, even more worrying, having their best players poached by the nouveau riches. The loss of defensive star Ashley Cole to Chelsea in 2006 and then a string of talent leaving Arsenal for Manchester City -- including French-born players Samir Nasri and Gael Clichy -- only emphasized that Arsenal, one of the great names of English soccer, couldn't compete financially or on the field. A move to a new stadium at Ashburton Grove in 2006 only exacerbated its struggles, as repayments on the stadium further curtailed its spending.

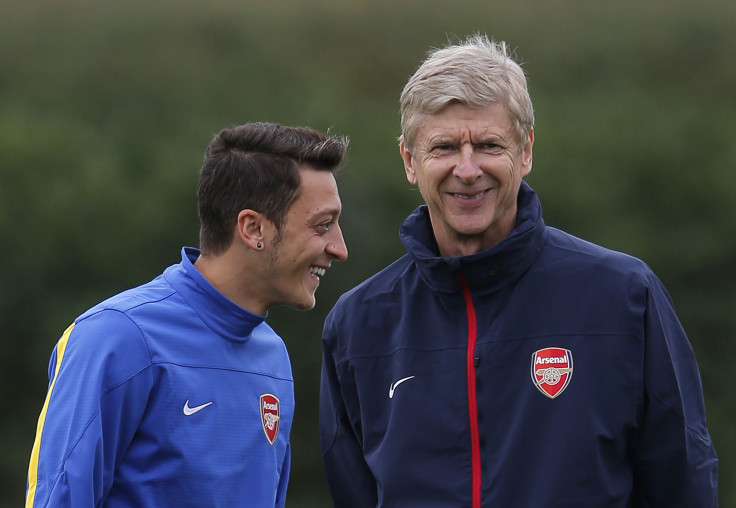

The club regularly stressed the need to spend within its means, while famed manager Arsène Wenger lambasted the “financial doping” of its newly flush rivals. Still, fans, more concerned with wins than spreadsheets, grew frustrated. After seven trophies in the previous 80 years, nine years went by without further silverware. But Arsenal’s lifting of the FA Cup in May to finally end that drought signals change.

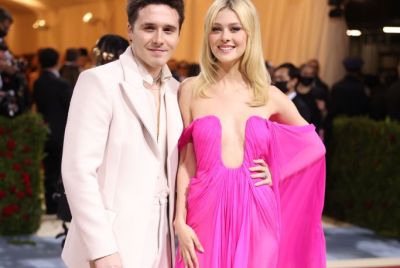

As Arsenal’s finances improved, thanks to the repayments on their stadium decreasing coupled with increasing revenue from commercial deals -- such as a new kit agreement with Puma -- and from the Premier League’s new television deal, the club now has significant money to spend again. In 2013, it almost tripled its previous record transfer fee by bringing in German superstar Mesut Özil from Real Madrid for £42.5 million ($69.4 million). As well as crucially now avoiding losing its best players, this summer a further outlay of around £75 million ($123 million) followed.

Just as significantly is that, according to the Telegraph’s figures, the latest arrivals take Arsenal’s wage bill over £180 million ($294 million), and in excess of Chelsea’s. Such a scenario would have been unthinkable just a few years ago. At the same time, another of England’s established powers run as a business rather than an indulgence, Manchester United, saw its wage bill grow to £215 million ($351 million) over the past year. And, after a massive summer of spending, that figure is likely to get even closer to Manchester City’s Premier-League leading £233 million ($381 million). The traditional powerhouses with their existing strong fan bases and infrastructure are now coming back to the fore in terms of spending. It is clear that Financial Fair Play (FFP) is making its impact felt.

Initiated by UEFA in 2011 and later the Premier League to prevent clubs from spending beyond their means, even if funded by a benefactor, FFP has quelled the carefree spending of Chelsea and Manchester City. Both clubs will still challenge for the game’s biggest honors having made their initial splurges just in time, but the established order in English and European soccer is now set to be preserved and, especially in England with its manner of distributing revenue from television deals, equality enhanced. And that is good news for Arsenal.

“I would say that the balance of power is a bit more even than it was five or six years ago,” Wenger said in August. “With the financial fair play added to the fact we have more financial power than five years ago, it gives us a better chance.” Arsenal’s move to their new stadium, while initially painful, is now bearing the long-term benefits. In terms of match-day revenue, its £93 million ($152 million) -- for 2012-2013, is some way ahead of Manchester City’s £40 million ($65 million), and even Chelsea’s £71 million ($116 million), according to figures released by Deloitte. In terms of commercial revenue, though, Arsenal still languishes some way back. Indeed, their earnings are less than half those of Manchester United’s.

Still Arsenal’s finances are undoubtedly healthy, as illustrated by their £208 million ($340 million) in cash reserves, easily the most in the Premier League. That figure is somewhat misleading, with Arsenal’s summer transfer spending not yet accounted for and £35 million ($57 million) going toward debt repayment on the Emirates Stadium. As financial blogger Swiss Ramble points out, the real amount available to spend on transfers is likely to be nearer between £40 million ($65 million) and £50 million ($82 million).

Nevertheless, the available resources coupled with Arsenal’s wage bill having now eclipsed Chelsea’s is entitled to leave fans wondering why the club’s squad is noticeably short of quality and quantity in key areas, especially in comparison to its rivals. In continuing to qualify for the money-spinning Champions League, Wenger, an owner of a degree in economics, has guided Arsenal through the troubled waters of a stadium move and its rivals welcoming of billionaires, but the barriers to the club’s success on the pitch now increasingly rest with him.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.