Obama's Overseas Corruption Busting Efforts Target Corporations, Executives

When German engineering giant Siemens AG in 2008 agreed to pay $1.6 billion to settle lawsuits accusing it of bribing Argentine officials to land a lucrative government contract, there was a question raised about the lack of any names of people on the defendant list.

Someone had to have disguised bribe money as consulting fees in a government-kickback scheme that also targeted officials in Iraq, Venezuela and Bangladesh.

Three years later, on Dec. 13, the U.S. Department of Justice rolled out indictments on eight former executives and agents of the Munich-based corporation and its Argentina subsidiary--seven of which were also hit with a Securities and Exchange Commission action.

Siemens and its senior executives were charged under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a Watergate-era anti-corruption law prohibiting companies based in the U.S. or listed on a U.S. stock exchange from bribing officials in other countries.

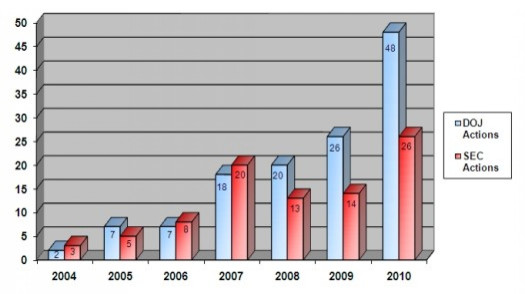

Prosecutors have been enforcing the FCPA aggressively for several years, hitting a peak of 48 lawsuits in 2010. Now the U.S. Chamber of Commerce is leading the effort to narrow the scope of the law.

For Obama administration critics who lament the lack of indictments against actual people for corporate malfeasance in the run up to the financial meltdown, they may find some solace in the Justice Department's dogged FCPA prosecution efforts in 2009 and 2010, which saw more than 50 corporate officers and employees face charges.

There's a clear focus to hold people accountable, said Jeffrey A. Lehtman, a Richards Kibbe & Orbe attorney in Washington who has conducted internal investigations about potential FCPA violations for business clients. Critics of the FCPA have noted the focus on extracting large penalties from corporations though corportations can only act through people.

The 'Cornerstone' of FCPA Actions

Assistant Attorney General Lanny A. Breuer in a February 2010 speech to the American Bar Association called the aggressive prosecution of individuals a cornerstone of the Justice Department's FCPA enforcement.

Those indicted can face stiff prison sentences.

In October, a former president of Terra Telecommunications in Florida received a record 15-year prison sentence after a jury convicted him for his role in a scheme to pay more than $890,000 in bribe money to Haitan officials at the state-run telecommunications company.

Few of these cases ever go to trial; company's can avoid stiff penalties, bad headlines and protracted litigation. But sometimes they do, posing a risk for a zealous Justice Department, which had just received two blows this December.

The department's first trial conviction in a FCPA case against a corporation called Lindsey Manufacturing of California was recently overturned due to prosecutorial misconduct.

In another case stemming from a Las Vegas sting operation, a judge declared a mistrial when a deadlocked jury failed to reach a verdict on charges that employees of companies in the military products industry conspired to bribe a defense minister of Gabon, a country in West African.

New Era of Enforcement

Enforcement of the FCPA has been anemic for most of the law's life. From 2005 to 2009, the Justice Department brought in four times the number of cases than in the previous five-year period. And with nearly 50 cases launched, 2010 saw more than twice as many enforcement actions from the Justice Department than in 2009.

The penalties are growing, too. As of April, criminal fines for 2010 and 2009 included eight of the 10 largest settlements in the history of the anti-corruption law, according to a December report from the New York City Bar Association.

These settlements have included the some of the most well-known corporations, like New Jersey-based Johnson & Johnson, which settled allegations of bribing public doctors in Europe for more than $70 million.

The Dodd-Frank financial reform law also created incentives for whistleblowers to report potential violations. Qualified whistleblowers can get a 10- to 30-percent cut of money collected from FCPA-related settlements, some of which total millions of dollars.

Corporate groups have has noticed the newly-robust enforcement of the anti-corruption law, leading the Chamber of Commerce to hire President George W. Bush's attorney general, Michael Mukasey, to lobby Congress on possible legislation that would narrow the scope of the 1977 law.

Ex-Bush AG Details 'Shortcomings' of FCPA

Business groups have long complained of the FCPA's vagueries and wide scope that give regulators too much power in enforcement matters. Corporations say they are at a competitive disadvantage with foreign rivals who face no recourse for making kick backs.

Executives and investment bankers have reported that the law has forced them to renegotiate or kill a deal over the last three years.

Despite the complaints, there is little they can do to fight the charges. The easiest course can be a deferred prosecution agreement, a deal that allows a company to pay a fine and avoid trial by promising to clean up its act.

Without trials, though, there is little case law for attorneys or companies to study.

As a result... the enforcement agencies have broad power and discretion to enforce the FCPA as they determine appropriate, the New York City Bar Association report said.

Mukasey, testifying on behalf of the Chamber of Commerce's Institute for Legal Reform, stressed during a June House Judiciary Committee hearing the need for the law's scope to be narrowed.

For instance, Mukasey said the definition of foreign official is too broad, covering employees of state-controlled companies considered instrumentalities of government.

The DOJ and the SEC considers everyone who works for an instrumentality, from the most senior executive to the most junior mailroom clerk, to be a foreign official, Mukasey told lawmakers, adding that the law should define foreign official as anyone working at a company in which the government holds majority stake.

He also wants the law to allow companies to avoid liability for foreign bribery if a rogue employee circumvent internal controls. Another proposed change would make it harder to land a criminal conviction against a corporation by requiring prosecutors to prove that the company intentially bribed a foreign official.

An Update to a 1977 Corruption Law?

Talk of altering the law will likely increase this year. The Senate and House have now held hearings on the matter and key lawmakers have said they will introduce legislation to alter the 34-year-old law.

The Justice Department is pushing back at the effort.

We have no intention whatsoever of supporting reforms whose aim is to weaken the FCPA and make it a less effective tool for fighting foreign bribery, Breuer, the assistant attorney general in the criminal division, said in a November speech, adding that the Obama administration next year will release detailed new guidance for companies.

The guidance should be a boon for companies complaining about operating in untested waters.

Lehtman, the Richards Kibbe & Orbe attorney, told the International Business Times that companies should put in place clear, comprehensive guidelines and training, instead of pinning hopes on a legislative fix. He noted the consternation among smaller companies about compliance costs.

While that may be a valid complaint, he said, it's not going to sit well with the regulators.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.