Artificial Human Ear Grown Using Animal Tissue, Study Is Big ‘Step Forward’ For Engineered Organs [PHOTOS]

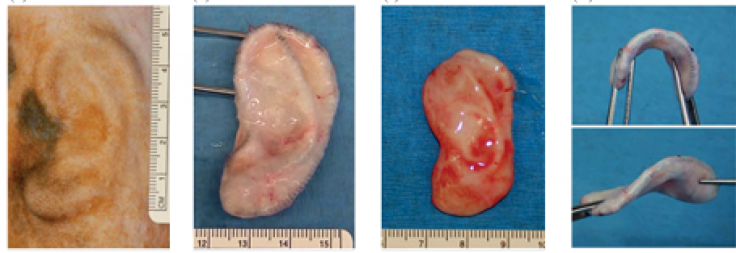

Scientists have created an artificial human ear using animal tissue from cows and sheep.

The lifelike ear is the latest development in creating substitute organs for patients who have lost or injured body parts, the BBC reports. The artificial ear, which has the same flexibility as a human one, was created using a wire frame that took the 3D shape of a real human ear.

"This research is a significant step forward in preparing the tissue-engineered ear for human clinical trials," Dr. Thomas Cervantes, who led the study, told the BBC.

In the study, published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, the new ear not only had the same “natural elastic bending” real ears have, but it also kept its shape, showing “minimal shrinkage” compared to other ears not grown on a framework, according to the study.

Cervantes reasserted these points in a BBC interview.

"One, we were able to keep the shape of the ear, after 12 weeks of growth in the rat. And then secondly, we were also able to keep the natural flexibility of the cartilage," he said, pointing to significant progress made in the study.

Once full-grown, the artificial ear was implanted into rat and mice that purposely had compromised immune systems. This allowed the ears to connect with their blood supply, preventing the transplant from being rejected, the Belfast Telegraph reports.

While the ear was smaller than a human one, it was modeled on the scale of a real ear taken from CT scans. In humans, the technique used in the study would have to be altered.

"In a clinical model, what we would do is harvest a small sample of cartilage that the patient has and then expand that so we could go ahead and do the same process," Cervantes said, pointing to how stem cells would be used in a clinical trial.

This isn’t the first time scientists have created a human ear. In July, Indiana University scientists transformed mouse embryonic stem cells into structures for the inner ear used to detect sound, head movements and gravity.

"We were surprised to see that, once stem cells are guided to become inner-ear precursors and placed in 3D culture, these cells behave as if they knew not only how to become different cell types in the inner ear, but also how to self-organize into a pattern remarkably similar to the native inner ear," Dr. Eri Hashino, an author of the study, said in a statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.