Assisted Suicide Laws 2015: Advocates See Maryland As Next Battleground, After California Passes Right-To-Die Law

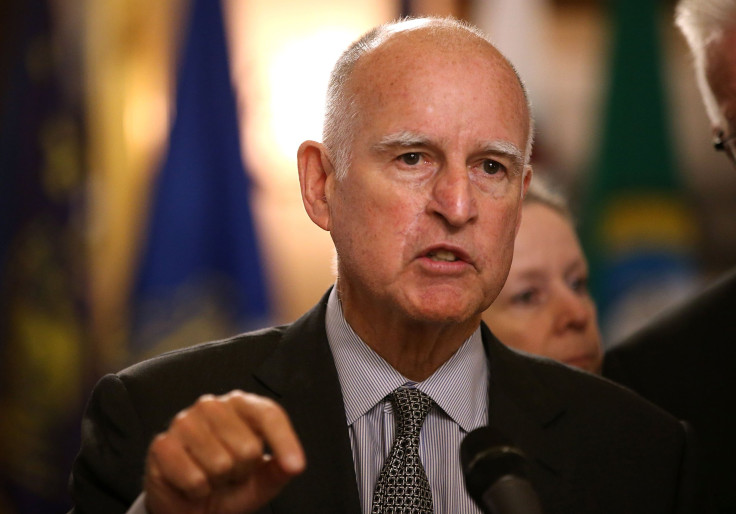

It was a yearslong, contentious debate that split doctors and patients, academics and politicians alike, but in the end, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law Monday allowing terminally ill patients to end their own lives. Now, inspired by California's success, advocates of assisted suicide in Maryland want to achieve the same victory in 2016, after an initiative this year failed in Annapolis.

The question of whether terminally ill patients should be allowed to decide if and when they should take their own lives has spilled over state borders and become a national debate, even though just five states -- Washington, Vermont, Oregon, Montana and California -- have legalized the practice. In 2014, 105 people in Oregon ended their own lives under the law.

One of them, 29-year-old Brittany Maynard, who had been diagnosed with brain cancer, moved to Oregon from California in order to do so. In her final months, she became somewhat of national symbol for the legal right to assisted suicide, speaking openly and publicly about her experiences.

Brittany Maynard's family looks back after year-long fight to pass 'death-with-dignity' bill: http://t.co/zAcFMwC7OG pic.twitter.com/16KdNVG6UZ

— ABC News (@ABC) October 7, 2015California's passage of the law “has made us even more motivated to make sure Marylanders have the same options,” Donna Smith, a Maryland-based consultant for Compassion & Choices, a Denver-based organization that advocates for assisted suicide, told the Washington Post. The organization's advocacy teams in Maryland have grown from one last year to six this year, she said.

“I think that this is a national wave,” Maryland Delegate Shane E. Pendergrass, who has sponsored right-to-die legislation, said. “The more discussion there is, the more we think about it, and the more chance there is for more lawmakers to realize that it is good to give people an option to be able to control the last six months of their life.”

The debate in Maryland over whether this right should be made legal has stretched for years. In March, a right-to-die bill in the General Assembly was withdrawn before it came to a vote. It faces staunch opposition, particularly from religious groups like the Maryland Catholic Conference, CBS Baltimore has reported.

California faced similar obstacles in passing the law, but advocates there prevailed. The governor himself is a Catholic who once studied to become a priest.

“In the end, I was left to reflect on what I would want in the face of my own death,” Brown wrote a signing message to the state Assembly. “I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain. I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill. And I wouldn’t deny that right to others.”

Compassion & Choices has said it hopes California's success in passing the law will spur other states to do the same. “This is the biggest victory for the death-with-dignity movement since Oregon passed the nation’s first law two decades ago,” Barbara Coombs Lee, the group’s president, told the Los Angeles Times after Brown signed the law.

National advocates of the right to assisted suicide are also pushing for its legalization in New York and Washington, D.C.

Check out where California and other states stand on Physician-Assisted Suicide with this map @KQEDLowdown @KQED http://t.co/pYk8qKxkWA

— KQED Edspace (@KQEDedspace) October 7, 2015© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.