Black History Month: Do Africans, Caribbean-Americans Feel Left Out Of Annual Observance?

Many aspects of Kwesi Amissah’s life reflect his blended heritage – he’s the son of a Trinidadian immigrant father and an African-American mother. Since last September, Amissah, 29, has worked at Nicholas, a New York City Afro-Caribbean and Pan-African novelty shop that sells shea and cocoa butters, fragranced body oils, incense and T-shirts bearing the faces of black historical and cultural figures like Bob Marley, Nat Turner and Nelson Mandela.

During Black History Month, when people across the U.S. are encouraged to honor the African-American experience, Amissah has struggled to find a diverse representation of black America beyond the doors of the Brooklyn storefront where he’s employed. He said he’d love to see Stokely Carmichael, the Trinidadian-American revolutionary who led the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Black Panther Party, receive as much shine in February as Rosa Parks and Frederick Douglass.

“I want to know my history, fully and comprehensively,” Amissah said in interview this week. He echoes a sentiment widely felt within the black community – that Black History Month is losing its relevance in an increasingly diverse America. “If you’re only telling 5 percent of who we are, that’s not enough to tell the whole story,” he said. “What’s the other 95 percent that we don’t know?”

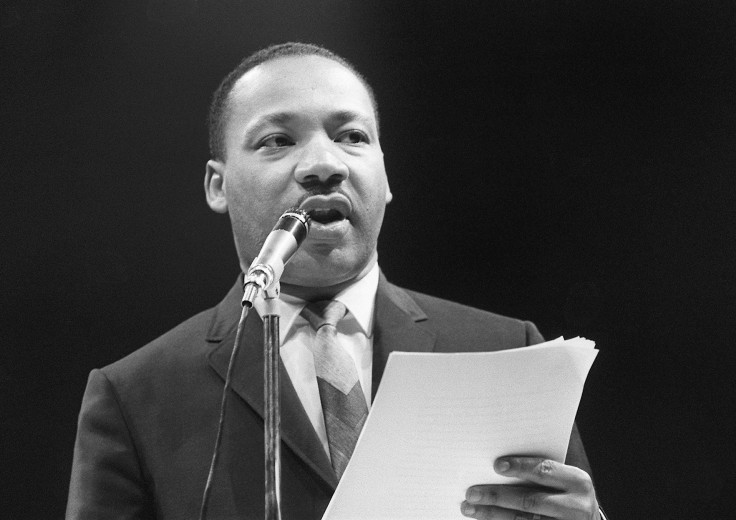

Even as some Caribbean-Americans revere black American figures like the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, there is an apparent exclusion of Caribbean-Americans in Black History Month. The largest foreign-born black population in the U.S., West Indians have even advocated for a separate National Caribbean-American Heritage Month, which is observed in June, not February. That raises the question: Is Black History Month too American-centric for immigrants of African descent and their families?

“For Haitians and Haitian-Americans, Black History Month is different because we received our independence in 1804,” said Samuel Pierre, a 31-year-old Brooklyn-born entrepreneur whose mother emigrated to the U.S. from Haiti in 1980. “If you asked my mother right now, she’d say they didn’t have a civil rights movement like the U.S. She doesn’t know what it means to need a Black History Month.”

But Pierre’s mother does understand the value of hard work. With just an eighth-grade education, she worked as a janitor to provide for Samuel and his siblings, Pierre said. As the executive director of the Haitian American Caucus, a tech-themed coalition catering to the community, his own work ethic is a shared pan-Caribbean value that hasn’t been snuffed out by American racism and discrimination, he added.

Figures like Philippe Wilson Desir, the former Haitian consul general in New York known for his fierce advocacy in the 1980s and 1990s, would be someone to celebrate in February, Pierre said. Desir, who died in 1995, exemplified the spirit of Caribbean people who were trying to build new lives in the U.S. and maintain a connection to their homeland.

New York and Florida are the major hubs for the Caribbean-American community, which was estimated at 4 million people nationwide in 2014, according to the U.S. Census Bureau's most recent statistics. Over the last five years, immigrants from countries including Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and Haiti have increased their populations in the U.S. The African immigrant population, by comparison, was estimated at 1.9 million people in 2014.

Many Caribbean-Americans come to the U.S. from a diverse array of cultures and political climates in majority-black nations looking for economic opportunity — and they tend to find it. The median household income for Caribbean-Americans was estimated at $41,155 in 2014. The population had an overall unemployment rate of 5.9 percent that year, slightly higher than the overall national rate.

Conversely, African-Americans — African descendants who have lived in the country for centuries — were about 13 percent of 310 million U.S. residents in 2014, according to census data. The median household income was $35,600 in 2014. The unemployment rate was 10.4 percent that year, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. African-Americans, however, emerged from the chains of slavery, only to face Jim Crow segregation, employment discrimination and other institutional forms of racism that relegated many to a lower socioeconomic class, when compared to whites. Their plight inspired the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, when King and Parks, among others, emerged as key figures.

Even some African-Americans have grown bored of how Black History Month is celebrated in the U.S. because King and Parks repeatedly receive the most exposure. Historian Carter G. Woodson is credited with starting the Negro History Week campaign in 1926 that would eventually evolve to Black History Month as a national observance. At the time, foreign-born blacks were less than 3 percent of the U.S. population, according to Christina Greer, associate professor of political science at Fordham University in New York City, whose book, “Black Ethnics: Race, Immigration and the Pursuit of the American Dream,” was published in 2013.

“I was kind of tired of the same tropes” about Black History Month, Greer said in a phone interview this week. “I just realized that there are so many other people that could and should be celebrated.”

Several Caribbean-Americans reached for this article agree with Greer, at least on the point of their inclusion in Black History Month celebrations. But there is also a sentiment among Caribbean-Americans that Black History Month has become a crutch for those who want to wallow in oppression and not work harder to overcome.

“For certain people, there’s the ‘why can’t we just work hard’ line, a common immigrant narrative across the board,” Greer said. “But then there are people who realized that there are certain institutions that don’t care whether you’re black, Caribbean or African. You can play by the rules and still end up on the other side of a bullet.”

The Black Lives Matter social justice movement in the U.S. has called out police killings of African-Americans. But police violence has also been protested by black immigrants, who have been the victims of notorious profile brutality as well. In 1997, Haitian immigrant Abner Louima was beaten and sodomized with a broomstick at the hands of New York City police, after officers incorrectly believed he assaulted one of them outside of a nightclub. Louima’s case sparked national outrage in the black community, as did the 1999 police shooting death of Guinean immigrant Amadou Diallo. He was shot 41 times by New York police officers who believed he was armed, although he was not and had only been reaching for his wallet.

When Black History Month rolls around, the exclusion of the black immigrant experience is felt. Even President Barack Obama, the first black U.S. president and son of an African father, tailored this year’s “African- American History Month” message to familiar themes in the black history curriculum. “For too long, our most basic liberties had been denied to African-Americans, and today, we pay tribute to countless good-hearted citizens — along the Underground Railroad, aboard a bus in Alabama, and all across our country — who stood up and sat in to help right the wrongs of our past and extend the promise of America to all our people,” Obama stated in a written proclamation released by the White House.

Samuel Roberts and his wife, Guenet Gittens-Roberts, are Guyanese immigrants in central Florida who said they grew weary of how Black History Month has remained American-centric and often fails to look for history predating the trans-Atlantic slave trade. “There were kings and queens and royalty in our blood lines,” said Gittens-Roberts, who with her husband publishes the Caribbean American Passport Magazine.

“Coming from Guyana, I truly believe the only thing stopping you is you,” Samuel Roberts said. “The harder you work, the richer you get. But because race is so important in the U.S., there is this social feeling among African-Americans that you can’t get beyond your situation because you are black. This is an advantage that Caribbean people have. There is a social feeling that we can always overcome.”

To reflect those values, the Institute for Caribbean Studies, a Washington-based advocacy organization, led a movement to create National Caribbean-American Heritage Month. After the House of Representative passed a bill sponsored by Rep. Barbara Lee, D-Calif., the first heritage month was celebrated in 2006. However, it is not meant as a replacement for Black History Month, a common misperception expressed when it was first proposed, said Claire Nelson, president of the institute.

"It was never about creating a cultural extravaganza [like Black History Month] but about creating a political organizing space for Caribbean-Americans,” Nelson, who is of Jamaican heritage, said in an interview this week. “It’s an opportunity to get people to see themselves as ‘other’ and have some links back to the region.”

Beyond national observances, the country’s black populations need to be looking toward their common future, Nelson said. “It’s time to begin the conversation about the future of black America. What will it look like in 2030 or 2100?”

She added: “We’re still living on the “I Have A Dream” speech.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.