Border Crisis: What Happens To Child Migrants After They Are Deported?

Thousands of Central American child migrants have entered the United States in recent months, but thousands are also being deported back even before they reach the U.S. border. Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala are bracing for more deportees in the coming months, and with government resources already stretched, the fate of deported child migrants is still largely unknown.

Deportees returning to Central America are screened by government migration officials at entry checkpoints and then reunited with family members who transport them home. But government care generally ends there, and none of the three “northern triangle” countries -- which have among the highest homicide rates in the world -- has a formalized system to ensure that deportees are safely reintegrated into their communities.

“In terms of what actually happens to the kids and what conditions they go back to, there is no real follow-up,” said Richard Jones, deputy director for the Catholic Relief Services’ Latin America program, who is based in El Salvador.

Jones recalled speaking with a Salvadoran woman who was recently deported along with her children after gang members threatened her two daughters. “She was picked up in Mexico and sent back by bus, and said, ‘Now where do I go? There will be repercussions, and if I move somewhere else that I can afford, they’re going to find out.’”

There are few options for deportees -- particularly children -- returning to similar situations, and Jones said that government funds are generally too limited to provide protection and reintegration services. “The government [in El Salvador] is designing a fairly robust repatriation program that they would like to have in place, but they don’t have the resources to do it right now,” he said. “They know that it would be great to have trauma therapy and counseling immediately, because a lot of kids are very vulnerable and have suffered abuses along the way. Those services don’t exist right now.”

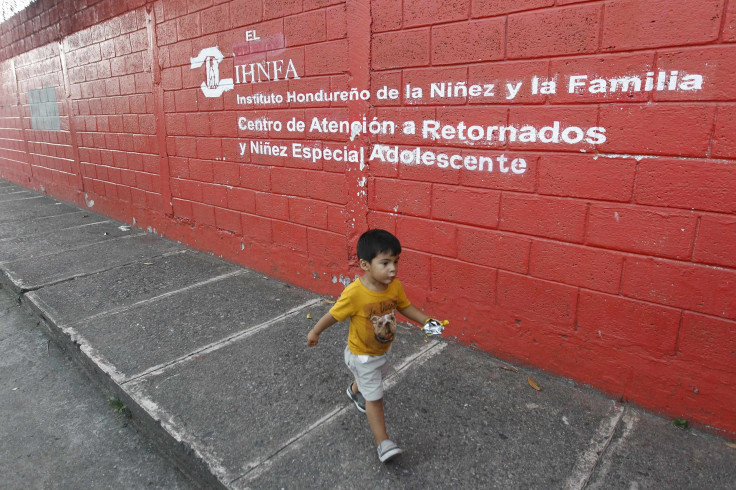

In Honduras, the source of roughly half of the unaccompanied child migrants who entered the U.S. in the past year, the national child protection agency was dissolved earlier this year after an investigation found alleged dysfunction and abuse in the department. The government created a new agency in June as a replacement, but it still faces the same resource shortages that prevent it from being able to track the welfare of deported children.

In some areas, NGOs have attempted to fill the void with counseling, job training and other services for young deportees. Kids in Need of Defense (KIND), a U.S.-based organization that primarily provides legal services for unaccompanied child migrants, runs a pilot program in Guatemala focused on reintegrating child deportees.

Megan McKenna, communications and advocacy director for KIND, said the project has largely been successful so far. “The large majority [of participants] haven’t tried to re-migrate,” she said. But the program’s reach is still too limited to address the thousands of children who have been deported there over the past year.

Despite reintegration efforts, ongoing violence and endemic poverty push deportees to try their luck at migrating again. Moreover, many smugglers who are paid to take migrants on the journey to the U.S. border -- known as coyotes -- allow for repeat attempts if migrants are deported. “The way it works is that you get three tries for your money,” Jones said.

Human rights organizations have called on the Obama administration and Mexican and Central American governments to band together to create a regional approach to the migration influx, rather than relying on deportations to stem the flow. “This situation will keep happening unless we address the root causes,” McKenna said. “The ways the U.S. can do that in part is through development assistance, in particular, and helping the countries bolster their child welfare systems.”

The White House’s proposed $3.7 billion in funds to manage the influx at the border includes $300 million to the State Department to assist Central American countries’ repatriation efforts. But so far the request has no specifics for what institutions or services the money would fund. Obama is set to meet with the presidents of Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala in Washington on Friday to further discuss regional approaches to the border situation.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.