California sperm donor at odds with federal regulators

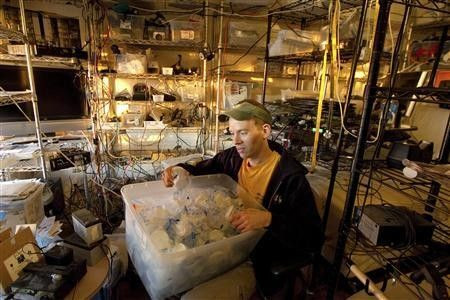

An electronics company engineer who the U.S. government considers a one-man sperm bank has fathered an estimated 14 children through free donations of his semen that he advertises over the Internet.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration says the San Francisco Bay-area sperm donor poses a threat to public health and has ordered him to stop or face up to a year in prison and a $100,000 fine.

But Trent Arsenault, a healthy, 36-year-old bachelor who professes a strong religious upbringing, sees his sperm giveaways as acts of compassion and insists he's not abandoning his genetic generosity without a fight.

Whatever happens with me sets a precedent, which could mean a lot of childless couples, he told Reuters on Monday. Does the government need to be in people's bedrooms?

He and the FDA are now embroiled in what is believed to be the first legal battle of its kind, one that has drawn national media attention and could test the limits of the agency's authority to regulate private donations of sperm offered as gifts directly to prospective mothers rather than through commercial sperm banks.

Such donations, often provided by men who are close friends of the recipients, have grown more frequent as single women, lesbian partners and heterosexual couples with fertility problems increasingly turn to alternative sources for artificial insemination.

Arsenault's prolific willingness to share his genetic material, which he promotes on a website touting his fitness as a donor, caught the scrutiny of the FDA.

PROLIFIC DONOR

During the past five years, he has given his sperm on more than 328 occasions to at least 46 women, resulting in 14 births, according to the FDA's best estimates from documentation Arsenault himself provided. This, the agency maintains, poses a risk to public health.

Under FDA's regulations, sperm donors are required to be screened for risk factors that may increase the chances of transmitting a communicable disease, FDA spokesperson Rita Chappelle explained in an email.

Sperm banks must comply with precise requirements that include a battery of tests to ensure that the donated sperm does not carry human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B or C, syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, human T-lymphotropic virus, cytomegalovirus or various genetic disorders.

Arsenault gets himself screened every six months for that entire list of diseases but cannot afford the specific FDA-approved tests he is supposed to undergo within seven days of each sperm donation, at a cost of $1,700, he said.

The stringent, costly testing regimen is the main reason sperm banks charge hundreds of dollars for their services, says Sherron Mills, executive director of the Pacific Reproductive Services in San Francisco.

Rates there range from $425 to $600 or more per insemination, and any woman who finds such a sum too onerous to pay is probably unable to afford routine costs associated with being a parent, Mills said. Once you have kids, it costs every bit as much every month, she said.

INSPECTORS AT THE DOOR

FDA regulators paid four visits last year to Arsenault's home in Fremont, California, a few miles east of San Francisco, to inspect what they regarded as his sperm-bank operation there, even though he only provides his own semen and does not charge for his services.

The FDA's inquiry culminated last fall with one final visit by agency officials to his home, accompanied by police, to hand-deliver the cease-and-desist order.

Chappelle declined to say whether the agency is investigating any other freelance sperm donors, many of whom advertise their services on the Internet. But Arsenault has retained a lawyer who is handling his court challenge.

Pending the outcome of the case, the FDA has refrained from enforcing its order, and Arsenault said he has continued to donate sperm.

Besides providing greater health safeguards, Mills said, sperm banks offer their customers stronger legal protection from donors who might try to assert their paternity rights after a child is born.

Arsenault signs forms waiving any parental rights. But Mills said such agreements have been voided in some California cases when a medical doctor was absent from the transaction.

Eleanor Nicoll, spokeswoman for the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, said the involvement of a physician is beneficial in and of itself. If you're trying to address a medical problem, you should seek medical treatment, she said.

But Arsenault argues that outlawing the kind of free service he provides runs the risk of driving some women to seek sperm donations from more questionable sources.

If you shut out the sperm donors, they are going to have to meet some bar dude, he said. Spouses would have to cheat on each other.

Arsenault said he gets to know couples before donating to them and maintains relationships with many of the children conceived with his sperm, one reason he doesn't want to stop.

I have made a commitment to families I donated to, he said. It's a big emotional process to partner with a donor.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters {{Year}}. All rights reserved.