China Bans References To Tiananmen Anniversary, As Social Media Firms Promise A 'Friendly' Internet

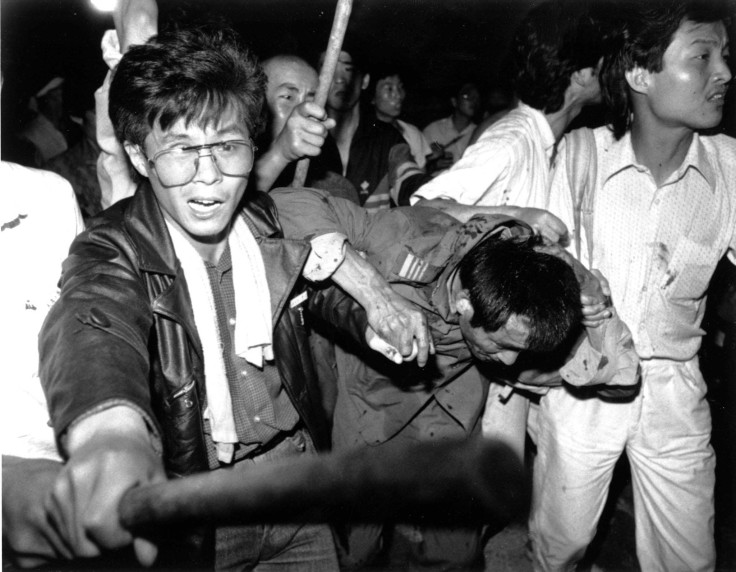

SHANGHAI -- China marked the 26th anniversary of the crackdown on the Tiananmen Square protest movement with its traditional response: official silence and an attempt to delete all references not only to the event but also to the date it happened, June 4. Chinese Internet users have long grown used to posts mentioning the date -- written 6.4 in Chinese -- being deleted; even the popular alternative, May 35, is itself now banned.

But this year some observers expressed surprise that, on Wednesday, it even appeared to be impossible to transfer amounts of money involving the figure 64 via the payment service on popular social media app WeChat -- though the Wall Street Journal said these appeared to be working again on Thursday. Even a post by the official People’s Daily newspaper including the number 64 was recently deleted from Sina Weibo, China’s biggest microblogging site, according to monitoring organization Free Weibo. And one Hong Kong-based journalist noted on Twitter that even the phrase “26 years” appears to be unacceptable this year.

It’s no great surprise, though, in a nation which, according to a foreign ministry spokeswoman this week, “already reached a clear conclusion” on the events of 1989 -- which are still officially described as a “counter-revolutionary rebellion” -- many years ago. As one young author recently noted, official history textbooks skate over or simply ignore the events of 1989, which brought millions of people onto the streets of cities across China, in calls for an end to corruption, and for political reform.

But with the Chinese authorities currently engaged in a campaign to stamp out foreign liberal ideas, in what Amnesty International this week described as “one of the darkest periods for freedom of expression in China since the bloodshed of 1989,” one of China’s more hawkish media outlets has gone on the offensive in recent weeks.

The official Global Times newspaper, a tabloid offshoot of the Communist Party’s traditional mouthpiece, the People’s Daily, has published two commentaries insisting that even those who took part in the protests as students in 1989 have now “reached a consensus” that they were naïve and mistaken, and implying that the country’s dramatic economic growth over the past two decades proves that the Communist Party was correct in valuing stability over the lives of protesters.

The most recent article, published last week, was written in response to a letter apparently written by Chinese students in the U.S., which called for a reassessment of the events of 1989. Such young people, the commentary said, must have been “brainwashed,” and were “twisting the facts of 26 years ago with narratives of some overseas hostile forces,” in order to “tear apart society.” In fact, it said, Chinese society was moving forward, and had therefore “reached a consensus on not debating the 1989 incident.”

In an earlier article, the Global Times similarly denounced students in Hong Kong who had protested against a visit to their university by members of China’s People’s Liberation Army, because of its links to the Tiananmen crackdown. It said these young people were naïve and out of touch, and added that they should be “grateful that they live in such a tolerant era.”

Yet the fact that the Global Times saw it as necessary to write these commentaries may also reflect continuing official anxiety about how effective the party’s campaigns of patriotic education, launched in response to the 1989 protests, have been in winning over China’s young generation. One of the authors of the letter, which so annoyed the Global Times, said in an interview with the Associated Press that he wanted to make sure that the young generation did not “forget, nor forgive.” And one young woman in Beijing also wrote recently of how she came to a different conclusion from that of the government -- and even other members of her own family -- about the events of 1989.

Such comments are likely to add to the Chinese authorities’ determination to step up controls on China’s Internet -- which the nation’s army newspaper recently described as being a “battleground” where hostile forces were seeking to poison the minds of the young generation against the Communist Party.

In the latest in a series of moves, China’s police ministry this week announced that the country’s shadowy cyber police would be opening their own public accounts on social media, and encouraged ordinary citizens to denounce unhealthy content.

And on Tuesday, the recently established Internet watchdog the Cyberspace Administration of China, announced a separate campaign to clean up the use of “vulgar language” and catchphrases online, saying that these would “influence adolescents’ values.” The campaign targets the often irreverent catchphrases, some of which mock official propaganda slogans, that have become popular online over the past decade, during which the Internet has offered young Chinese people a new platform for free expression and, sometimes, criticism of the authorities.

Currently however, the authorities appear determined to rein in the relative freedom the Internet has brought this generation, particularly where it involves alternative views of China’s political system -- and of its politically loaded history.

And China’s big Internet companies this week expressed their willingness to support the authorities’ latest campaign: an official from Sina Weibo, quoted in the Global Times, said that the company would launch a campaign to “promote a friendlier cyberspace environment,” and would issue warnings to “spiteful netizens,” while an official from Tencent’s qq.com site said the firm would “prominently place friendly posts,” and “guide netizens in the proper use of language.”

One place where such guidance has yet to take full effect is Hong Kong, where the annual demonstration in memory of the Tiananmen crackdown took place in the city’s Victoria Park on Thursday evening. However, last year’s protests against China’s planned electoral system for Hong Kong’s next chief executive have led some young people to say they will not take part this year, as they do not want to be involved in events linked to the mainland at all. Meanwhile several of Hong Kong’s main pro-China newspapers marked the day by carrying front pages featuring the identical slogan: “Hong Kong needs stability, Hong Kong needs development.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.