China's Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFV): 7 Things You Should Know About China's Local Debt Bomb

Among all the things that keep Chinese leaders up at night – pollution, food contamination scandals, income inequality and even the danger of Western constitutional democracy – there is one that, if left unaddressed, could have a ripple effect well beyond China's borders. The country is sitting on a municipal debt time bomb, and the clock is ticking.

Premier Li Keqiang said on Sept. 11 that China is taking “targeted measures” to address the issue of local-government debt that “people are all concerned about.”

Here are seven things you should know about China’s local government financing vehicles, or LGFVs.

1. So what are LGFVs?

Local government financing vehicles, or LGFVs, are entities set up by local governments to raise funds primarily for costly infrastructure and real estate development projects. Simply put, LGFVs are state-owned companies that raise funds for local governments. And these companies have long been flagged as key source of risk to the banking system.

2. Why do LGFVs exist anyway?

Since the late 1990s, local governments have been creating financing vehicles backed by land revenues and public assets to borrow money from banks or institutions investors for funding projects, according to the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

In contrast to state governments in the U.S., most local governments in China are forbidden to borrow money directly.

Historically, land sales have been a large revenue source for local governments, but since the global financial crisis this revenue source has diminished. Yet local government spending, especially on infrastructure investments, has accelerated.

Setting up LGFVs was seen as the solution to this local government financing problem. While owned by the local government, these financing vehicles can raise funds through the more traditional methods of taking bank loans, issuing bonds, and via equity market initial public offerings, as well as via shadow banking activities such as trust loans.

3. What went wrong?

The model came under criticism following the global financial crisis in 2008. Many local governments undertook major spending projects – building new railways, subways and airports -- to keep economic growth on track, and much of this was financed through special investment companies.

Beijing is concerned that many LGFV loans obtained in 2008-09 were poorly collateralized and project cash flow estimates were overstated. These local infrastructure projects, some of which are potentially loss-making, often take years to generate investment returns, raising the risk of default.

After stabilizing in 2011, local debt surged again last year as policymakers launched a new wave of infrastructure spending to stabilize the world's second-largest economy amid its slowest growth in 13 years. Official data now show LGFVs account for 14.7 percent of outstanding bank loans.

“Dangerously, LGFVs are relying increasingly on new debt to finance long-term investments,” Nomura economists led by Zhiwei Zhang wrote in a note to clients.

4. How serious is the problem?

Regional governments set up more than 10,000 LGFVs after they were barred from directly issuing bonds under a 1994 budget law. These financing vehicles’ debt grew 39 percent from 2010 to 19 trillion yuan ($3.1 trillion) as of the end of 2012, according to Nomura’s estimate. That’s 37 percent of gross domestic product.

Nomura’s number roughly matches a recent estimate by Yuhui Liu, an economist in the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a government research organization in Beijing.

Fitch puts China's overall sovereign debt at 74 percent of GDP by the end of 2012, of which 49 percent is central government and 25 percent is local.

Standard & Poor’s estimates banks’ LGFV exposure at around 14 trillion to 15 trillion yuan by 2012. The official non-performing loan ratio in the banking system stood at 1 percent in 2012, but many investors are skeptical about this number because it does not reflect the potential risks from local government financing vehicles and other vulnerable sectors.

5. Should we be concerned?

The short answer is: yes.

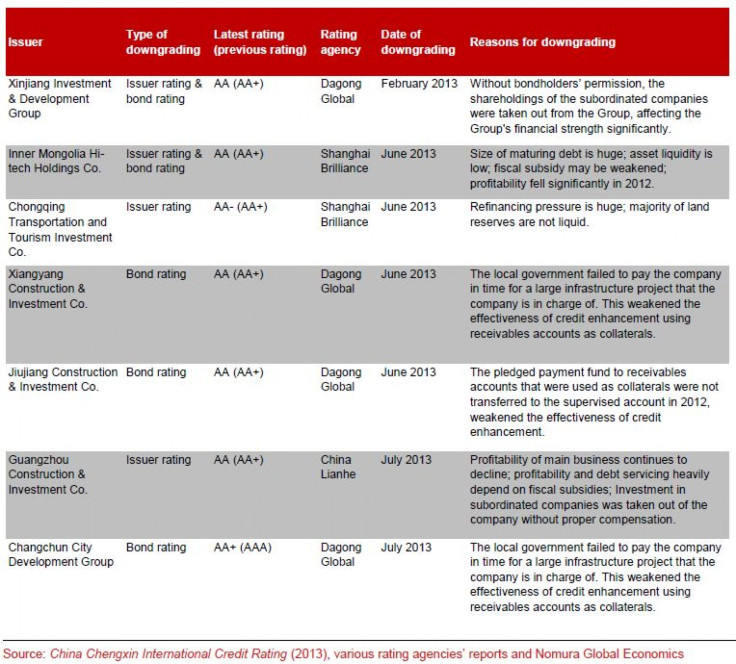

Rising concerns in the market over LGFV debt are illustrated by the growing number of domestic rating agency downgrades of LGFV credit ratings. According to Nomura, so far this year there have been seven ratings downgrades by different agencies, whereas this was a very rare occurrence before, suggesting that financial conditions have deteriorated rapidly and investors are increasingly worried. These downgrades will lead to higher financing costs, making it more difficult for LGFVs to sustain their debt.

In April, Ke Zhang, the head of a major auditing firm in China and the deputy head of the China Auditors Association, said in an interview that the local government debt problem is “out of control” and “could spark a bigger financial crisis than the U.S. housing market crash.” Two months later, the rating agency Moody’s pointed out that local government debt is a key risk facing China.

On July 28, the central government urgently requested the National Audit Office stop other work to specifically carry out a national audit on local government debt. China watchers expect the results to be published in the coming weeks, probably before a plenary session of the Communist Party Central Committee in November, at which more details of China’s broad economic overhaul are likely to be communicated.

Nomura estimates that without local government support to LGFVs, over half of LGFV debt would have been at risk of default in 2012. In the case of a liquidity crisis, that number could easily go up to 70 percent.

“We believe a number of LGFV defaults may be allowed in 2014 to address a major moral hazard problem,” Nomura’s Zhang said.

5. The likelihood of a Detroit-style default?

While Detroit versus Chinese local government isn’t exactly apples to apples, it’s still interesting to put them side by side.

Detroit filed for bankruptcy with debts of $18 billion on July 18, but this is the average amount of debt for many Chinese cities. A 2012 audit of 36 local governments found $624.6 billion in debt -- suggesting there are at least a few Chinese cities with debt equal to, or in excess of, the $18 billion that sunk Detroit.

You get the picture.

6. What could trigger an actual crisis?

Nomura’s economists laid out several possibilities. A repeat and prolonged liquidity squeeze like that seen in June is one scenario. Another could be a re-pricing of credit risks in LGFV debt once credit defaults begin. In this case, new issuance would become difficult and liquidity risks are far more likely to materialize. A third trigger could be a decline in property prices, bringing down land sales and fiscal revenue, thus limiting fiscal subsidies to LGFVs.

7. Implications for economic growth in 2014?

The government faces a difficult choice.

There is an obvious trade-off between economic growth and dealing with the risks posed by LGFV debt levels. Economic growth has been sustained at above 7 percent for the last five years, in large measure due to expanding LGFV debt that helped finance infrastructure investment.

“We believe the government would favor slower growth with less risk,” Nomura’s Zhang said, adding that this would mean 2014 GDP growth will slow to 6.9 percent, from 7.5 percent this year.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.