Climate Change 2016: As Proxy Season Arrives, Shareholder Activists File Record Number Of Environmental Resolutions

As major U.S. companies head into their annual shareholder meetings this spring, firms are facing a record number of proposals to curb corporate carbon emissions and prepare for the threats of climate change.

While the movement of shareholder activists has been steadily building for years, the Paris climate agreement reached in December has fueled a surge in climate-focused resolutions. Shareholders — including giant state pension funds, private foundations and individuals — are pushing public companies to not only reduce their environmental impacts but also develop long-term strategies to navigate a world of tougher regulations and rising climate risks.

“We’re a multigenerational investment fund, so climate change is a very real risk and opportunity for us,” said Anne Simpson, director of global governance at the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS), the nation’s largest pension fund and a prominent shareholder activist. “We’re looking ahead in decades,” she said.

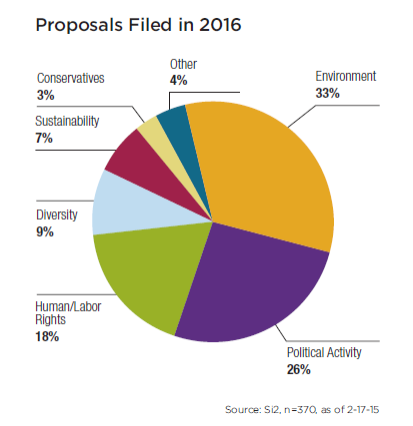

Shareholders have filed 94 proposals tied to climate change as of February, a 15 percent bump from the 82 proposals filed in 2015, according to a recent report by the groups As You Sow, Proxy Impact and Sustainable Investments Institute.

About one-fifth of this year’s resolutions raise questions about how businesses can succeed in a low-carbon economy. Nearly 200 nations in Paris agreed to limit the rise in global average temperatures to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), a target that — if enforced — would require the world to avoid burning 80 percent of its existing oil, coal and natural gas reserves.

For major energy producers like Exxon Mobil Corp. or Peabody Energy Corp., that means leaders will have to devise new business strategies or risk going belly-up. Shareholder proposals up for vote this spring will ask companies to pinpoint their vulnerabilities in the global shift toward cleaner energy and outline their survival plans if the value of fossil fuels goes up in smoke.

“There’s some real concern about if these companies are prepared and wanting to know what their strategies are going forward,” said Michael Passoff, CEO of Proxy Impact, a proxy advisory firm in California.

Shareholders are also increasingly pushing companies to power their offices and operations with renewable energy like wind and solar power. Public utilities such as Duke Energy Corp. and Entergy Corp. received nearly a dozen resolutions urging the companies to detail plans for adopting more distributed energy sources, such as rooftop solar installations or battery-powered microgrids.

A third bucket of shareholder proposals urge businesses to limit their environmental impacts, including by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and reducing harmful methane leaks from oil and gas operations. Some measures ask large energy firms to set distinct goals for measuring and reducing impacts related to hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, the technology that’s helped fuel the U.S. shale oil and gas boom.

Exxon and Chevron have the dubious distinction of facing fracking proposals for the sixth consecutive year, as the companies in years past have failed to reach an agreement with shareholders. Both energy giants tend to draw roughly 10 resolutions each year, a result not only of their size as producers but also lack of responsiveness, Passoff said.

“Shareholders see very little sign that they’re changing their ways, and that’s why they continue to be a target,” he said.

The two U.S. oil giants earlier this year asked the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to refuse shareholder votes this year on a proposal urging them to analyze the financial impact of carbon regulations on their operations. Exxon told regulators the resolution was vague and asked for metrics that are tough to quantify.

The Texas energy producer in the past has said that climate change poses little risk to its reserves since it expects demand for oil and gas to remain strong for decades. Exxon is separately fighting an inquiry by New York State’s attorney general into whether it misled the public and shareholders about the risks of climate change — a question raised by investigations from the publications InsideClimate News and the Los Angeles Times.

But the pension fund CalPERS, the New York State comptroller’s office and three other Exxon shareholders urged the SEC to force the oil producer to bring the resolution to a vote at the annual meeting in May. In March, regulators agreed with the activists, ordering Exxon and Chevron to allow a vote.

“As investors, we need to know how Exxon Mobil’s bottom line will be impacted by the global effort to reduce emissions and what the company plans to do about it,” New York Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, who oversees the state’s $178.3 billion pension fund, said in an earlier statement.

Simpson, the CalPERS director, said other major corporations have been more responsive to shareholder proposals on climate change. The pension fund, which has a $300 billion portfolio of 10,000 companies, recently co-filed a resolution to global coal mining giants Glencore Plc, Rio Tinto Plc and Anglo American Plc to report their plans for surviving under regulations to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius. All three companies have agreed to bring those proposals to a vote.

“This is a real breakthrough moment,” Simpson said. “We’re getting companies to acknowledge that this isn’t something to fight about with their owners.”

But even as more companies get on board, the shareholder activist moment still faces criticism from organizations that say the best path for pressuring companies is to divest holdings from the companies entirely. The Fossil Free divestment campaign, spearheaded by national green group 350.org, argues on its website that, “If it is wrong to wreck the climate, then it is wrong to profit from that wreckage.”

In California, legislators recently passed a bill requiring CalPERS and other state pension funds to review their investments in coal companies and consider severing ties. In late March, two California Democratic congressmen sent a letter urging CalPERS to divest from Exxon, saying it is “morally suspect” for the pension fund to invest in the oil giant.

But Simpson said she disagreed that divesting from fossil fuel companies was the best approach for addressing climate change. She argued that by remaining shareholders in large energy firms, CalPERS and other investors could collectively influence the businesses to move in a cleaner direction.

“In our experience, if you sell your shares you do not have any impact on the company. The company does not change strategy,” she said. “Exxon will continue to do what Exxon is doing. What we want from Exxon is a new approach to the [low-carbon] transition.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.