Cliven Bundy And The Second Sagebrush Rebellion: A Brief History Of The Movement To ‘Reclaim’ The American West

It was early March when the Bureau of Land Management sent a long overdue letter to Nevada cattle rancher Cliven Bundy informing him that his 900 cows would be impounded and he would have to pay $1.2 million in fees for grazing on federal land without payment since 1993. When officials held true to their threat two weeks ago, Bundy made some threats of his own, propelling the spat onto the national stage.

Over the past two weeks, the aging rancher has not only gathered a makeshift militia of several dozen armed protesters to protect his herd, he’s galvanized the conservative media around the plight of land control in western states, where the federal government is a dominant force.

The fee Bundy is accused of skipping for more than two decades now stands at $1.35 per cow, per month. The Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, collects that money to offset costs of maintaining roads, water and the health of the fields the cows graze. Bundy, however, argues that the land was never the federal government’s to take, and, thus, it has no right to manage it or charge him for its services.

Threats of repeated violence had kept the BLM from doing anything about Bundy’s “trespass cows” for decades until its bungled attempt to confiscate 400 of them on April 5. After Bundy invited dozens of supporters to travel to a dusty stretch of land about 80 miles east of the Vegas Strip and aim their rifles at federal employees, the federal government stood down. It returned the cows, and promised to resolve the matter “administratively and judicially.”

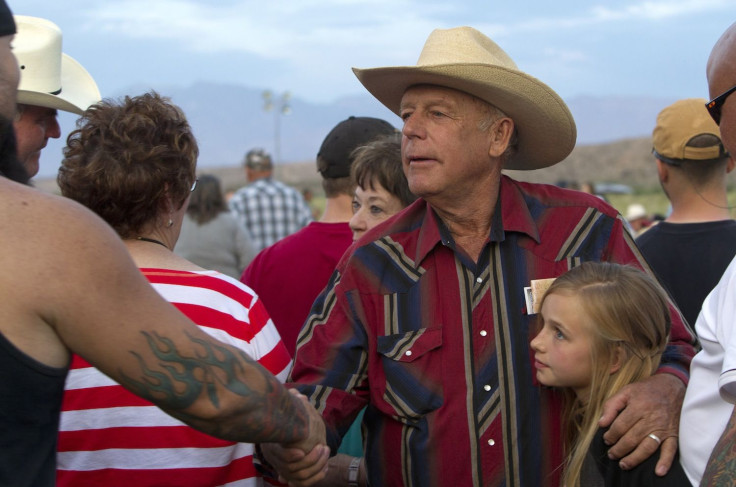

That’s were things stood as of this past weekend, when Bundy held a party at his ranch to rally support. He’s made it perfectly clear on his blog that his far-right, Libertarian standoff is about much more than a few wayward cows. The way Bundy frames the argument, the fight is about states’ rights and the feeling some in the West have that the federal government is oppressing their privilege to mine, log and farm on American soil.

This ideology recently gained some ground in Arizona with Proposition 120, the Arizona Declaration of State Sovereignty Amendment, which declared “sovereign and exclusive authority and jurisdiction over the air, water, public lands, minerals, wildlife and other natural resources within [the state’s] boundaries.”

The controversial 2012 ballot measure, backed by Republicans in the state legislature, would have essentially transferred control of parks like the Grand Canyon from the federal government to the state if it had passed, which it didn’t. In fact, voters handily rejected the proposition by a margin of 2-to-1, but it opened up a dialogue that has persisted to this day, as the case of Bundy and his militia proves all too well.

The argument that the West was “lost” to the federal government and needs to be “taken back” by the states is a recycled one that harkens back to the so-called Sagebrush Rebellion of the 1970s. One of the central tenants of that movement was that the West’s destiny is dictated by outsiders in the East who don’t have a clue about what those in the West need. Land rights activists further argue that the federal government has loved the land to death, paving the way for massive wildfires that could be prevented through managed logging and grazing.

The burning question for many is: How did all of this land west of the 100th meridian (or the “Federal Fault Line”) get gobbled up by the federal government in the first place? The answer is simple: It wasn’t very flat, wasn’t very arable and wasn’t recognized at the time for having many resources.

Federal land was never actually meant to exist in the early days of the United States. It was seen as an asset to be distributed for the growth of the economy, but by the end of the 19th century, the federal government was left with tracts of land that nobody wanted. This just so happened to coincide with the rise of the conservationists and the ascent of Teddy Roosevelt to the White House in 1901.

The idea that national land was part of our collective American heritage really took hold in the 20th century with the rise of the National Park Service. In fact, the notion of public land for all to enjoy -- foreign nearly the world over -- was called “America’s best idea,” and it remained so in most minds until the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 came along.

Essentially, the act authorized the BLM to designate places many in the West used for herding, mining or even archeological studies as national wilderness areas. The Sagebrush Rebellion was born.

The movement died off after the Reagan years, but has once again gained steam with newly formed groups like the American Lands Council, a Utah-based organization that believes the federal government has reneged on a promise to return lands to western states. And then there is Bundy, whose vision of political liberty is, perhaps, on another level altogether. “I abide by all Nevada state laws,” he said during a recent radio interview. “But I don’t recognize the United States government as even existing.”

The irony, of course, is that his “trespass cows” have trampled over as many state and local laws as they have federal, making him a lawbreaker no matter who you choose to ask.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.