Cyprus Crisis 2013: Who Is Next? Slovenia, Slovakia, Luxembourg And Malta Face Contagion From Cyprus As Banking Crisis Deepens

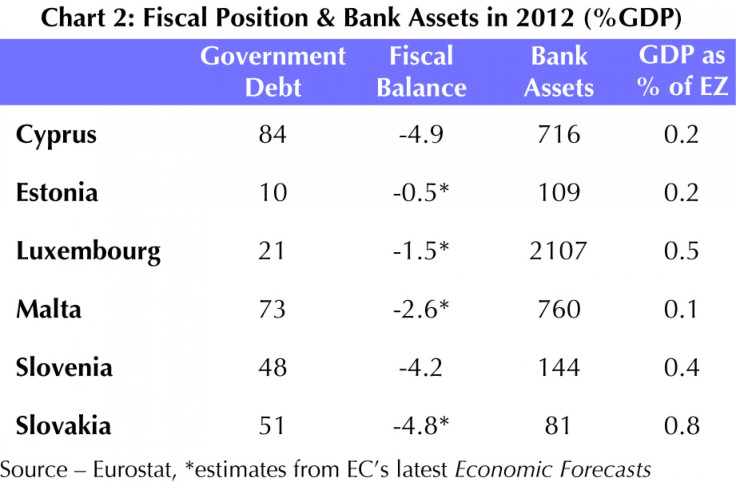

Although policymakers averted a crisis in Cyprus, the messy bailout deal has dragged other tiny economies with big banking sectors into the spotlight.

Cyprus secured a €10 billion ($12.9 billion) package of bailout loans on Monday. The deal also forced it to close its second-largest bank, inflicting significant losses -- possibly up to 40 percent -- on all deposits larger than €100,000.

In a speech in Moscow last week, European Commission President José Manuel Barroso said the crisis in Cyprus was "the result of an unsustainable financial system” that is multiple times bigger than the gross domestic product of the country. He said it’s a system that “certainly has to adapt."

A Reuters poll conducted this week showed that most economists believe Cyprus won’t be the last euro zone country to ask for an international bailout.

Slovenia

The draconian bailout conditions for Cyprus have soured investor sentiment in Slovenia, also a small euro zone member with an overburdened banking sector.

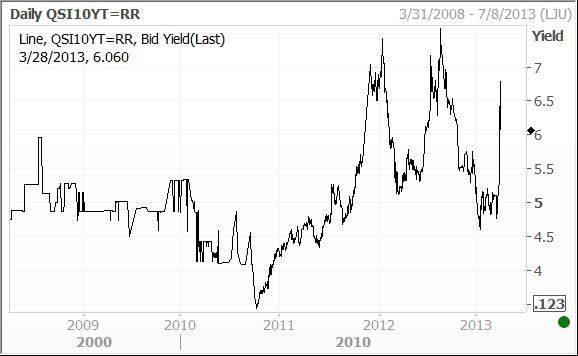

The yield on Slovenia's 10-year note have jumped over 100 basis points in the last week or so, rising to 6.8 percent -- the highest level since September.

The focus of market pressures on Slovenia is unsurprising. Although the banking sector is much smaller than Cyprus’, banks’ nonperforming loans have risen to 15 percent of total assets, with the ratio in the three largest banks topping 20 percent. These numbers may increase further given that the economy is set to contract by at least 2 percent this year, following a fall of 2.3 percent in 2012.

“Banks are under severe distress,” noted International Monetary Fund in its annual health check on the country. The IMF recently estimated that the government needs to recapitalize the banks to the tune of at least €1 billion, or 3 percent of GDP.

But if bond yields stay high, raising that kind of money at a reasonable price could be difficult. That may force Slovenia to look to the European Central Bank, or the European Commission, or the IMF — or all of them — for a loan with below-market interest rates. In other words, a bailout.

New Prime Minister Alenka Bratusek told the Slovene parliament on Wednesday that the fears are overblown and that Slovenia won't need international aid. “Our banking system is stable and safe. Comparisons with Cyprus aren’t valid. Deposits are safe and the government is guaranteeing them.”

Malta

Malta may also come under the spotlight. Its financial services sector is eight times its GDP, about the same size as Cyprus’ and Ireland’s before its crash.

However, Malta's central bank governor, Josef Bonnici, warned on Wednesday that comparing Malta with Cyprus would be misleading.

He told the Times of Malta that the assets of the country's major banks amounted to "just below 300 percent” of GDP, which by international standards was "within normal limits." Bonnici also highlighted the exceptional nature of Cypriot banks' losses on Greek government debt. "Maltese domestic banks have limited exposure to securities issued by the program countries," he added.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg could also suffer a loss of faith in its banks given that bank assets amount to over 2000 percent of GDP -- by far the highest in the euro zone.

Capital Economics analyst James Howat points out that Luxembourg's banking sector consists largely of subsidiaries and branches of foreign banks, so that significant support might be expected from mother banks and, ultimately, the governments of those mother banks, in the event of a crisis.

Just 8 percent of Luxembourg's banking assets are held by domestic banks, compared with 71 percent for Cyprus, according to ECB data. Luxembourg's premier, Jean-Claude Juncker, said Cyprus was a “special case” and that Luxembourg was completely different.

“We do not attract Russian money to Luxembourg with high interest rates. The Luxembourg financial center is based on several pillars. We are characterized by the breadth of our product range; we are an active participant in the international credit business,” Juncker said.

“There are no parallels between Cyprus and Luxembourg, and we do not allow such parallels to be imposed upon us,” he said.

The Luxembourg government also issued a two-page statement insisting that its economy is nothing like Cyprus'. In a statement, it said:

As a matter of principle, Luxembourg is concerned about recent statements and declarations that were made since the crisis in Cyprus sharpened by (1) making comparisons between the business model of international financial sectors in the euro area and by (2) making more general assessments of the size of the financial sector in relation to a country’s GDP and the alleged risks this poses for economic and fiscal sustainability.

[...] As regards the business model of the financial sector in Luxembourg, it is quintessentially an international one within the euro area, acting as an important gateway for the euro area by attracting investments and thus contributing to the general competitiveness of all Member States.

Estonia and Slovakia

Estonia and Slovakia are the two other small euro zone members. Although Estonia’s banks are reliant on foreign funding, this has come from historically stable Nordic sources, and the country’s fiscal position is very strong. Slovakia, in turn, has the smallest banking sector in the euro zone, and the economy has grown robustly throughout the euro zone crisis.

“That said, should market concerns toward smaller economies in general continue to intensify in the wake of the Cyprus bailout, both countries could still be vulnerable to contagion effects,” Capital Economics’ Howat said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.