Dallas Fed’s Fisher Says No to QE3, Touts Texas and Mexico as Examples

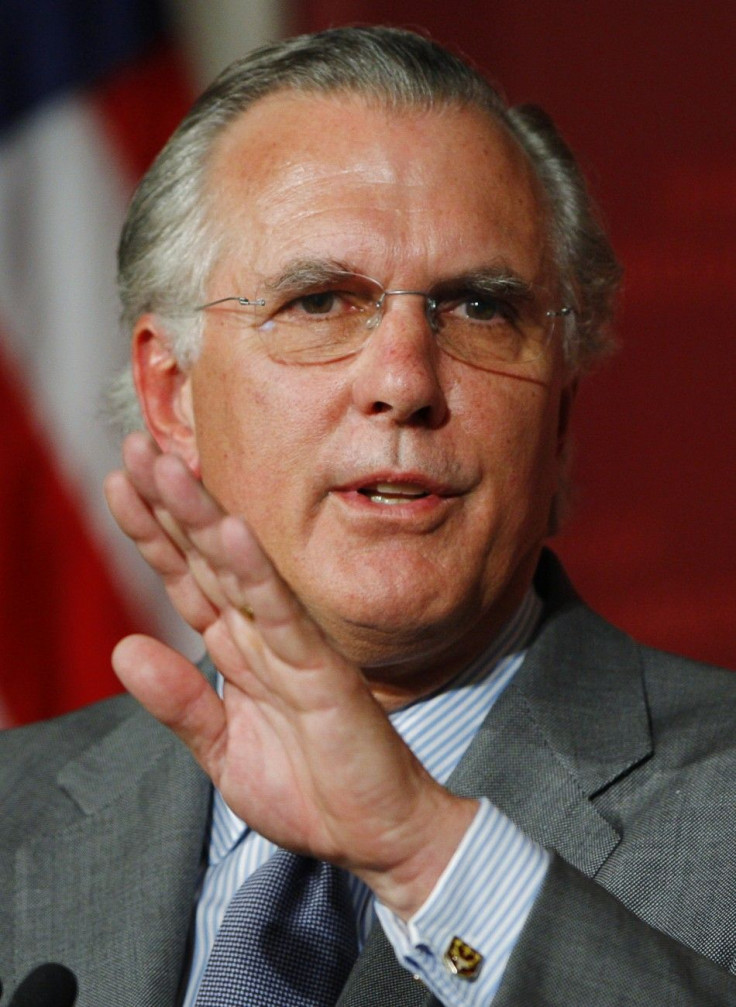

Decrying Wall Street calls for a third round of monetary expansion, or quantitative easing (QE3), the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas urged U.S. lawmakers Monday to follow the examples of Mexico, where fiscal discipline is the norm, and Texas, where the regulatory regime is far from punitive.

I am personally perplexed by the continued preoccupation, bordering upon fetish, that Wall Street exhibits regarding the potential for further monetary accommodation -- the so-called QE3, or third round of quantitative easing, Richard Fisher said.

Although data indicates that growth and job prospects will improve in 2012, the economic outlook of the United States is hardly 'robust' and economic improvement is limited by the fiscal and regulatory misfeasance of Congress and the executive branch, Fisher stated.

As demonstrated by the fiscal posture of Mexico, a nation can effect budgetary discipline and still have growth, Fisher said. Mexico has many problems. But on the fiscal front, the country is outperforming the United States. Mexico's government has developed and implemented better macroeconomic policy than has the U.S. government.

An essential aspect of Mexico's macroeconomic policy that has been missing in the U.S is the existence of a federal budget that reflects deficit control.

Mexico actually has a federal budget. We haven't had one for almost three years. Furthermore, the Mexican Congress has imposed a balanced-budget rule, so ... Mexico ran a budget deficit of only 2.5 percent in 2011 compared with 8.7 percent in the U.S., Fisher said.

While U.S. industrial production has not yet passed its pre-recession peak, Mexico's industrial production reached that point in 2010, a result that is at least partially the result of the Mexican government's budgetary policy, Fisher said.

Texas also should be a model for U.S. lawmakers.

As demonstrated by the relative and continued, inexorable outperformance by Texas -- which is affected by the same monetary policy as are all of the other 49 states -- the key to harnessing the monetary accommodation provided by the Fed lies in the hands of our fiscal and regulatory authorities, the Congress working with the executive branch.

In a comparison of all 12 Federal Reserve districts for the period 2008 to 2011, the Dallas district has outperformed every other state in the country except for Alaska and North Dakota in terms of job creation. Fisher argues that because every state is subject to the same federal monetary policy as administered through the Federal Reserve system, the superior performance of the Dallas district, where 96 percent of economic production comes from within the state of Texas, is the result of some economic trait unique to Texas.

Discounting the 30,000 jobs created in Texas by the oil and gas industries, other sectors gained more jobs than the oil and gas sector and its support functions in 2011: 58,000 jobs were added in professional and business services; nearly 46,000 in education and health services; and more than 41,000 in leisure and hospitality. Manufacturing -- which accounts for approximately 8 percent of total Texas employment -- added over 27,000 jobs, Fisher said.

Ultimately, higher levels of job creation and economic growth in Texas are the result of attractive tax and regulatory environments, Fisher said.

Essentially, businesses are attracted to Texas because the regulatory and tax environment reduce the costs of doing business. Firms and jobs will go to where it is easiest to do business -- not where it is less convenient and more costly, Fisher said while comparing regulatory challenges between Texas and California and New York.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.