The Death Of Lehman Brothers: What Went Wrong, Who Paid The Price And Who Remained Unscathed Through The Eyes Of Former Vice-President

“Nothing in this world can so violently distort a man’s judgment than the sight of his neighbor getting rich.” -- Attributed to J.P. Morgan, 1907

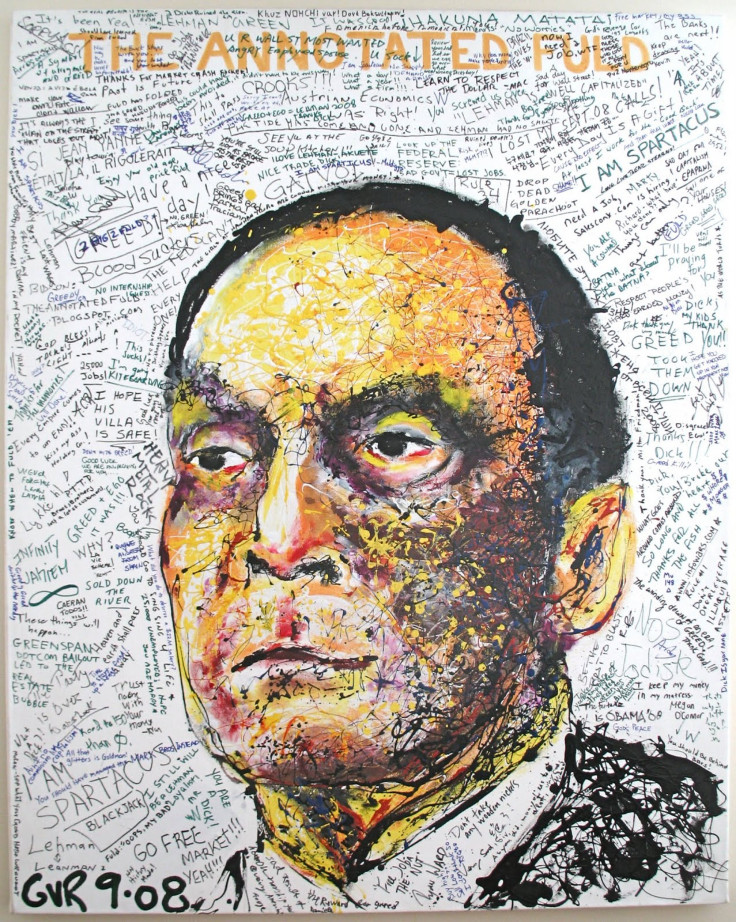

One of the lighter comments on Geoffrey Raymond’s portrait of much-reviled Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. CEO Richard S. Fuld Jr. was “So long, and thanks for all the fish” -- a reference to the book of the same name by Douglas Adams and what the dolphins say in the book as they depart for another planet just before it gets demolished to make way for a hyperspace bypass. Today, it simply means “Goodbye.”

Raymond’s portrait, titled “The Annotated Fuld,” was created with help from former employees of Lehman Brothers as they walked out of their old office building for the final time. After painting the portrait, Raymond asked the departing employees to contribute by writing how they felt about Lehman’s collapse -- and their old boss. The portrait, a mix of surrealism and graffiti, illustrates how many will remember the man most blamed for one of the worst business disasters in history. But it isn’t the only graphic evidence of distaste for Fuld.

Inside the former Lehman Brothers building, on the third floor of 745 Seventh Ave., is a 100-foot-long wall that similarly was scrawled with depictions -- most of them insulting -- of the leaders of the once-great Lehman Brothers. The wall of shame, as it was called, featured Fuld arm-in-arm with Chief Operating Officer Joseph M. Gregory: Both wore tuxedos, with the slogan “dumb and dumber” written beneath. The impromptu mural had members of the board of directors depicted as pensioners, propped upright and using walkers, accompanied with the caption “voting in Braille only.” Even Henry Paulson, U.S. secretary of the treasury from 2006 to 2009, didn’t escape the lampooning. He was portrayed as sitting on Fuld’s head, with the line, “We have a huge brand with treasury.”

Those depictions illustrated the final days of Lehman Brothers, which filed for bankruptcy protection in 2008. They were the last acts in a kind of angry celebration for a staff that had been consigned to the fate of seeing the 158-year-old institution crumble to almost nothing, while losing their jobs in the process. Within a week, plans to split the bank up were going through the courts.

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge James M. Peck, seemingly stunned by the magnitude of the bankruptcy after a seven-hour hearing, issued a final statement just before he allowed the core elements of Lehman to be sold to Barclays PLC (NYSE:BCS) for about $1.37 billion. “I have to approve this transaction because it is the only available transaction,” Reuters quoted Peck as saying in open court. “Lehman Brothers became a victim, in effect the only true icon to fall in a tsunami that has befallen the credit markets. This is the most momentous bankruptcy hearing I’ve ever sat through. It can never be deemed precedent for future cases. It’s hard for me to imagine a similar emergency.”

In the U.S., the term collateralized debt obligation will never escape the minds of those responsible for the financial crisis or of those who lost everything in its collapse. At the core of the problem were high-reward, high-risk investments -- the kind Lehman Brothers made day in and day out.

“At Lehman, there were 24,992 people making money and eight guys losing it,” said Lawrence G. McDonald, the co-author of the New York Times best-seller “A Colossal Failure of Common Sense: The Inside Story of the Collapse of Lehman Brothers” and a former vice president at Lehman Brothers. “In other words, most people think Lehman had this reckless culture, but most traders were good traders and the people that sunk the firm were those that created those concentrated positions.”

McDonald, 47, who worked at Lehman for four years, said the company had more than 35 percent of its net tangible equity in three commercial real-estate investments -- essentially, he said, making Lehman a massive private-equity trust with an investment bank on the side. “Most of the employees had no idea that the firm was so concentrated in so few investments, and to this day that was one of the most reckless endeavors of the financial crisis -- that massive concentration of risk,” McDonald said.

As one of the self-proclaimed “revolutionaries” inside the bank and a member of a team that was trying to “stop the madness,” in his words, McDonald, who recalled his experiences, including his recollection of the wall of shame, to International Business Times, said he was pushed out for trying to right the wrongs of years of poor financial management.

In McDonald’s book, published in 12 languages to date, there is a line that perhaps sums up the problems within Lehman and offers a clear metaphor to explain how families lost their homes and savings: “It was the Ivory Tower. Lehman was never rotten at the core, that’s where all the beauty was -- she was rotten at the head.”

Lehman’s death was quick, but the building that will forever be associated with the bank never died: It was sold and given a new life under the stewardship of Barclays just one day after Lehman filed for bankruptcy protection on Sept. 15, 2008. Physical assets go quickly because they have a measured value based upon a number of transparent factors, such as location, square footage, age, quality of craftsmanship, etc.

Nobody could argue with the building’s value: It had been agreed upon in the most transparent of ways, by an independent real-estate expert who had nothing to gain from the transaction and had to follow industry-set rules. Most of Lehman’s assets were not so transparent and hidden away in complex transactions all over the world, many vaguely following the rules, if there were any even set.

And it was the very idea of transparency -- or the lack of it -- that, in McDonald’s opinion, sank the bank. “Where they’ve failed is, here we are five years later, and there isn’t a lot of transparency in terms of what is on the balance sheets, so you have trillions of bank deposits sitting on top of very opaque black-box type investments,” he said.

What Happened To The Remains?

Across the world, similar court decisions were being made due to Lehman’s global reach, demonstrating the huge significance of Lehman’s destruction. On the same day that the building was sold, deals were put in place for Barclays to relieve Lehman of its entities known as Lehman Brothers Canada Inc., Lehman Brothers Sudamerica SA and Lehman Brothers Uruguay, as well as its private business known as Investment Management, for high-net-worth individuals. These businesses had clients with deposits and savings, and some of them were not in the same poor shape as Lehman’s destroyed U.S. businesses, but ultimately were the assets of the broken mother ship and had to be sold off to service its debt.

The Japanese Nomura Holdings Inc. (NYSE:NMR) stepped in to take on assets in the Asia-Pacific region, including Japan, Hong Kong and Australia, for $225 million. The day afterward, Nomura announced it would take over Lehman’s European and Middle East investment-banking and equities businesses for just $2. The low price was to ensure that it kept on the employees. However, Nomura has said it will have to shed five percent of its workforce in the coming year, further showing how the Lehman issue continues to trundle along.

The rest -- Lehman’s real value -- was a complicated array of broken promises with values that were difficult to figure out, mostly because they are not tangible assets. Wrapped in more than 2,000 subsidiaries are tens of thousands of toxic deals that have to be untangled, straightened out and sold. To bankers, these are numbers on a screen, profits or losses in the margins, but to someone, somewhere, it’s all of a home or life savings, and people will have to wait years to retrieve only a small portion of it.

Like a kind of Frankenstein monster, Lehman survives on the periphery of public knowledge, on two floors of the Time & Life Building in midtown Manhattan after quietly exiting bankruptcy in March of last year. Its goal now is to generate as much money as possible to pay off its creditors. Even with its reputation in tatters and vastly reduced staff, Lehman is making good on some payments, beginning with $22.5 billion in April 2012 and $47.2 billion since then. At the end of 2012, Lehman had $21 billion in cash.

The company mostly consists of a huge legal department, although it still has a normally functioning trading floor. The people left at Lehman are no longer asked to make profits at all costs. Instead, they are charged primarily with trying to fix the wrongs of the past, as McDonald said he tried to do.

The legal department is thriving as it deals with more than 60,000 claims and tries to pay back the $360 billion the company owes, although it will only have to pay back 18 percent of that value, or 18 cents on the dollar (some analysts say the company could raise as much as 24 cents on the dollar). Its only mandate is to follow the instructions of a 791-page legal document that lists every one of its unfulfilled legal promises, most of which are financial in nature. Investors receive different amounts based on the type of loan they extended to Lehman. For examples, Lehman’s commercial-paper subsidiary will get 56 cents on the dollar and those who bought a parent company bond will only receive about 20 cents on the same basis. Some creditors in the U.K. are entitled to 100 percent plus eight percent interest.

In a similar sense to how Lehman crashed in 2008 and the U.S economy entered a period of decline, both appear to have rebounded to some extent. The one-time poster child of financial excesses and unnecessary risk has, in an odd and paradoxical way, become the poster child for survival and dogged determination to succeed, even if it is just for a limited period.

Lehman, only likely to exist until 2017 (the year it is supposed to have sold off its incredibly large and complex portfolio of toxic assets) employs a vast array of young up-and-comers who are gaining valuable experience within this highly unlikely company -- essentially working themselves out of a job. But in that way the company is transforming itself, creating new assets as it deals with the loss of old ones -- much like the new American economy.

Winners And Losers

According to McDonald, one of the biggest problems within Lehman was that Fuld ruled supreme for 18 years. In McDonald’s book, Fuld was fearful of the very talented people below him, and in a very Machiavellian way had his right-hand man Joe Gregory take out anyone who posed a threat. Fuld’s own agenda -- remaining as emperor -- eventually cost him his kingdom as he got rid of the very minds that could have helped him turn it all around.

“Look at Goldman Sachs -- they typically have a partnership and are much more controlled and are controlled by the partners,” McDonald said. “For example, Goldman would never have a CEO in there for 18 years. They never would. There’s a constant turnover. There’s a reason we have term limits, and this was always a thing with partnerships. Lehman used to work this way, but in the Eighties, early Nineties, it changed, and they become public, and that’s how someone like Fuld gets to stay for all those years.”

McDonald also said the average age of the board was around 70, meaning it largely reflected a different era of banking. Athough they had come from a different era, they benefited from the newest age of banking. They sat in their comfortable seats, some for as long as 18 years, and watched the bank amass huge profits by gobbling up assets across the world and making risky bets.

Perhaps the starkest contrast between so-called ordinary people and these powerful figures was in the realm of completed foreclosures, which in the U.S. reached 4 million between 2007 and 2011, and more than 8 million since. By September of last year, 57,000 foreclosures were being completed every month.

Meanwhile, Fuld ensured that he would suffer no such fate. On Nov. 10, 2008, Fuld transferred ownership of his Florida mansion to his wife Kathleen for $100 to protect the house from potential legal actions against him, as noted by the Telegraph in the U.K. The couple had bought the house four years earlier for $13.75 million. In 2009, he sold his Park Avenue apartment for $25.87 million, but kept his mansion in Greenwich, Conn., his ranch in Sun Valley, Idaho, and his five-bedroom home in Jupiter Island, Fla.

Although he is reported to have taken home $529 million in pay and bonuses during his time at Lehman, according to a former general counsul, Fuld on Sept. 17, 2008, sold 2.87 million Lehman shares, making just $639 from what was worth roughly $169 million a year earlier. In April 2009, he announced a position at Matrix Advisors, where he reportedly asked for a $10,000 monthly retainer and stock options from Ecologic, one of his clients. But last year he lost his securities license and found himself in the financial wilderness.

Fuld did not respond to emails or phone messages from the International Business Times.

‘They Took Lehman’s Head, Put It Under Water And Watched For The Bubbles’

As the crisis began to close in on Fuld and the bank, a last-ditch deal was cut to sell Lehman to Barclays of London, but the deal was subsequently vetoed by the Bank of England and the U.K.’s Financial Services Authority. The final throw of the dice was to bail the bank out with U.S. taxpayer money, but that option was rejected at the final hour in an apparent standoff with the top CEOs of America’s banks and the Federal Reserve.

McDonald claimed that Lehman was the subject of unprecedented political intervention from above by people deciding who to save and who to drown. “In the history of capitalism, the free market makes those decisions, not politicians. But the problem is, capitalism does not work without transparency. When it’s hidden, it’s like a blood clot. In true capitalism, capital flows to the healthiest banks,” McDonald said.

As McDonald indicated, the main problem of Lehman’s collapse is that the response to its demise and the troubled financial system was, ultimately, determined not by technical regulation, but by politics. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. has received new powers that enable it to take over a large, troubled holding company, sell off the good parts and carefully manage its dissolution. However, these new powers can only be used after receiving the consent of the U.S. treasury secretary. And it can only save institutions that are systematically important, a designation determined by whichever politician holds the relevant position in office.

Today, the FDIC is working on finalizing its new powers, but, given that the ultimate decisions will be made by politicians, lobbying has grown by nearly 60 percent, meaning bankers will have to be closer than ever to politicians to get what they want.

“These guys were playing god in 2007 and 2008, picking winners and losers,” McDonald said. “Bear had much more leverage and Lehman was far riskier,” he added, suggesting that Lehman needed the help, not Bear Stearns. “[Timothy] Geithner and Paulson claim that they hadn’t set up the necessary firewalls around the time of Bear Stearns, so that’s why they were so motivated to create their merger with JPMorgan Chase & Co. [NYSE:JPM]. Lehman was so much more of a deadly risk.”

According to an account in the book “Crash of the Titans: Greed, Hubris, the Fall of Merrill Lynch, and the Near-Collapse of Bank of America,” by Greg Farrell, Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, Federal Reserve Bank of New York President Timothy Geithner sat down on Sept. 12, 2008, with the top executives on Wall Street, including Jamie Dimon, Lloyd Blankfein, Vikram Pandit and John Mack, along with representatives of top foreign banks -- the type of people who had gotten to the top through tireless effort and mental toughness and who were about to be pushed to their limits.

Geithner began by explaining that Lehman’s failure would be catastrophic to the markets and that it was in the best interest of the banks involved to sort out the crisis together if they were to prevent such a failure. However, it was Geithner’s next warning that sent shock waves through the room. The government would not be putting up any money to bail the bank out. Many of the CEOs in the room, men who had made careers out of bullying their ways to the top, were not about to fall for what they considered to be a bluff.

It wasn’t a bluff, and a similar threat by Paulson didn’t change the feeling among the CEOs.

‘They Really Took A Massive Gamble By Letting Lehman Fail’

McDonald believes Lehman’s collapse could have triggered a run on money-market firms and banks. As markets froze and interbank lending came to a halt, troubled companies had few places to turn. The General Electric Co. (NYSE:GE) and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. (NYSE:GS) both took loans from Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (NYSE:BRK.A) in acts of desperation before being forced to turn to the Fed.

“The money was so tight that ATMs could have stopped working. It could have really gotten out of control. Paulson was seen as a hero, and a lot of the things he did were brilliant to get us out of the thing,” McDonald said.

Since the collapse, many of Lehman’s executives went on to work at Barclays, but the top execs have largely disappeared from public view.

Former CFO Callan, who only lasted about six months in the job and resigned four months before the collapse, briefly worked at Credit Suisse Group AG (NYSE:CS), but took what turned out to be a permanent leave of absence after allegedly suffering an emotional breakdown, as indicated by Fortune.

Fuld’s sidekick Gregory, former COO of Lehman, was known in the company for two things: being Dick’s sidekick, and living extravagantly. Vanity Fair reported former co-workers’ memories of him actually leaving $1,800 tips on $200 lunch bills and the local soccer field he underwrote when one of his daughters took a liking to the sport. He was well-known for flying his helicopter and seaplane to and from his home in Long Island, although he sold both later in 2008, after resigning in September. Since then, he has been famous for selling other big-ticket items, including a mansion in Bridgehampton for $20.5 million.

Those former executives who stalked the halls of what is now the Barclays building, who had their own elevators and were widely seen as above other employees, may not have been aware of the havoc they were causing throughout the world. But banking was transformed by a toxic culture at Lehman, especially in the case of Fuld, according to McDonald, who claims the ex-CEO lost sight of his purpose as a banker, and was caught up in the obsession of making money.

Fuld will always be remembered for destroying Lehman Brothers -- a legacy he can’t escape.

As Raymond’s painting suggests, whatever suffering he has experienced is magnified by the suffering of others, including his former employees and all the families who lost their homes.

And Fuld’s company, having set a benchmark for success in banking, is now synonymous with failure.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.