Despite Falling US Unemployment, Numbers Of Long-Term Unemployed And Those Who’ve Given Up On Work Remain High

There was a bright side to Mike Chase’s layoff. He spent more time with his daughter before she went off to college last year — and his wife is gainfully employed as a physical therapist. But the 56 year old has been trying to find a new job since a series of 2011 cuts at Bedford, Massachusetts-based Progress Software Corp. pushed him into the ranks of the unemployed.

“I loved it,” he said about his job as a briefing specialist who organized meetings between the company and its clients, a profession he’s had since the late 1980s at different companies, including Hewlett-Packard. “But business doesn’t always go on love.”

In 2010 Progress announced it would trim up to 9 percent of its global workforce, and Chase ended up one of the casualties of the company’s corporate restructuring plan. Ever since, Chase has tried to find work, sending out applications, joining professional networking, even volunteering his skills to help other job seekers. To no avail.

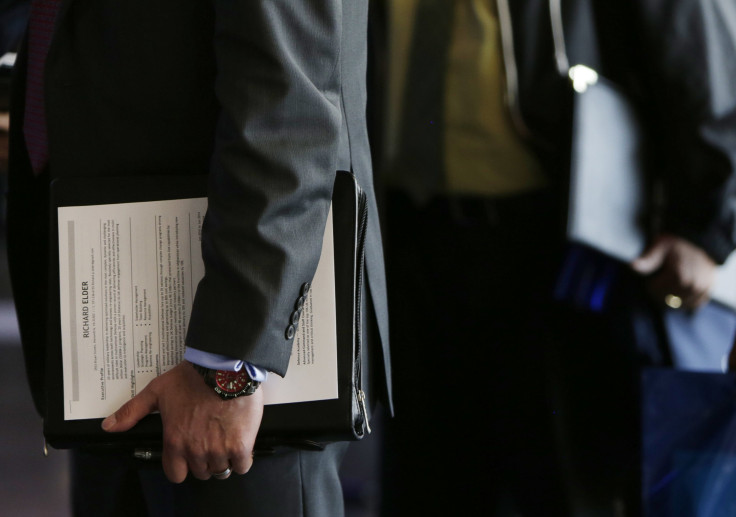

On Friday, the U.S. Labor Department said the country’s jobless rate dropped from 5.8 percent in November to 5.6 percent last month, the lowest rate since June 2008. The report showed 2014 to be the best year for job growth since 1999, but as the top-line numbers improve, deep problems persist in the U.S. job market. Businesses are creating jobs, but many of them are part-time or temporary positions. At the same time, the number of people who are able to work but have dropped out of the workforce remains at a historically high level. And the portion of Americans considered to be “long-term unemployed” remains unusually high.

Chase is among them. He’s one of the 2.79 million working-age Americans who have been actively seeking employment for 27 weeks or longer, a number that has been gradually dropping from an all-time peak of 6.8 million in April 2010. Still, the number is more than twice as high as levels seen before the Great Recession.

In an economy that often discriminates against older workers, Chase, in his mid-50s, is at risk of falling from one dire statistical category—the long-term unemployed — to an even more dire classification — those who’ve permanently given up the search for work. In December, the so-called labor force participation rate dipped to 62.7 percent, the same rate as in September when the proportion of American adults participating in the labor force hit a nearly 37-year low.

"When people leave the labor force, you are slowing growth," said Bill Spriggs, chief economist at the AFL-CIO, the largest U.S. labor federation. "And this waste affects us all, because we have a smaller economy than we should have. This gap between where growth is and where it could be is in the trillions of dollars, it’s bigger than the fiscal deficit.”

Faith Hendricks, 47, is one of those 93.5 million working-age Americans who have been out of work so long they aren’t included in the unemployment figure. She’s also one of the so-called “marginally attached” Americans in the labor force – people who searched for work over the past year but haven’t looked for work in the past four weeks.

Hendricks hasn’t looked for work since last summer after losing her job in May 2013 as an office assistant at a shipping company in Shreveport, Louisiana. Living in subsidized housing with her daughter who works at a local hotel and casino, Hendricks says she’d be homeless without help from her family and her church that stocked her refrigerator over the holidays.

“My church has been very supportive,” she said. “They’ve given me food, but you start to feel like it’s been too long accepting charity. They say the economy is getting better, but that don’t mean it’s been easy to find work. It hasn’t been easy for me.”

While the unemployment figures released Friday show the U.S. economy is improving and more people are being hired, economists say it’s only a small part of the larger economic picture. Until more discouraged workers like Hendricks and long-term jobless people like Chase find jobs, the U.S. economy can’t take off.

“There are a lot of workers out there who can do jobs,” says Spriggs. “We’re wasting our nation’s most valuable resource by not hiring them.”

Kathleen Caulderwood contributed to this report.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.