Drones Are Big Hit At Paris Police Expo As Europeans Seek More High-Tech Equipment To Combat Terror

PARIS -- For many years, it was the military, not local police, who had access to drones. Not anymore. Police teams want them too -- especially now.

Less than a week after armed gunmen launched a coordinated attack on six sites around Paris, including restaurants, the Stade de France soccer venue and the 1,500-capacity Bataclan concert hall, many police forces are looking to beef up their anti-terrorism and surveillance arsenals. And according to several drone manufacturers, many police forces are turning to them.

Yves Degroote, the international sales manager for AirRobot, a surveillance drone company based in Germany, said he has received dozens of inquiries from around the world since the attacks last Friday. "The emails keep coming in over the last few days,” he said. “To be honest, I'm a little behind. The demand is increasing."

Degroote said police have wanted to use his company's drones for years, but typical local police budgets put them out of reach. AirRobot’s drones, first manufactured for use by the German military, cost $45,000 to $90,000 each. In the wake of the Paris attacks, however, Degroote thinks police budgets may increase.

“Now, after a few terrible incidents, budgets are increasing,” he said. “In two [or] three months, this effect will die [down] a little bit."

Degroote spoke in front of his booth at Milipol, Europe’s largest military and police exhibition, which is taking place this week in Paris. In light of the recent attacks, more European countries may be open to the idea of militarized police forces. And American firms that produce these products are expecting a boom in demand.

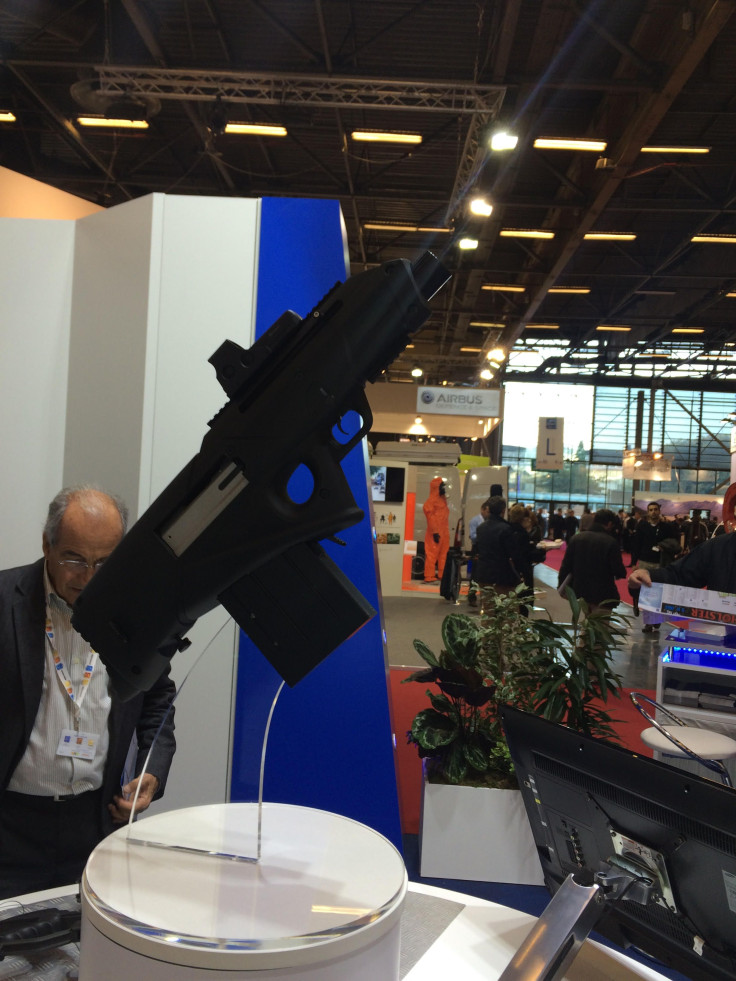

In previous years, the event has focused on more traditional weapons and devices, like tanks, assault rifles and body scanners. Those are still on display, but this year, drones have taken center stage. Conference organizers have made drones, in addition to anti-terrorism, cybersecurity, safe cities and major risks, among the main "highlights" of the event. (A drone, in fact, is the sole decoration on this year’s Milipol logo.)

Jeremy Korwin-Zmijowski, an employee at the 1-year-old French drone startup Aeraccess, said the company struck a deal with the French national police earlier this year to build a customizable drone, which starts at $50,000. The drones, he said, are becoming cheaper and stronger as the technology advances, and can be outfitted with a variety of tools or weapons weighing as much as 2 kilograms.

"You have to see the drone like a host," he said. "And you have to give it a job." Among those jobs, he said, are surveillance, communication and even firing tear gas canisters.

Korwin-Zmijowski said his company has yet to receive a request from police for a drone armed with a gun, but he said it's possible. "You can do what you want," he said, noting the latest attacks will "accelerate the sale cycle."

Another exhibitor, Alsetex, displayed a new type of counterterrorism drone called the “Cougar” that can shoot tear gas canisters into an unruly crowd. One brochure being handed out to attendees read: “Equipping [drones] with a launcher payload provides an alternative approach to crowd control missions.”

Company officials would not comment on its cost, use or customers. However, a natural question lingers: What happens if these weaponized drones end up in the hands of criminals or terrorists?

Drone companies have that covered, too.

Some of the tech firms at Milipol were also peddling guns to shoot drones from the sky. Alsetex, which is known in the gun industry for its grenade launchers, now sells a product used to launch specially designed bullets at illicit drones that may be hovering.

Another company, Dedrone, based in Germany, sells a product that uses a mix of visual, acoustic and ultrasonic sensors to locate drones hidden above the clouds. “The drones available today are no longer simply toys for kids or hobbyists, but are increasingly being used for spying, drug-smuggling and industrial espionage,” a company brochure reads. “To make matters worse, drones can be easily outfitted with weapons or explosives by anyone who wishes to physically harm rivals or governments."

Of course, many people -- especially privacy advocates -- might bristle at the notion that their local police departments will be deploying surveillance or weaponized drones above their backyards. The American Civil Liberties Union, for instance, published an article last summer titled, “Five Reasons Armed Domestic Drones Are a Terrible Idea.”

But at Milipol, which is frequented by government officials and members of law enforcement from around the world, concerns over privacy take a back seat to concerns over terrorism.

Yves Degroote, the international sales manager for AirRobot, agreed people might be turned off by the idea police are using surveillance drones over their homes.

“But I think it's just going to happen,” he said. “It's inevitable."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.