Drones Being Used By Conservationists To Stop Poachers, Protect Endangered Species

All too often, forest rangers policing wild regions of Africa or India learn poachers are in an area only after the fact, when they come across the remains of a skinned tiger or an elephant graveyard. The mainstream availability of drones, however, has made it possible for authorities to respond faster and in some cases to fend off poachers entirely by watching them in real time from the skies above.

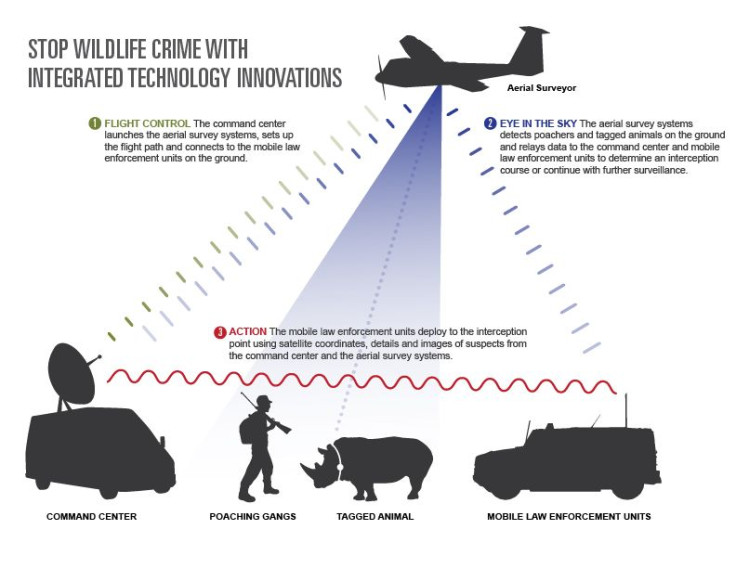

With the help of tech-savvy conservation groups, a growing number of international governments are rolling out pilot programs that rely on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to monitor animal migration habits, keep watch over dwindling endangered species numbers and, perhaps most importantly, curb illegal hunting.

Fewer than 3,000 wild tigers still roam free in the world, a figure that only became more startling when the Wildlife Protection Society of India announced last year that illegal poaching was at its highest level in the past seven years. The problem isn’t easily solved, with criminal gangs trying to fill a seemingly insatiable demand for fur and poor villagers killing tigers as revenge for killing their cows. But, starting in January, officials in 10 Indian regions where tigers are most at risk will be able to police the areas from above.

“UAVs provide critical aerial surveillance that span farther distances than the human eye can see, and can detect body heat from humans and animals with infrared camera systems,” said Colby Loucks, a senior director of wildlife conservation at the World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF). “This is very important, especially when you consider that poachers typically strike at night to go undetected. The UAV in the sky provides the coverage and the data that the rangers need to respond to the threat directly.”

In addition to keeping track of a population’s numbers, UAVs can benefit ranger morale. Rangers charged with protecting Nepal’s Chitwan National Park, in particular, are forced to consider not only machine gun-toting poachers but various jungle villagers paid by the poachers to disrupt conservation efforts and investigations.

In an attempt to help officials avoid finding themselves encircled by angry gunmen, Lian Pin Koh, a cofounder of the nonprofit Conservation Drones, designed a UAV with a 33-inch wingspan and equipped with a GoPro camera that scans the area below. Koh, an environmentalist who designed the device when he was unable to examine orangutan nests hanging in the trees, told the International Business Times he expects that drones will soon be the only way to effectively observe species.

"Nowadays we take for granted the use of mobile phones, handheld GPS devices and even radio-tracking animal collars by park rangers. these devices must have been regarded as a novelty when they were first introducted in the '80s and '90s," he said.

"I am quite sure there must have been initial resistance to their use in conservation because people were just unfamiliar with each new technology. I believe that it is only a matter of time before drones become part of the toolkit of park rangers to help them do their job more effectively."

Not everyone agrees. The U.S. National Park Service, which prohibits visitors from using drones and recently announced that a tourist crashed a camera-equipped drone into the largest hot spring at Yellowstone National Park, has yet to deploy drones in any significant way, though UAVs were used to help firefighters slow down the massive Rim fire at Yosemite National Park last year.

“People are looking at the possibility of using them in a way that would help with administrative functions such as firefighting or wildlife purposes,” said Jackie Scaggs, a spokeswoman for Grand Teton National Park, which relies heavily on traditional aircraft for search and rescue missions. “We also do population estimates on some of the animals such as elk and bison. For instance, we’ll use helicopters to help with the annual census of the wolf population.”

Others have voiced familiar concerns about privacy and the sheer annoyance that comes with UAVs flying overhead, disturbing what was a peaceful moment outside only moments before. Yet David Wilkie, a director of Conservation Support for the Wildlife conservation Society, told Smithsonian that increased affordability, combined with the massive demand for tiger fur, bones, elephant tusks, rhinoceros horns and the like, may make use of drones inevitable.

"The pressure on natural resources in almost all conservation spaces on the planet is increasing," Wilkie said. "How do you move beyond enforcing the law and catching guys with ivory to preventing them from shooting elephants in the first place? Can we use drones to do that? That gets people's ears pricked up and they begin to think, 'Ooh my gosh, this could really be a game changer.'"

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.