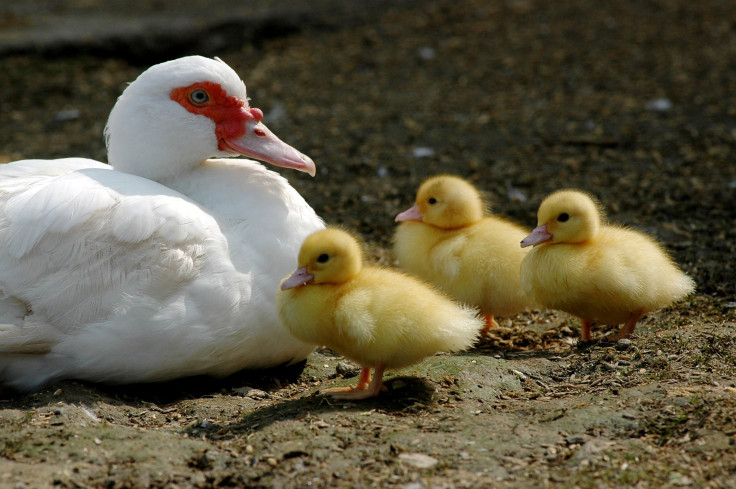

Ducklings Are Capable Of Abstract Thoughts, Can Distinguish ‘Same’ From ‘Different,’ Oxford Study Finds

The ability to deal with abstract concepts, including patterns of “same” and “different,” is not uniquely human. With extensive training, even animals are capable of demonstrating the same. But, results of a new study show that the newly hatched ducklings can be so smart that they can make a distinction between "same" and "different" — without any training.

As part of the study, published in the journal Science on Friday, professor Alex Kacelnik of the University of Oxford and his student Antone Martinho III performed a behavioral test with ducklings that can quickly learn the traits of their mothers within hours of hatching — a process known as imprinting. The researchers found that the newly hatched mallards can do more than we thought they could.

“In a way, imprinting appears to be simple," the Atlantic quoted Kacelnik as saying. “But it’s extremely complex because mum is an extremely complex collection of properties. So what is it that a young animal stores in its brain to recognize the identity of its mother?”

In their quest to find the answer, the researchers presented the newborn ducklings with a pair of objects that were either the same or different in shape or color. When the ducklings were shown new pairs of objects later, they surprisingly followed pairs exhibiting the same relation on which they had originally imprinted.

According to Kacelnik, the ducklings were imprinting on the concepts of “same” and “different,” rather than on a specific shape or color. In short, “they were abstracting properties,” Kacelnik said.

In a related commentary, Edward Wasserman from the University of Iowa, who was not part of the research team, said that the ducklings were exposed to only a single pair of stimuli, therefore they actually outperform human babies. According to Wasserman, 7-month-old toddlers can also distinguish between "same" and "different" without any supervision, but only after seeing at least four pairs of objects, the Atlantic reported.

"This study is important for at least three reasons," Wasserman said. "First ... it indicates that animals not generally believed to be especially intelligent are capable of abstract thought. Second, even very young animals may be able to evidence behavioral signs of abstract thinking. And, third, reliable behavioral signs of abstract relational thinking can be obtained without deploying explicit reward-and-punishment procedures."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.