Egypt’s Conflict: After The Military Government’s Violent Crackdown There Seems To Be No Safe Side For U.S. To Be On

CAIRO, Egypt -- “In two-three days, there will be no Muslim Brotherhood,” proclaimed street vendor Mahmoud Nasser, a day after the Egyptian military’s bloody attack this week on protesters who support ousted President Mohamed Morsi. “The Muslim Brotherhood were killing people, and America supported them,” he added, bitterly.

One might also argue that U.S. military aid enabled the ongoing attacks on the Muslim Brotherhood. But complexity and nuance are among the first casualties of violent conflict.

In fact, the U.S. has sent an average of $1.5 billion annually in aid to the Egyptian military since 1987 -- to forces under the command of former President Hosni Mubarak, who was ousted during the 2011 uprising, and to those under the command of recently ousted President Morsi, who was supported by the Muslim Brotherhood. The military, in turn, has backed the popular ouster of Morsi and the violent crackdown on Muslim Brotherhood members and supporters.

After weeks of protests and negotiations, Egypt’s security forces on Wednesday moved to disperse two major sit-ins and several smaller protests in support of Morsi, and the interim government issued a state of emergency and curfew. The military’s latest move, which came weeks after the transitional government ordered the ministry of interior to use “all necessary measures” to disperse the protests, has resulted in the largest death toll since the Jan. 25, 2011, uprising: More than 600 killed and 4,000 injured, and the numbers are climbing. (The Muslim Brotherhood put the death toll far higher – in the thousands.) Egypt’s interior ministry reported that 43 policemen have been killed and more than 140 wounded. On Friday, as the violence resumed, at least 17 people were killed.

In addition, more than 20 churches have been attacked around Cairo, according to the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, and banks and most businesses remained closed after the military attacks. On Thursday, the U.S. embassy issued a warning for all Americans to leave Egypt, and U.S. President Barack Obama condemned the violence and said the country was revising its position toward Egypt. “The United States strongly condemns the steps that have been taken by Egypt’s interim government and security forces,” Obama said in remarks from his vacation home in Martha’s Vineyard. “The cycle of violence needs to stop.”

The revision in the U.S. stance is more tactical than substantial, scrapping only biannual joint military exercises scheduled for September. Obama stopped short of revoking the next round of military aid, which is pending review. “Further steps we may take as necessary with respect to the U.S.-Egyptian relationship,” he noted.

Analysts say the U.S. stance since Morsi’s ouster by a military-backed popular uprising has been ambiguous and resulted in mounting anti-American sentiment, with both pro-Morsi and pro-military camps criticizing the U.S. for meddling and supporting their opponents.

Earlier this month, U.S. Senators John McCain and Lindsey Graham visited Cairo in an effort to convince the transitional government to release leading members of the Muslim Brotherhood and other “political prisoners,” which fueled resentment among the backers of the new government. “We urge a national dialogue that is inclusive of all parties, including the Muslim Brotherhood,” McCain said at a press conference in Cairo, a position that deviated from the official U.S. position by calling Morsi’s ouster a “coup.”

Adly Mansour, Egypt’s interim president, called the request an “unacceptable interference in internal politics.”

On Friday, McCain and Graham threw fuel on the fire by issuing a joint statement intended to force Obama's hand, which could also exacerbate Egyptian resentment. "We urge the Obama Administration to suspend U.S. assistance to Egypt," the Republican senators said, adding, "The events now unfolding in Egypt and the Middle East will directly impact the national security interests of the United States, and we cannot remain disengaged."

Ann Patterson, the U.S. ambassador to Egypt, has become a popular anti-hero -- a symbol of perceived U.S. support of the Muslim Brotherhood during the June 30 uprising, and an increase in activity of radical Islamists in recent weeks has meanwhile been perceived as an unprecedented threat to U.S. interests in the region, prompting the U.S. government to temporarily close embassies in the Middle East and Africa.

“I know it’s tempting inside of Egypt to blame the United States or the West or some other outside actor for what’s gone wrong,” Obama said in his remarks on Thursday. “We don’t take sides with any particular party or political figure.”

Yet as the Egyptian military’s role in the nation’s future becomes more pronounced, the U.S. faces more pressure to take a proactive stance. “There have been two large incidents of violence, largely the responsibility of the military on top of what was a coup. So precisely what does the Egyptian military have to do to put military aid in jeopardy?” asked former Assistant Secretary of State P.J. Crowley in an interview with CNN’s Erin Burnett. “I think it’s time for the Obama administration to seriously review where we are.”

Several Western countries have meanwhile recalled their ambassadors to Egypt, including France, Germany and the United Kingdom. “It was completely avoidable,” said William Hague, U.K. foreign secretary, on Al Jazeera English on Wednesday. “It [dialogue] will be so much more difficult because of events of today.”

Denmark also suspended $5.3 million in government assistance “in response to the bloody events and the very regrettable turn the development of democracy has taken.”

“Washington should, and probably will, call for a return to an elected civilian government, a rapid end to the state of emergency, and restraint in the use of force,” said Marc Lynch, a professor of political science and international affairs at George Washington University. “When that doesn't happen, it needs to suspend aid and relations until Cairo begins to take it seriously.” Some experts and politicians think Obama should cut this assistance altogether. That includes Lynch, who published an article in Foreign Policy on Thursday arguing that “it’s time for Washington to cut Egypt loose.”

As the military’s role in Egypt’s transition became more pronounced, the U.S. stance and initial reluctance to call the ouster a military “coup” outraged Morsi supporters. Gulf nations including Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Kuwait responded by pledging a total of $12 billion to Egypt’s new government since Morsi’s ouster.

"If U.S., Qatar and other outside powers stop interfering in Egypt, then we could restore peace," said Ahmed Elnaggar, the head of the economic department at Al Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies. That, he said, will enable Egypt to get its economy back on track. "Once they [the military] control these terrorist actors, we will restore our economy," he said. Otherwise, Elnaggar said U.S. military aid has little overall impact on the Egyptian economy. "It has no effect for Egyptian economy compared to our GDP," he said. In any event, aside from the suspension of maneuvers and shipment of planes, U.S. military aid for 2013 was distributed in May and so cannot be withheld.

Now, in the tense aftermath of the military attack, the Rabaa al-Adawiya mosque -- site of the largest pro-Morsi sit-ins, where protesters camped out for more than a month -- resembled a war zone, with human rights organizations and media counting hundreds of bodies wrapped in sheets and covered with ice bags. In what seemed an afterthought considering what happened on Wednesday, the ministry of interior on Thursday authorized security forces to use live ammunition to protect themselves and government buildings from pro-Morsi protesters.

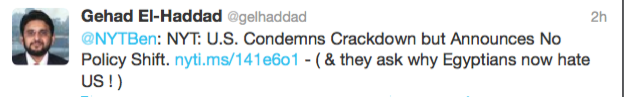

The Muslim Brotherhood remained defiant, calling for another “Day of Anger” on Friday and holding several protests across the country, including in Cairo, Alexandria and Ismaleia. "We will always be nonviolent and peaceful. We remain strong, defiant and resolved," said Muslim Brotherhood spokesman Gehad El-Haddad on his official Twitter account. "We will push until we bring down this military coup.”

“Mohamed Morsi did not have a chance to serve his term,” said Mahmoud El Naggar, a student, near the Mostafa Mahmoud square in Mohandaseen. “[General] Sisi can now arrest anyone in the streets. We are now back in time before the [Jan. 25] revolution.”

Mohamed ElBaradei, a liberal vice president and leader of the opposition, resigned on Wednesday in response to the military crackdown. "It has become too difficult to continue bearing responsibility for decisions I do not agree with and whose consequences I fear," he said in a statement. “Violence begets violence, and mark my words, the only beneficiaries of what happened are extremist groups.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.