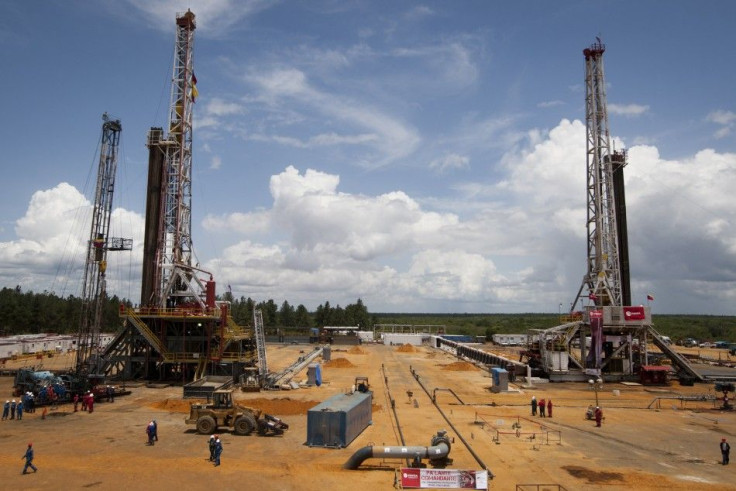

Energy Companies Seek Ways To Capture Natural Gas From North Dakota Oil Boom

The oil pumped out of the Bakken Shale fields in North Dakota brings natural gas above ground too, but the state doesn’t have the infrastructure yet to store or move the gas to processors. So about 30 percent of the natural gas rising to the North Dakota prairies is burned, emitting carbon and losing the value the methane could have had if processed into ethane, butane and other liquids.

Right now, about 1 billion cubic feet of natural gas in the state is burned into the air, Gov. Jack Dalrymple said Monday at the Bloomberg Energy 2020 conference in Washington.

“Everybody feels it’s a huge waste, to say nothing of the environmental impact,” he said. “And the companies are scrambling as fast as they can to gather up this gas and hook up the pipelines they need to move it to processing plants.”

General Electric Company (NYSE:GE), Statoil (NYSE:STO) and Ferus Natural Gas Fuels say they have an answer: their “Last Mile Fueling System.” The trio is capturing the natural gas escaping Statoil’s Bakken oil wells and stripping out propane and butane from the liquids to transport it to processors. The rest of the gas is compressed on-site in GE’s “CNG in a box” system, an 8-by-20-foot fueling station, to be used for trucks and other equipment. So far, Statoil has converted 10 rigs to run on half diesel and half natural gas. The CNG system will help power those rigs.

“Eventually, most of the flaring will be gone,”Lance Langford, vice president of Statoil’s North American Production and Development segment, said. “I think it’s a win-win for everyone.”

The natural gas replacing some of the diesel is less expensive, and the gas burns cleaner, reducing carbon pollution. “We want to replace diesel as much as possible,” Langford said. “We know we’re going to reduce emissions at the rig, but we don’t know exactly how much yet.”

It just makes good economic sense, agreed John Westerheide, general manager of unconventional resources at GE Oil & Gas.

The primary problem for the industry is that the sheer number of wells is outrunning the infrastructure needed to transport gas, but the Last Mile project could overcome this hurdle, Stewart Wilson, vice president of commercial development at Ferus, said. “We’ve just got to build out the capacity,” he said.

The companies tested the CNG system on Monday to power hydraulic fracturing equipment. In a separate collaboration, GE and Statoil are in the “early stages” of researching how to use carbon dioxide instead of water to hydraulically fracture shale rock and retrieve crude, Westerheide said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.