Ethiopia Drought Crisis: Pastoralists Threatened By El Niño, Land Grabbing, Population Growth Adopt Nontraditional Methods To Survive

Born and raised in one of the earth’s hottest and driest spots, Ethiopian herdsman Hasen Hamed perpetually moves his cattle across the northeast Afar region using traditional methods to locate green grass and drinking water, just as his father did before him. In recent years, Hamed has walked for days, only to find parched grass in customary rangelands that his ancestors had relied on to keep their herds alive. Now Hamed, 31, has just nine animals, after six died from famine this past year.

For generations, smallholder pastoralists like Hamed who live on the products of their livestock have used scouts, indigenous knowledge and “dagu,” or verbal exchange within their semi-nomadic communities, to find good pasture and water sources. But this traditional form of pastoralism is increasingly difficult to sustain in Ethiopia as rangelands dry up due to prolonged drought linked to the El Niño weather system. The sheer size of Ethiopia's agricultural population and the government's controversial land policies are also shrinking accessible grazing land, pastoral experts and researchers said. While some herders have adopted modern methods to find greener pastures, such as satellite technology, others have had to give up grazing altogether to make a steady living and feed their families.

“The bottom line is, there's just not enough grass out there to support the numbers of animals needed to provide for growing human populations,” said Layne Coppock, a professor of environment and society at Utah State University in Logan whose research includes pastoralism in Ethiopia. “The pastoralist community will drop in numbers eventually.”

The rugged, landlocked country in the Horn of Africa region is no stranger to heatwaves. But the current El Niño, the strongest on record, has caused even more severe drought in parts of Ethiopia, triggering a sharp decline in food security and massive drop in pastoral and agricultural production. As the weather system, which affects rainfall patterns and temperatures worldwide, continues to dry up pasture and water sources in Ethiopia, crop yields will fail and livestock will get leaner and sicker. Many domestic animals have already died, and more than 10 million people will face critical food shortages in the coming year, the Ethiopian government said last month.

With one of the fastest-growing populations in the world, Ethiopia is also running out of available grazing land and water points as urbanization expands into rural areas. Some 80 percent of the country’s 98.9 million inhabitants are farmers, while 15 percent are pastoralists. Ethiopia’s livestock population is the largest in Africa with tens of millions of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, camels and chickens, which surpasses the country's human population, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Herding land that pastoralists once relied on is now overgrazed or has been plowed into private farms, ranches, game parks and urban centers.

“It’s not just drought,” Coppock said. “The basic sustainability of the [pastoral] system is not there anymore.”

Ethiopia’s land-leasing policy has helped push out pastoralist populations in recent years. The government has been leasing swaths of land to investors from China, India and the Middle East for mostly agricultural projects, insisting it will create jobs, build infrastructure and reduce food insecurity. Much of this land is near key water holes and rivers, which pastoralists need to sustain their herds.

This is all legal under Ethiopia's existing land tenure system. The government officially owns all land and can lease it to individuals and businesses as it sees fit, while occupants maintain customary rights. The Ethiopian constitution states that: “Ethiopian pastoralists have the right to free land for grazing and cultivation as well as the right not to be displaced from their own lands.” But critics of the leasing policy call it "land grabbing."

Dozens of people have been killed and reportedly arrested by Ethiopian security forces in recent weeks during protests against the government’s plans to expand infrastructure development in the capital of Addis Ababa and surrounding towns in the central Oromia region. If implemented, the urban plan will affect some 2 million people around the capital and could displace farmers and herders from their ancestral fertile lands.

Felix Horne, a Horn of Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch in New York, said these demonstrations are the biggest political crisis to hit Ethiopia since the country's 2005 general elections, when thousands of people were arrested, hundreds wounded and dozens killed during a crackdown on protesters who believed the polls were rigged. He said the Ethiopian government's approach to development is the crux of the land seizure issue.

"While Ethiopia is fond of promoting its economic growth narrative, its citizens often bear the negative consequences of the government's desire to develop quickly. Displacement for development, whether for agricultural, commercial or industrial projects, is all too common," Horne said. "Individuals who question the government's economic success narrative are routinely arrested, and mistreatment in detention is common."

Anuradha Mittal, executive director of the Oakland Institute, a California-based progressive think tank, said the United States and other allies of Ethiopia should intervene and demand the government change its land policies before the situation worsens. "I think it's imperative for Western donors to start saying that things have to shift. Even for security reasons, this is a time bomb," she said.

There are other policies that put Ethiopian pastoralists at a disadvantage and make it difficult for them to profit from the livestock industry. Livestock production is key to Ethiopia's economy, but there are few legal livestock exporters due to rigid regulations and taxes that, for instance, require pastoralists to open bank accounts in order to formalize their trade.

Pastoral nomads who settle down typically must reduce the number of animals they own and grow crops and fodder to survive. Some will make a living selling milk, vegetables, charcoal or firewoood at markets. Others, particularly women, have created informal groups to pool together their savings and extend small loans to each other to start their small businesses. Nevertheless, giving up these animals — their livelihood — is not an easy decision.

“That’s a hard thing for pastoralists to do. They’re not good farmers; they don’t have the knowledge in their history and culture to do it,” said Elliot Fratkin, an anthropology professor at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, who has taught and conducted research in Ethiopia.

Hamed, the Afar pastoralist, at times has walked for five straight days to find better pasture in the arid region, which is hard hit by the prolonged drought. Hamed, who is chairman of his "kebele," which means neighborhood in his native tongue Amharic, has begun planting maize and other crops in addition to raising livestock to have enough food to feed his three wives and 13 children.

“I have a family. I’m doing what I can,” he said in a recent Skype interview from Afar’s Telalak "woreda", or district. "We are still waiting for aid."

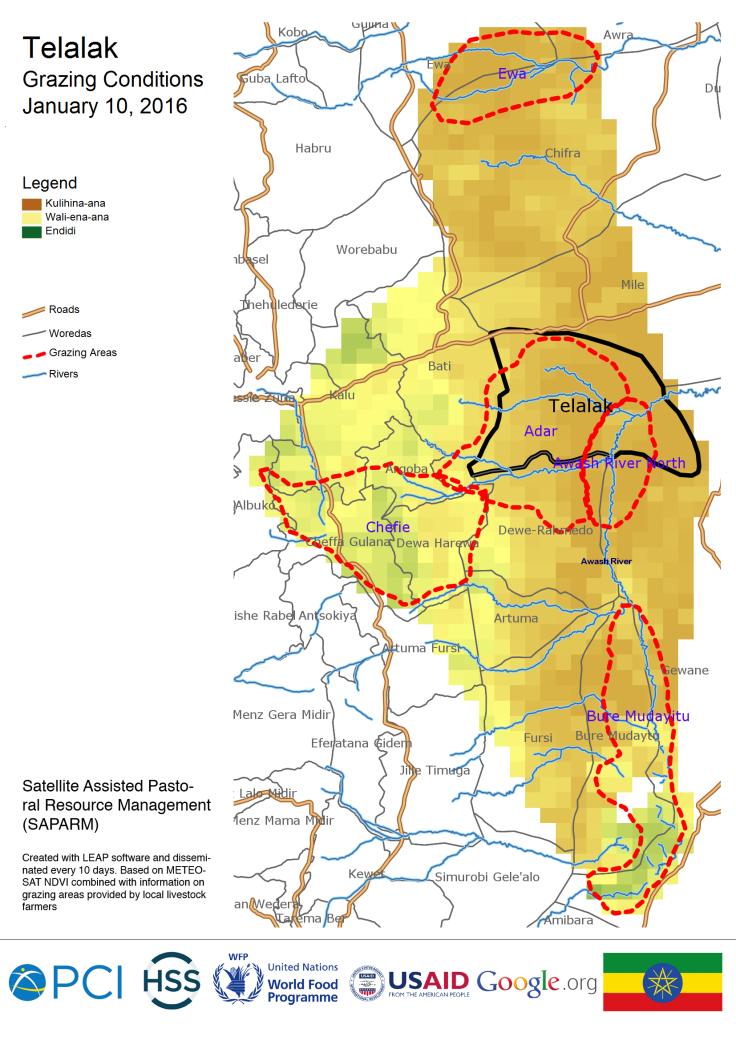

Hamed is finding promise, however, in a recent innovation that aims to help traditional pastoralists maintain their ancestral trade and nomadic lifestyle. Project Concern International, a global development organization, launched a program in 2013 funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development to provide pastoralists with maps derived from geostationary satellites to help them find greener pastures. The Satellite Assisted Pastoral Resource Management program, or SAPARM, uses a combination of infrared and direct photography to provide a measure of photosynthesis and vegetation sensitivity.

The digitized images are then overlaid on customized maps provided by pastoralist communities to show the state of vegetation within their traditional grazing grounds. Dark green represents heavy vegetation, yellow is moderate and brown means no vegetation. New maps are generated every 10 days, printed and handed out to select pastoralists who then distribute them among their communities in more than a dozen woredas in Ethiopia, as well as some areas in Tanzania. USAID recently awarded Project Concern International $1.3 million to expand the SAPARM program, and Google is also partnering on the initiative with $750,000.

“They’ll integrate this data with scouting or their indigenous knowledge. It’s not as if SAPARM replaces it, but actually enhances their other mechanisms,” said Chris Bessenecker, Project Concern International’s vice president of strategic initiatives. “If I’m going to send a scout out with a map, I now know where to send them to verify where or not there’s vegetation, whereas before it would be kind of a crapshoot.”

Hamed, who helps distribute the maps among his community, said the SAPARM program has allowed him and other traditional pastoralists to be more resilient and make better decisions in times of drought, when the wrong choice can lead to livestock deaths. So far, the project has cut livestock mortality in half for the participating communities.

“My animals are in good condition now. But I don’t know the future," he said.

Pastoral experts and researchers said the use of cell phones and the internet has significantly aided herders in other African nations and could help these populations in Ethiopia. But the country is lagging behind the rest of the continent in telecommunications due to the government's monopoly on the burgeoning industry. While mobile phone penetration averages around 70 percent in most of Africa, only 25 percent of Ethiopians owned cell phones in 2013. Just 3.7 percent of Ethiopians have internet access, compared to more than 69 percent in neighboring Kenya, according to the latest data.

"Many herders are too poor or mobile to take advantage of these new technologies. But they are catching on," said Fratkin, who is also the chair of the Commission on Nomadic Peoples, an academic working group of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences.

Pastoralists need to be better represented in government so that their voices are heard on these relevant issues. The Ethiopian government should also provide more financial support to nomadic herders, experts said, like offering insurance for livestock deaths amid prolonged drought, which would allow them to buy other food in times of dearth.

"I feel that those in power still don't fully understand the rationality of pastoralism; that in dry and uncertain environments, mobility is rational," said John Morton, professor of development anthropology in the Natural Resources Institute at the University of Greenwich in England.

That means the centuries-old practice of pastoralism will likely remain vulnerable so long as the government's policies stay the same and chronic issues like population growth and overgrazing continue to degrade resources that nomadic herders need to thrive. While these communities won't give up pastoralism entirely if they don't have to, it's a reality many may soon face.

"It's a fear pastoralists have," Fratkin said. “People are very proud of being pastoralists. It’s a very traditional form that’s been generally good for people.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.