EU Refugee Crisis: Black Sea, Arctic Routes To Europe Are More Dangerous And Longer Than Traditional Ways [MAP]

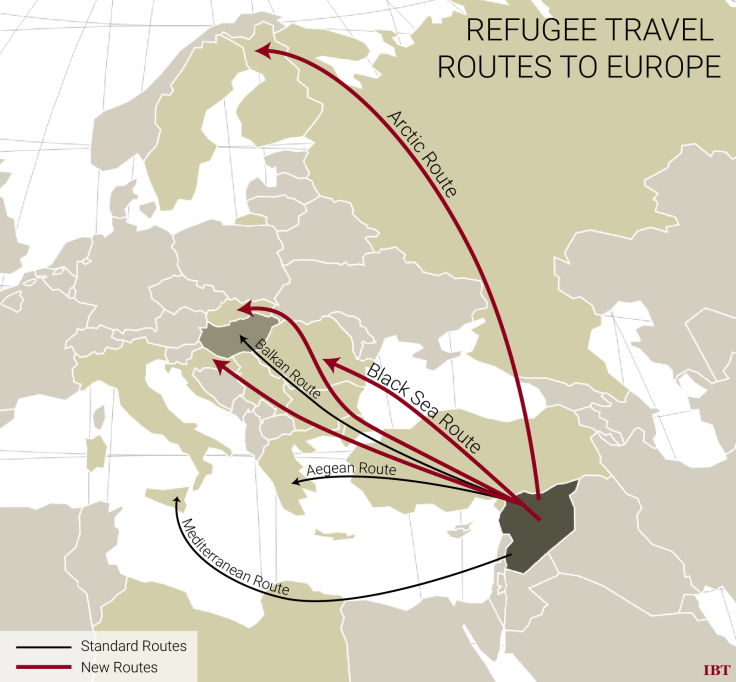

With continued discord among European Union states and Hungary’s razor-wire fence blocking the path of refugees, traditional Europe-bound routes taken over the past year have begun giving way to longer and more dangerous routes through other countries in the continent that have yet to experience an influx of people fleeing conflict in their homelands. Traveling what are known as the Arctic and Black Sea routes, refugees heading to western and northern Europe to claim asylum could soon begin undertaking dangerous crossings of the Black Sea in greater numbers. Another possibility, known as the Arctic route, is significantly more arduous.

“People will find those other routes, and even if they don’t, they will park themselves in these countries in protest,” Sanjayan Srikanthan, emergency field director of the International Rescue Committee, said. He noted that refugees were already beginning to stay in Serbia due to the blockades by neighboring Hungary.

With winter approaching, populations caught in transit could potentially be exposed to harsh conditions in Central and Eastern Europe. Srikanthan warned of the possibility of camps in Europe becoming holding zones like those in countries abutting Syria, including Lebanon.

“The big risk is that if there is a kind of pooling of people in Serbia and Macedonia,” Elizabeth Collett, director of Migration Policy Institute Europe, said. “We do have to look at the strain that that will place on those small countries.”

The war that began in 2011 in Syria has killed more than 200,000 people and displaced millions, leading refugees to resort to embarking upon dangerous journeys to reach Europe and claim asylum. Many refugees who have crossed into Europe over the past year followed routes out of Syria that led to perilous crossings spanning the Mediterranean Sea into Italy or Greece. As of Sept. 15, more than 2,800 people had died in the Mediterranean area, the International Organization for Migration reported. More than 500,000 refugees have been detected at various EU borders so far this year, according to the EU border agency Frontex.

Two other routes taken by refugees included one where they moved over land from Syria to Turkey and then into Greece, and the other followed the Balkan route through Serbia and Hungary. Fences along a part of the border in Greece and along Hungary’s full 108-mile border with Serbia have attempted to block these routes.

“It’s this desire to not claim asylum until they reach final destinations that’s causing problems,” Collett said, describing how refugees have tried to avoid registering in countries, including Hungary, instead hoping to reach more prosperous EU states that have welcomed refugees, such as Germany and Sweden.

With Croatia agreeing Wednesday to allow refugees to pass through its borders, there could soon be a shifting route through Croatia and then Slovenia to reach Austria, according to Collett.

Rumors were already spreading in Syria about the possibility of a risky but possible Black Sea route as access to older, well-trodden routes has become more difficult as governments react to the crisis by building fences, Srikanthan said. The two possible emerging routes, known as Black Sea routes, involve moving from Syria to Turkey and then going on to either Romania or Bulgaria before crossing into Slovakia. Aside from the Black Sea route, the Arctic route, a long journey from Syria to Turkey, takes travelers up through a large part of Russia in order to reach Finland or Sweden.

“The Black Sea is the least favorable option,” Srikanthan said, noting that the waters there were already cold and possible rescue attempts would need to happen at a much faster rate. “But desperate times call for desperate measures.”

As with the already traveled routes, the risks of exploitation and violence remain high, with Syrians considered high-value clients for smugglers. Srikanthan highlighted how the desire to find a job and provide a safe environment for children has driven families to attempt the dangerous journeys.

“I don’t think people will give up,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.