Evolution Of Big Brain And Small Teeth In Humans Not Linked, Study Reveals

For a long time, scientists believed that our teeth evolved in lockstep with our brains — as our brains became bigger, our teeth became progressively smaller. The reasoning was that bigger brains endowed the Homo genus with greater intelligence, allowing our ancestors to start making tools that they then used to chop down cooked food to bite-sized pieces, thus removing the need to have large chewing teeth.

This reasoning, while seemingly logical, has now been proven fallacious.

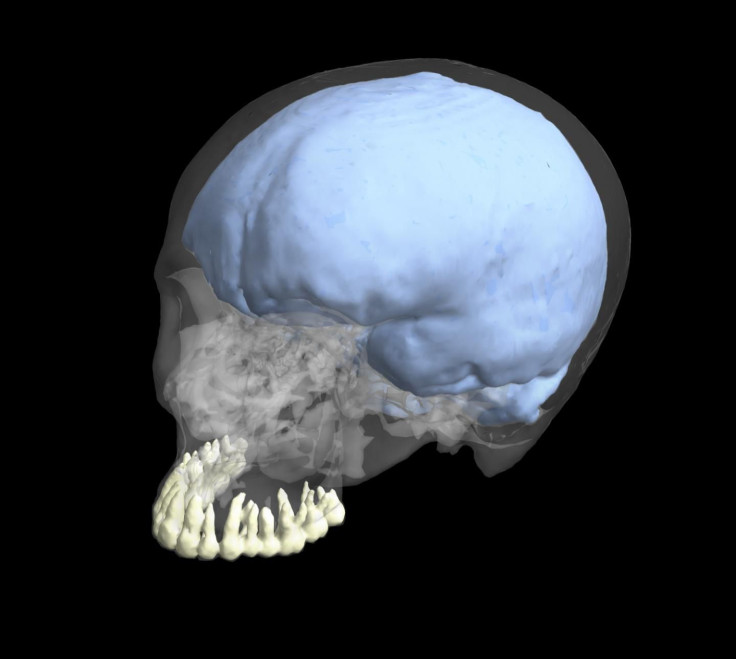

A new study, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that brain size evolution and reduction in the size of teeth within eight different species of hominins — the group of primates whose only extant species is Homo sapiens — occurred quite independently, and were therefore most likely influenced by different ecological and behavioral factors.

The study, however, does not provide answers to what influences may have affected the rates of evolution of these organs.

“The findings of the study indicate that simple causal relationships between the evolution of brain size, tool use and tooth size are unlikely to hold true when considering the complex scenarios of hominin evolution and the extended time periods during which evolutionary change has occurred,” lead author Aida Gómez-Robles, a postdoctoral scientist at the George Washington University's Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology, said in a statement.

For the purpose of the study, the researchers studied and compared the rates at which teeth and brains evolved in eight different hominin species — Australopithecus africanus and afarensis, Paranthropus robustus and boisei, and four members of the genus Homo — habilis, erectus, neanderthalensis, and sapiens.

If the belief that brains and teeth co-evolved were correct, the scientists should have seen a similar rate of evolution for both traits. However, what they observed was that while teeth — especially the molars and other post-canine teeth used for chewing — evolved at a more or less steady rate across species, the rate of increase of brain size was more heterogeneous, with the fastest ones occurring in the Homo line.

“Once something becomes conventional wisdom, in no time at all it becomes dogma,” study co-author Bernard Wood, a professor of human origins at the George Washington University, said in the statement. “The co-evolution of brains and teeth was on a fast-track to dogma status, but we caught it in the nick of time.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.