Fish Have Personalities Too, Individuals React Differently To The Same Stressful Situations

On the last track of their 1991 studio album “Nevermind,” Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain sang: “It’s okay to eat fish, ‘cause they don’t have any feelings.” While lyrics to the song “Something in the Way” are quite far removed from science, the question about whether fish have feelings or not has been up for scientific debate for a long time, with evidence increasingly suggesting that they do, in fact, have feelings.

A new research paper, published online Sunday, looks at a slightly different aspect of fish behavior, examining whether individual fish in a group have different personalities. By putting guppies in stressful situations and seeing the individuals’ reactions, the researchers concluded that fish personalities cannot be thought to exist only along a simple spectrum; instead, they have complex personalities.

For their experiment, researchers from the University of Exeter in Cornwall, United Kingdom, put a group of Trinidadian guppy (Poecilia reticulata) in different “stress contexts” and observed the behavior of individuals. These stress contexts involved an open field trial (considered “mild”), and two simulated attacks by predators (labeled “moderate”), and the coping styles of individuals were assessed beyond just “risk-prone” and “risk-averse,” according to a summary of the study.

Thomas Houslay from the university’s Centre for Ecology and Conservation (CEC), who led the study, said in a statement Sunday: “The idea of a simple spectrum is often put forward to explain the behavior of individuals in species such as the Trinidadian guppy. But our research shows that the reality is much more complex. For example, when placed into an unfamiliar environment, we found guppies have various strategies for coping with this stressful situation — many attempt to hide, others try to escape, some explore cautiously, and so on.”

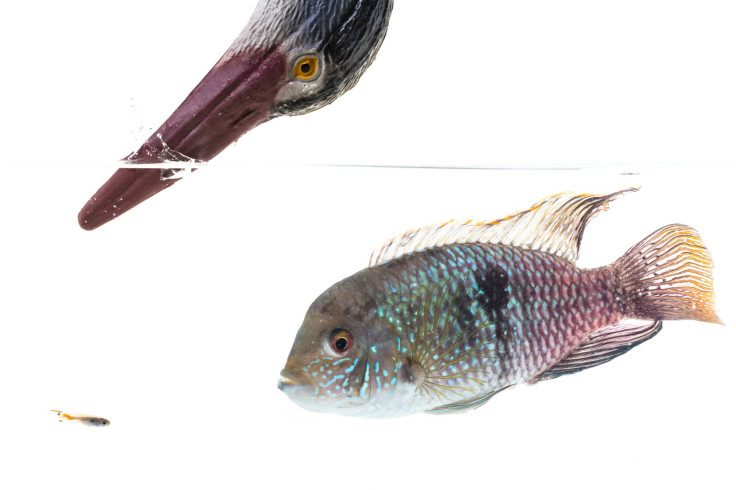

The mild stress was caused by moving the fish to an unfamiliar tank, while the higher stress situations were simulated by adding models of a predating fish — a blue acara cichlid — and a heron. Even as the guppies grew more cautious overall when faced with higher stress levels, differences in individual personalities persisted.

“The differences between them were consistent over time and in different situations. So, while the behavior of all the guppies changed depending on the situation — for example, all becoming more cautious in more stressful situations — the relative differences between individuals remained intact,” Houslay said.

“Our results provide behavioral evidence in support of the concept of coping styles, but also highlight that the full range of their underlying variation might not be readily captured analytically by a simple, single-axis paradigm, even when considering behavior alone. … even when behavioral flexibility enables populations (and individuals) to respond to environmental changes, personality structure can be strongly conserved,” the study concludes.

The open-access paper, titled “Testing the stability of behavioural coping style across stress contexts in the Trinidadian guppy,” appeared in the journal Functional Ecology.

The researchers now want to understand the cause behind the different personalities of the guppies, and the underlying genetic links that also impact other traits.

“We want to know how personality relates to other facets of life, and to what extent this is driven by genetic — rather than environmental — influences. The goal is really gaining insight into evolutionary processes, how different behavioral strategies might persist as species evolve,” Alastair Wilson, also from CEC and a co-author of the report, said in the statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.