Five Companies Responsible For A Third Of New H-1B Guest Worker Visa Approvals Last Year As Businesses Seek Cheaper Tech Work

For years, American technology companies have complained that they can’t find enough highly skilled workers while urging Washington to expand the number of temporary visas for foreign employees who bring the needed tools.

But the federal government has for nearly a decade held the line on the number of visas it issues under its so-called H-1B program, and now a new factor is making the competition for foreign tech workers even more intense: Temporary employment agencies have been flooding the government with applications for such visas, using those slots for lesser-skilled, generally lower-paying jobs, increasing the frustrations for would-be employers in pursuit of software engineers.

Five labor outsourcing companies alone accounted for 37 percent of the 65,000 new temporary work visas immigration authorities approved under the program last year, excluding the 20,000 reserved for postgraduate degree holders, according to federal immigration data analyzed by International Business Times. That has left others dependent on the visa program -- tech companies as well as thousands of other small businesses and universities seeking professional foreign guest workers -- to compete for the remaining slots.

Lost on no one is the fact that foreign workers brought to the United States under the temporary visa scheme can legally be paid less than median wages, provoking charges that the temp agencies are exploiting the program as a means of undercutting American-born workers.

“The whole process is broken,” said Neeraj Gupta, CEO of Newark, Calif.-based Systems In Motion, a three-year-old IT services provider that trains and places American college graduates in tech-support jobs. “What the visa was intended to do was to allow us to get great engineers from India, the Philippines, the Ukraine, or wherever, for our innovation economy. Instead these large outsourcing firms are bringing in lower paid testers and programmers are taking up so many of the visas.”

One of the leading originators of applications under the temporary visa program is Tata Consultancy Services Ltd. (NSE:TCS), a Mumbai-based outsourcing firm owned by the Indian conglomerate Tata Group. The company obtained approval from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services for 6,184 of the so-called H-1B visas during fiscal year 2013. Out of the top 10 companies that received the largest share of H-1B visas, only one amounts to a major tech company, Microsoft Corp. (NASDAQ:MSFT), the rest were outsourcing firms.

Tata Consultancy spokesman Benjamin Trounson told IBTimes that the company is committed to propagating local IT talent and has been offering training of U.S. students since 2009.

“TCS is among the top job creators in the US within the IT services industry and has actively recruited more than 5,000 Americans over the past three years, many of whom are working on technologies and systems that support critical client needs and help to drive America’s innovation economy,” Trounson said by email.

Critics of the H-1B guest worker visa system have long argued that it places foreign workers under unfair pressure from employers, given that they are required to leave the United States within days of losing their jobs. Under the rules drawn up by Congress, the minimum wage for H-1B workers can be as little as the so-called 17th percentile, meaning that the wage can be as low as what the 17th-lowest wage earner out of 100 in a particular job category in a specific region would earn.

That many of the temporary visas are being absorbed by lower-skilled workers willing to take lower pay is now exacerbating those tensions.

“We used to be middle class, upper-middle class,” a Union City, Calif., business management software consultant and naturalized citizen who has been looking in vain for steady work in Silicon Valley for the past four years, said. This person spoke on condition of anonymity because he is concerned about hurting his prospects for future employment. “We’re going down to lower-middle class because they’re bringing in these low-cost Indian workers with just basic tech skills by the truckload and they put them in these jobs working long hours with no overtime. I’m very emotional about this, because it’s very personal.”

Under the rules even a highly educated person with a great deal of experience coming from abroad can be paid far less than an American with comparable skills. This means companies can hire many for these guest workers at or near the lower end of the wage scale for a particular job even if their skills would typically classify as higher-paying positions.

“The way the law is written, you set the wage based on job description not based on the skills or qualifications of the worker,” Ron Hira, associate professor of public policy at Rochester Institute of Technology, said. “I know of no case where the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division has said ‘you mis-specified the skill level of this worker on your H-1B application.”

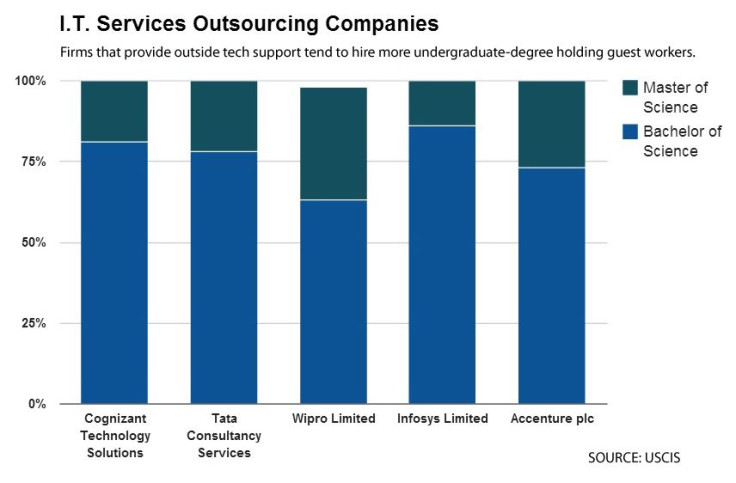

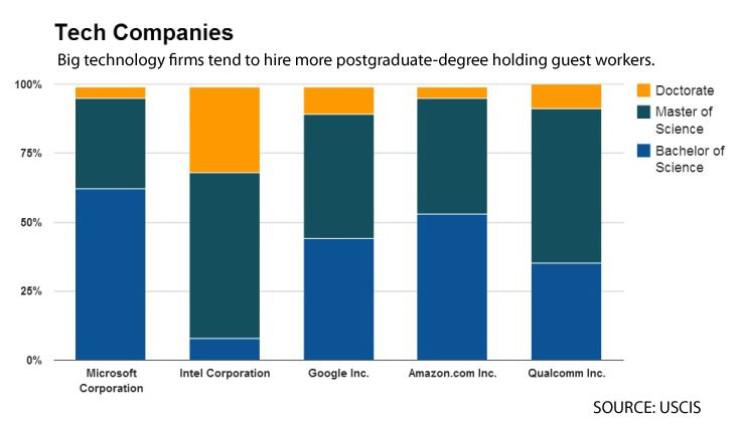

Hira recently analyzed USCIS documents from 2010 to 2012 obtained through a Freedom of Information request and found that IT outsourcing companies are more likely to bring bachelor’s degree holders to the U.S. instead of the postgraduate-degree holders the bigger players recruit and hire.

The analysis looked at the five major recruiters of guest workers in the industry -- Microsoft, Intel Corp. (NASDAQ:INTC), Google Inc. (NASDAQ:GOOGL), Amazon.com Inc. (NASDAQ:AMZN) and Qualcomm (NASDAQ:QCOM) -- and found that between 2010 and 2012, an average of 65 percent of guest workers at these companies were given green cards. The percentage of guest workers who came to the U.S. through outplacement companies was much lower, between zero and 12 percent depending on the firm. The tech companies also had significantly more holders of master’s degrees and PhDs while outsourcing companies had far greater shares of bachelor’s degree holders and mosmost no Ph.D.s. This suggests strongly that tech companies seem to be shopping for quality while outsourcing companies are focused on quantity.

Alex Nowrasteh, immigration policy analyst at the libertarian CATO Institute, offers another reason why so many H-1B visas end up in the hands a few large players: The system is so cumbersome and expensive that small businesses would rather outsource.

“The H-1B program is very highly regulated and expensive, which gives an incentive for larger firms that have big HR departments and have lawyers on staff to make those types of large requests, like Wipro and these other Indian outsourcing companies do,” Nowrasteh said.

CATO supports a complete removal of the H-1B visa cap, which has not been lifted since 2005. But he also thinks that workers who enter the country under the program should have the right to switch jobs without losing their visas. That would remove one competitive disadvantage American citizens have competing with H-1B workers, especially at entry-level positions in the industry.

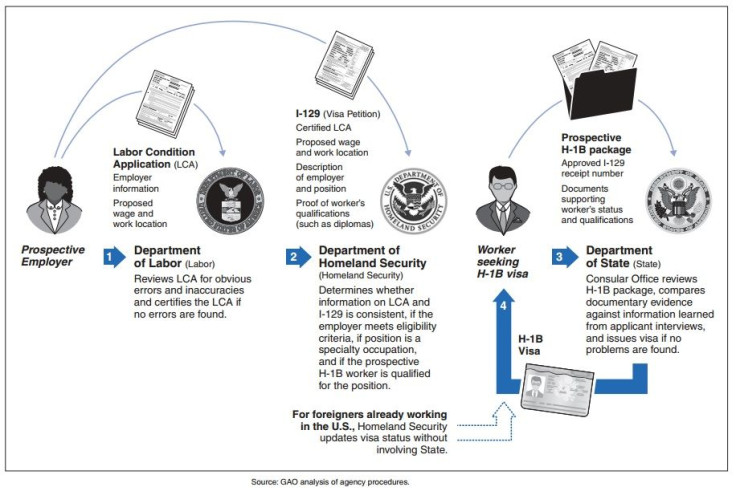

For more information about the H-1B visa program, check out this chart from the U.S. General Accounting Office. The program is overseen by three separate federal agencies: the Departments of Labor, Homeland Security (through U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services) and State. The GAO explains below how an H-1B visa makes its way through the bureaucracy.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.