Fossil Teeth Study Says Common Ancestor Of Neanderthals And Humans Belongs To 'Some African Species' [PHOTO]

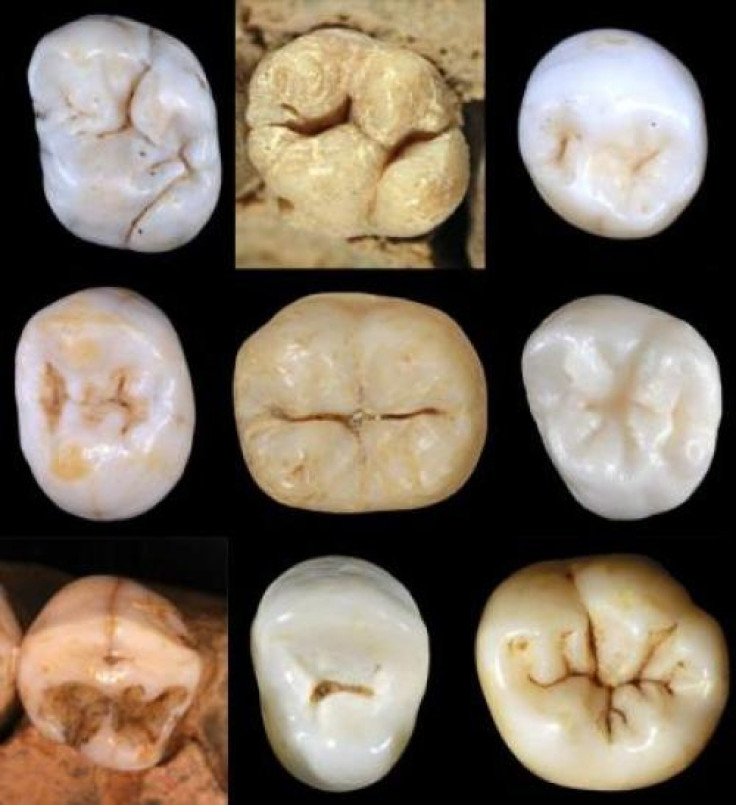

The search for a common ancestor that links modern humans to Neanderthals may find some answers in hominin teeth.

Researchers looked at qualitative patterns in Neanderthal molar fossils from Europe, Africa, Asia and modern humans and found that the two species diverged nearly 1 million years ago, much earlier than previously thought.

"Our results call attention to the strong discrepancies between molecular and paleontological estimates of the divergence time between Neanderthals and modern humans," Aida Gómez-Robles, lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral scientist at the Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology of the George Washington University, said in a statement. "These discrepancies cannot be simply ignored, but they have to be somehow reconciled."

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, focused on a collection of 1,200 premolars and molars from prehistoric humans. Researchers identified landmarks on the teeth and then reconstructed the tooth shape to model what they thought would be the tooth shape of humans’ common ancestor with Neanderthals. They concluded with high statistical confidence that the common ancestor does not belong to the species previously suggested, including Homo heidelbergensis, H. erectus and H. antecessor.

"The most likely dental shape of an ancestral species is an intermediate shape between the one observed in both daughter species," Gómez-Robles told National Geographic explaining how the tooth is a cross between H. sapiens and Neanderthals.

This possible species has yet to be identified, but it most likely lived in eastern and southern Africa 1.3 to 1.8 million years ago. “We can rule out all the European species as possible ancestors, because they are already in the line leading to Neanderthals, and we have an African species, which is the most similar one to the ancestor morphology,” Gomez-Robles told the Los Angeles Times. “So the most intuitive explanation is that some African species posterior to Homo ergastor will be the ancestor.”

DNA analysis has dated the divergence between modern humans and Neanderthals around 350,000 years ago, which suggests H. heidelbergensis may be the species in question. But the latest findings point to a divergence that took place at least 1 million years ago.

Gómez-Robles and her colleagues argue their statistical method is more reliable about determining human origins than descriptive analyses used in previous studies.

“Our primary aim is to put questions about human evolution into a testable quantitative framework and to offer an objective means to sort out apparently unsolvable debates about hominin phylogeny,” the authors wrote. “Our paper shows that no known hominin species matches the expected morphology of this common ancestor.”

While more studies on hominin fossil from Africa will paint a clearer picture of human ancestry, the study does provide some necessary details.

"The study tells us that there are still new hominin finds waiting to be made," David Polly, coauthor of the study from Indiana University said. "Fossil finds from about 1 million years ago in Africa deserve close scrutiny as the possible ancestor of Neanderthals and modern humans."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.