GDP Grows, Dow Soars While US Workers Still Chase Household Income, Wage Growth And Real Recovery

Like so many shiny presents piled under the tree, good economic news is suddenly abundant: The Dow soared above 18,000 on Tuesday for the first time ever. Third-quarter GDP growth rang up at 5 percent. Last month, unemployment registered at 5.8 percent, down from 7 percent in November 2013. And so far this year, the U.S. economy has added 2.65 million jobs -- the largest gains in payrolls since we were prepping for Y2K at the turn of the century.

These are all welcome tidings of an economic recovery now five-and-a-half-years in the making. Except for this: A lot of Americans aren't seeing that growth reflected in their incomes.

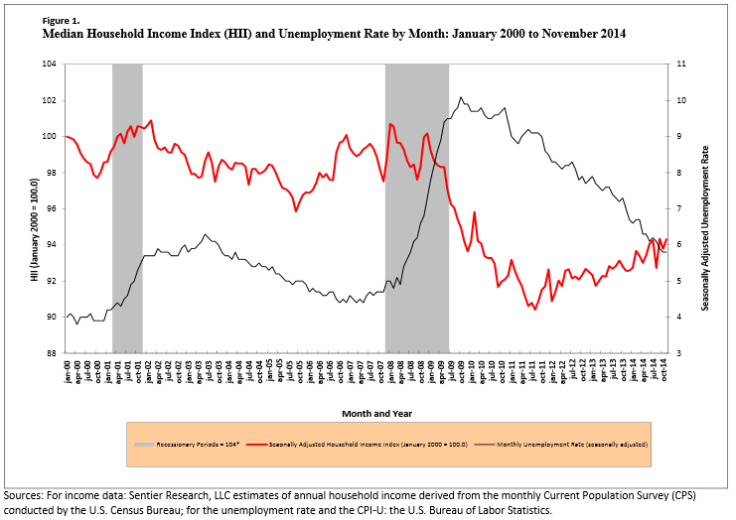

“Income is trying to claw its way back, but we're still down from where we were at the beginning of the recession, and since the beginning of the last decade,” said Sentier Research partner Gordon Green, a former chief of the governments division at the U.S. Census Bureau.

Green and his co-author, John Coder, a former head of the income statistics branch at the Census Bureau, track how median annual household income changes each month. At the beginning of the recession, in December 2007, households pulled in a median of $56,447 per year (in inflation-adjusted, November 2014 dollars). That fell to $55,434 by June 2009 -- technically the beginning of the recovery -- and then it kept falling.

“Income did not bottom out until August 2011,” said Green, when the median figure finally came to rest at $51,652.

Since then, income has risen 4.3 percent as of November 2014, to $53,880 (according to Sentier's data released Tuesday, based on an analysis of the monthly Current Population Survey). Still, that's 4.5 percent lower than in December 2007, and 5.7 percent lower than in January 2000, when the median annual household income was $57,128. "The bright spot is we're starting to come up from the August 2011 low point," Green said. "We just have not fully recovered yet." (Take a look at the chart.)

One reason for that: flat wages. Whereas "household income" encompasses sources such as Social Security payments and unemployment benefits, hourly wages tell us how well the economy is converting growth in productivity into "overall rising incomes for the vast majority," said Josh Bivens, research and policy director at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute (EPI).

So how's that going for most people? "Pretty bad," Bivens said. "In the short run, since the recovery began in 2009, the bottom 90 percent have essentially gone nowhere."

Bivens' colleague, Elise Gould, crunched the numbers on EPI's blog last week. In November, private sector workers earned an hourly average of $24.66 in real (inflation-adjusted) wages. "These wages are no better than we saw in the year ending November 2009 or November 2010, where average hourly earnings were $24.60 and $24.61, respectively," she wrote. (Check out the chart.)

Nor have the majority of workers fared much better since the late 1970s, said Bivens. In a sign of rising income inequality, "wages for the bottom 70 percent since 1979 have either grown trivially" -- about 0.2 percent, at most -- "or less than that," he said.

The stagnation, Bivens argues, reflects policy decisions that have shifted bargaining power away from low- and moderate-wage workers. For example, the share of workers covered by a union contract has been cut in half over the last three decades, down from 26.5 percent in 1975, to 12.4 percent in 2013.

The federal minimum wage, at $7.25 an hour, isn't worth nearly what it used to be, either. Adjusted for inflation, the value "is about 25 percent lower than it was in 1968," Bivens said. "That is during a period when productivity has grown 80 percent," he added.

Jobs in low-paying service sectors like retail and food have also become more of the norm in the postrecession economy. As Morgan Stanley analysts noted in September, "Since the labor market recovery began in early 2010, we estimate that roughly 65 percent of net new jobs created have been concentrated in low wage-paying industries."

As of 2012, the U.S. outranked every other developed country with the highest share of low-paying jobs, the same Morgan Stanley paper said, citing the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. By contrast, "In 2001, the U.S. ranked fifth," wrote analysts Ellen Zentner and Paul Campbell.

Federal Reserve policymakers hold the key to a near-term bump in pay, Bivens argues: They should prioritize keeping unemployment low over keeping inflation low. That's because low unemployment translates into a bigger bargaining chip for workers further down the income scale.

"In order to get a raise from your boss, you need to convince them that it would be hard to replace you if you quit," Bivens said. Case in point: The best period of wage growth in the last 25 years occurred during the late 1990s, when pay rose about 2 percent and unemployment averaged about 4 percent (between 1999 and 2000).

At one level, the failure of wages to keep up with the country's economic output evidences a fundamental breakdown, Bivens said: "It means the living standard of a great majority of American workers is going to lag overall economic growth."

"That, to me, is the definition of a failing economy," he added.

More broadly, wage stagnation, intertwined with income inequality, might make it increasingly difficult to generate economic demand going forward. As Morgan Stanley analsysts Zenter and Campbell pointed out some months ago, "despite the roughly $25 trillion increase in wealth since the recovery from the financial crisis began, consumer spending" -- the largest share of the U.S. economy -- "remains anemic."

"To lift all boats," they wrote, "further increases in residential wealth and accelerating wage growth are needed."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.